Tatas face costly divorce settlement with century-old partner

It is turning out to be the biggest high-voltage divorce in the annals of Indian corporate history. The Shapoorji Pallonji Group, a relatively small but longtime partner of Indian oldest industrial conglomerate, the Tatas, brought the simmering four-year conflict to a turning point on September 22 by initiating proceedings to break the ties.

It is turning out to be the biggest high-voltage divorce in the annals of Indian corporate history. The Shapoorji Pallonji Group, a relatively small but longtime partner of Indian oldest industrial conglomerate, the Tatas, brought the simmering four-year conflict to a turning point on September 22 by initiating proceedings to break the ties.

But if the past is any guide, the path towards a breakup is unlikely to be smooth, amicable or free of rancour. This is largely due to the uniquely peculiar ownership structure of Tata Sons, the Group’s holding company, which controls the more than 100 listed and unlisted entities in the sprawling empire.

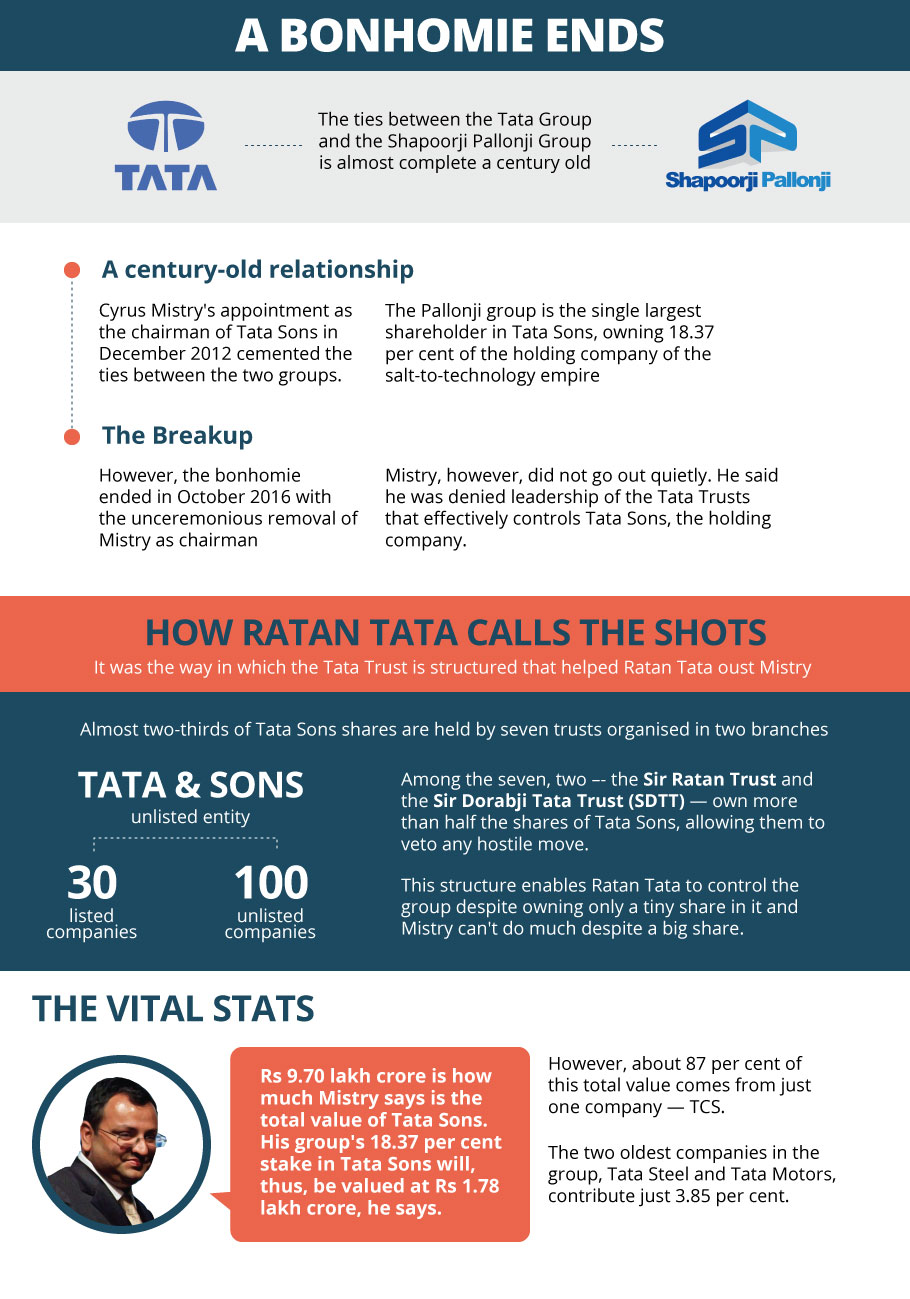

Ever since Cyrus Mistry, the scion of the Pallonji clan who chaired Tata Sons for four years before Ratan Tata, his predecessor at the helm, engineered his sudden eviction in October 2016, the partnership between the two Parsi business groups has been inexorably heading towards a rupture.

Related News: As Mistrys seek to sell Tata stakes, valuation emerges as the key challenge

The ties between the two illustrious groups began almost a century ago when Framroze Eduljee Dinshaw’s private company, which had business interests in Karachi as well as in what was then known as Bombay lent the then princely sum of Rs 2 crore to the Tatas to tide over their financial problems at Tata Steel — then just two decades in existence.

The inability of the Tatas to repay the loans resulted in an agreement that allowed Dinshaw’s company to be paid a fraction of Tata Sons’ commissions. This arrangement changed hands when Dinshaw sold a part of his company to Cyrus Mistry’s grandfather, Shapoorji Pallonji Mistry in 1928.

The inability of the Tatas to repay the loans resulted in an agreement that allowed Dinshaw’s company to be paid a fraction of Tata Sons’ commissions. This arrangement changed hands when Dinshaw sold a part of his company to Cyrus Mistry’s grandfather, Shapoorji Pallonji Mistry in 1928.

Later, in the 1950s, Dinshaw sold a majority stake in his company to Pallonji, and then in the late 1970s, he sold all his remaining stake to the construction tycoon. That is when Pallonji’s investments were routed through the group company Cyrus Investments.

Apart from this, since the mid-1960s, the Pallonji group had also acquired shares of the Tatas’ holding company, signifying the close ties between the magnates of the construction business and the Tatas, which was then led by its most well-known modern face, J R D Tata. Today, the Pallonji group is the single largest shareholder in Tata Sons, owning 18.37 per cent of the holding company.

The war in the boardroom

This long-standing bonhomie between the two groups was cemented when Cyrus Mistry was appointed Chairman of Tata Sons in December 2012 after serving as an understudy to Ratan Tata for a short period. However, the apparent conviviality soon withered in what proved to be a full scale war.

When Mistry was appointed at the helm, the group’s stability was in danger because under Ratan Tata, the empire had recklessly bet on aggressive investments in pursuit of expansion and international acquisition. Basically, Mistry accused Ratan Tata of having indulged in reckless overreach in attempting a quick scaling up of the Tata empire without paying attention to the lurking risks. The target of Mistry’s attacks were focused on three sets of investments by the Tatas.

Related News: Ratan Tata shares his journey ‘from shop floor to Chairman’s seat’

The first related to Tata’s oldest and most prestigious industrial enterprise, Tata Steel. The acquisition of Corus, one of the global steel majors located in Europe, by Tata Steel for a consideration of $8.1 billion in late 2006 (the deal was consummated the following year), was cited as a white elephant. By the time Mistry was in the saddle, the burden of the acquisition started to tell on the fortunes of the Tata Group. The heavy debts and the problems at Corus’ plants in the UK made the burden heavier. Later events proved Mistry’s misgivings right as the Tata themselves started to look for buyers of the assets that had proved to be such a poor bet.

But this was not all. Tata Motors’ decision to buy Jaguar Landrover (JLR), and its decision to bet heavily on the Tata Nano small car project were both seen by Mistry as costly investments. The acquisition of JLR, the maker of luxury cars, two years after the Corus deal, for $2.3 billion was also viewed as reckless by Mistry. He also attacked Ratan Tata’s pet project, the Tata Nano, which, when launched the same year as the JLR deal, was touted as a revolutionary product tailored for the Indian urban lower middle class market. Although the JLR project initially appeared to be a success, the thin sliver of demand in the upmarket segment that it addressed could not insulate its owners durably from the recessionary winds that has swept the global economy in the last decade.

Mistry was also critical of the manner in which the Tatas doggedly continued pouring good money after bad into Tata Teleservices, the group’s telecom venture that spectacularly failed to make the most of the telecom boom in India since the 1990s.

Things came to a head in October 2016 when Ratan Tata initiated the move to summarily dismiss Cyrus Mistry from the helm and stepped in as the interim Chairman of Tata Sons. Mistry refused to simply walk away quietly. He retaliated by alleging that his summary dismissal was “unique in the annals of corporate history.” Central to his counterattack was his allegation that he, unlike his predecessors at the helm of the Tata empire, was denied leadership of the Tata Trusts that effectively controls Tata Sons, the holding company. This unwritten rule was only breached between 1932 and 1938 when Nowroji Saklatwala chaired the holding company.

The unique structure of the Tata Group

Understanding the role of these trusts and how they exercise control over the gigantic conglomerate is central to how things may unravel when Mistry walks away from the longstanding partnership with the Tatas for good. In fact, the peculiar manner in which the trusts are structured — and how they are controlled by the Tatas — is what made it possible for Ratan Tata to summarily oust Mistry in 2016.

The ownership structure of the sprawling Tata empire is unique. Unlike many Indian family-owned groups, it is not structured like an enterprise in which individual members of the family together hold a controlling stake in the company. But neither is it styled like a Western-style corporate group. Interestingly, while it cannot by any stretch of the imagination be termed a family owned group, it has always been headed by a Parsi. In fact, the Tata Group’s ownership structure resembles more closely a Japanese keiretsu or a Korean chaebol.

Related News: Valli Arunachalam denied board seat in Murugappa Group, here’s why

Tata Sons, which presides over a web of more than 30 listed companies and close to 100 unlisted entities, is itself unlisted in the share markets. A network of seven trusts, organised in two branches, hold almost two-thirds of the Tata Sons shares.

Among the trusts, the two largest — and also the oldest –- the Sir Ratan Trust, established in 1919, and the Sir Dorabji Tata Trust (SDTT), set up in 1932, own more than half the shares of Tata Sons. The trusts not only own the majority of shares but can also veto any hostile move inimical to the core controlling interests in the Tata empire.

This peculiar structure of one of India’s shining icons of capitalist enterprise is what makes for remarkable irony. While Ratan Tata owns only a tiny fraction of the holding company, he is able to call the shots, while Cyrus Mistry, despite controlling the largest block of shares in Tata Sons, cannot have his way.

A messy corporate divorce settlement

Ever since 2016, Mistry has been doggedly fighting the Tatas at various legal fora — in the National Company Law Tribunals and in the courts — alleging mismanagement as well as recklessly abandoning corporate governance norms.

It appears that Mistry has played his cards very well. He forced the Tatas to react by threatening to pledge his group’s 18.37 per cent stake in Tata Sons to pay off dues that have accumulated since the Covid crisis.

It is extremely far-fetched to imagine that he or his group would be forced to pledge the entire stake to pay off an estimated Rs 30,000 crore that the group apparently owes to creditors. After all, even by its own reckoning, which it presented in Supreme Court, the value of its shares would amount to a whopping Rs 1.78 lakh crore. To comprehend that figure in a comparable context, the entire GST shortfall of all the states put together in the current financial year is estimated to be about Rs. 2.35 lakh crore. Mistry’s implication that he would need to liquidate his entire stake to pay off his loans is like a man selling off his house to buy a shirt.

But the problems for the Tatas lie in figuring out how to let Mistry encash the value of his shares. According to the Mistrys, the value of all listed entities is about Rs 7.80 lakh crore, and those of the unlisted entities (such as Tata Capital, Tata AIG and many others) is valued at Rs 0.44 lakh crore. In addition, the Mistrys have valued the Tata brand, for which Tata Sons collects a payment from companies in the stable, at Rs 1.46 lakh crore. The total value of Tata Sons is thus placed at Rs 9.70 lakh crore. The Mistry group concludes that its 18.37 per cent stake is, thus, valued at Rs 1.78 lakh crore.

Related News: COVID highlights the urgent need to reimagine capitalism

It is not as if the Tatas do not have the money to pay Mistry. It can borrow money to pay Mistry or it can choose to liquidate a part of Tata Sons holdings in group companies to raise funds. But there are serious problems whichever course it adopts. Borrowing to fund this kind of massive amount would strain its finances, especially when it is trying to reduce debts.

TCS, the golden goose

Liquidating stakes in the companies Tata Sons holds is fraught with even greater risks. This, in part arises from the relative value of the companies in the Tata stable. For instance, Tata Consultancy Services (TCS) accounts for a whopping 87 per cent of the value of all of Tata Sons’ holdings in listed companies of the group. In comparison, the value of two of its oldest prime jewels, Tata Steel and Tata Motors, accounts for just 3.85 per cent.

On the surface, it may appear that the Tatas can easily liquidate a portion of its holdings in its biggest cash cow TCS to pay Mistry. But this is not as simple as it appears. For one, while the value of all free floating TCS shares is valued (based on market capitalisation) at about Rs 2 50 lakh crore, the value of the effective stake of the Mistry Group’s holdings of these shares is almost 50 per cent of that for the freely floating shares. If Tata Sons were to shed holdings of this magnitude in a fell swoop, it would result in the immediate collapse of the share in the stock market.

Finding another investor as a replacement for Mistry is fraught with serious risks, something the Tatas have assiduously avoided throughout its history. After all, this strategy has protected it from hostile takeover attempts.

All this points to the fact that Mistry’s litany of complaints against the sages of the Tata empire may have a kernel of truth: that within the lopsided nature of the vast conglomerate hides great frailty. The Tatas can choose to see Mistry’s challenge as a hostile parting of a longtime friend. But it may perhaps be wiser to see it as a wake-up call from the one-time friend.