How Amarinder Singh went from Punjab’s Captain to Captain Cooked

To many outside Punjab, Singh’s ouster seemed like yet another self-goal by the Congress. However, the events that unfolded in Chandigarh on Saturday had been in the making a long time

Unlike the BJP, which swiftly executed four coups against its chief ministers in three states over the past six months – the most recent in Gujarat – the option of starting afresh without any hiccups was never available to the Congress party in Punjab. Hamstrung by continuing internal turmoil that repeatedly spilled out in public, a leadership troika torn between being status quo-ist and disruptive, and debilitated by worsening electoral atrophy, the Congress steadily sunk into a morass of its own making in Punjab for nearly three years. It did precious little while disaffection grew among its MLAs against Amarinder Singh.

On Saturday, pushed into a corner by his own colleagues, indeed many who were, not long ago, part of his coterie of trusted aides, Singh resigned as chief minister, just four months ahead of the assembly polls that are due in his state. To many outside Punjab, particularly a section of journalists and political observers comfortably ensconced in Delhi’s newsrooms, Singh’s ouster seemed like yet another self-goal by the Congress in the lone state out of five – the others being UP, Uttarakhand, Goa and Manipur – where it had a clear chance of victory in the polls scheduled for early 2022. However, the events that unfolded in Chandigarh on Saturday had been in the making a long time. The Congress’s fault – as is almost always the case in such matters – was in not acting sooner to facilitate a change of guard, no matter how ugly Singh’s expected protestations were; as they have now evidently been.

Also read: Can Ghulam Nabi Azad win the RS seat from TN? Plot thickens

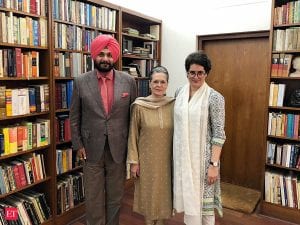

The vastly contradicting perceptions, arguably, were because of the two key dramatis personae in this Punjabi epic. Captain Amarinder Singh, a two-term chief minister, an army veteran of the 1965 Indo-Pak war, erstwhile Maharaja of Patiala, an Akali-turned-Congressman who was former prime minister Rajiv Gandhi’s senior in school and continued to share a warm, personal rapport with interim Congress chief Sonia Gandhi – and one of only three serving Congress CMs in the country. The other was the loquacious Navjot Singh Sidhu, a former cricketer, TV host and a man known for his outsized political ambitions and fickle ideology, who as a BJP leader before 2014 was an acerbic critic of the Gandhi family – many still credit him for coining the term ‘Pappu’ for Rahul Gandhi – and of former prime minister Dr Manmohan Singh. Soon after joining the Congress in 2017 and becoming an MLA and then a minister in Singh’s cabinet, Sidhu wanted to be elevated to the chief minister’s chair without any delay.

The temptation among many to paint the 79-year-old Singh as the Congress loyalist and proud nationalist, betrayed by his party’s first family only to appease the 57-year-old tantrum-throwing Sidhu is, thus, understandable. However, contrary to what has been projected simply as a unidimensional script of a factional war between the two equally headstrong Jat Sikh leaders from Patiala, the Congress’s Punjab drama had multiple sub-plots and an ensemble cast that stayed in the shadows, but contributed in no small measure to the story that has played out thus far. The final Act of this play is still unscripted though Singh, after tendering his resignation, has dropped enough hints of the direction in which he wishes to turn the story. The Congress, despite having a long time to mull over the Punjab succession plan, is still trying to find a suitable candidate who can hold the CM’s chair all for four months.

Podcast: Why BJP picked ‘rookie’ Bhupendra Patel as Gujarat CM

Singh’s problem, say sources in the Congress, wasn’t just Sidhu’s rebellion, even if the former cricketer, as is his wont, wishes to project himself as the man who brought the Maharaja to heel. A key driver of the machinations that have been playing out in Punjab was the lack of trust and camaraderie between Singh and the two Nehru-Gandhi siblings – Rahul Gandhi and Priyanka Gandhi Vadra. Ahead of the 2017 Punjab assembly polls, Singh had virtually forced Rahul into projecting him as the party’s chief ministerial candidate using the threat of quitting the party. The Congress, at the time, was in no position to let Singh walk out of its fold – a situation that the Patiala royal’s detractors say has changed five years on. Back in 2017, Singh, of course, delivered on his promise to Sonia Gandhi of winning Punjab for the Congress; a fact Sidhu never fails to dispute while taking part of the credit for that victory on grounds that his fiery oratory and popularity among the Punjabi youth also contributed greatly to the win.

However, in less than a year since the 2017 victory things had begun to go downhill for Singh. It was a slide that only got steeper with every passing year while the Gandhis, unable to arrest the party’s steady decline nationally and dissensions within the Congress, sat in Delhi in the hope that Singh will, sooner or later, win over his detractors. That clearly did not happen. “We came to power riding on a few key manifesto promises – prompt investigation and action in the 2015 sacrilege cases, crackdown on the drug mafia that was patronised in the state by the Akalis and their leader Bikram Majithia, farm loan waiver and sweeping agricultural reforms. For a better part of his term, Singh simply did not do anything on these issues and the people began getting agitated,” says a senior Punjab Congress MLA.

It was the 2015 sacrilege incident – pages of the Guru Granth Sahib were torn and burnt by some anti-social elements and in the protests these incidents evoked among common people, the police opened fire; public anger was targeted at the then Akali Dal-BJP government – that had contributed significantly to the Congress’s 2017 victory. Nearly five years later, Sidhu used the Punjab police’s shoddy investigation into the cases and the government’s alleged inaction to up the ante against his party’s CM.

Also read: Inside story: Why Rupani had to resign as Gujarat CM, and who comes next

Congress sources say Singh cleverly misled the party high command about his continuing popularity across Punjab by pointing at a series of electoral wins – eight of the state’s 13 Lok Sabha seats in 2019 and practically all major local body elections since 2017 – that his party registered under his leadership. In many of these elections, it was not simply Singh’s popularity that the Congress benefitted from but, to a greater extent, the lack of an effective opposition and various local factors that shaped the victories.

Anti-incumbency against Singh’s government had been growing, say his rivals within the Congress, adding that countless attempts by party MLAs to seek the Gandhi family’s intervention in Punjab affairs fell on deaf years. As his rivals within the party grew, Singh, say sources, began appropriating all power in the Chief Minister’s Office, running the government through a coterie of bureaucrats who would often ride roughshod over elected representatives – including ministers in Singh’s cabinet.

“A majority of our MLAs were unhappy that they could not get various works done in their constituency… even ministers had similar complaints. If senior ministers like Tript Rajinder Singh Bajwa and Sukhjinder Randhawa, who had firmly stood behind Captain when we were out of power and his stock with the high command was ebbing, are today baying for his blood, it is for the Captain to introspect how things came to such a pass,” says a former Union minister from Punjab.

It is reasonable to ask how, if so much was wrong in Punjab, was Singh able to present an image of a man in control of things. A senior party MP from the state says, “The Covid pandemic and the farmer protests were a big blessing for Singh because suddenly the anger of the people was directed against the Centre… in Punjab, farmers were angry against our government because of inflated power bills, power outages and our failure to grant the farm loan waiver we had promised in 2017, but when the Centre passed the three controversial farm laws, the focus shifted entirely to the farmer agitation against the BJP and also scorched the Akali Dal (the Congress’s key rival in Punjab), which was part of the NDA coalition when these laws were first brought.”

But as the Punjab polls drew closer, the anger among the state’s peasantry also turned to unfulfilled promises of Singh’s government. This, along with other unrealised poll promises and shoddy implementation of government schemes, was milked by Sidhu and the steadily growing anti-CM lobby within Punjab Congress. Ever since he quit the Punjab cabinet in 2019, Sidhu had kept quiet. It is no co-incidence that he suddenly surfaced four months ago and began talking about Singh’s unfulfilled promises. Sidhu utilised this time to also reach out to other Congress MLAs who were unhappy with Singh’s style of functioning. It was then that the high command stepped in and formed the three-member committee under Mallikarjun Kharge to find a solution. When Priyanka Gandhi put her weight behind Sidhu, Singh’s fate was sealed. Despite Singh’s strong protests, Sidhu was made the Punjab Congress chief on July 18 and the CM was also denied his pick of the four working presidents that were simultaneously appointed.

Sources say that the Congress high command had made up its mind to brazen out any dissensions from the pro-Singh camp, which was shrinking within the party’s 80-member strong legislative bloc in the state’s 117-member assembly, but still included a bulk of the party’s members of Parliament. Singh tried to hold on; he reached out to his old rival in the state Congress – party MP Partap Singh Bajwa – and other MPs like Ravneet Bittu (both Bajwa and Bittu are close aides of Rahul Gandhi), as well as Manish Tewari (part of the Congress’s infamous G-23) who threw their weight behind the CM. Singh had earlier also roped in political strategist Prashant Kishor as his principal advisor. Kishor did try to patch things between Singh, Sidhu and other dissenters but realised soon that this was a lost cause.

Also read: The politics behind rise of BJP’s ‘dark horse’ – Bhupendra Patel

After helping Mamata and Stalin win the Bengal and Tamil Nadu polls earlier this year, Kishor also began his own discussions for a possible entry into the Congress while distancing himself from Singh. Congress sources say it was around this time that, in his informal assessment of the political scenario in Punjab, Kishor told the Gandhis that their party may not fare as well in the upcoming assembly polls as Singh was projecting. The Congress high command decided to commission independent surveys to gauge the mood of Punjab through private agencies. The findings were devastating. “The surveys suggested that a Singh-led Congress in the assembly polls may not win in light of heavy anti-incumbency; Kishor too quit as Singh’s advisor… While Sidhu definitely played a role in getting Singh’s rivals to up the ante, the final decision to ease out the CM was taken by the high command based on independent inputs,” a leader privy to the recent developments says.

While Singh maintains that it was he who called up Sonia Gandhi on Saturday morning to inform her of his decision to resign, sources say the central leadership had made it clear to the CM that he could either resign on his own or suffer the embarrassment of having the Congress Legislative Party pass a resolution against his leadership. Harish Rawat, the party’s in-charge for Punjab, along with two other senior leaders had already spoken to all Congress MLAs individually by the time Saturday’s CLP meeting was convened and told them that a change of guard was imminent. Soon most remaining Singh loyalists jumped ship too, choosing their political future instead of gambling it for an out-of-favour satrap.

At the CLP meeting where 78 of the party’s 80 MLAs turned up (Singh and the Punjab assembly Speaker Rana K.P. Singh), the Congress tried to give a graceful exit to the CM by passing a resolution – the only solace Sonia Gandhi wished to extend to her former confidante – praising Singh’s leadership and urging him for continued guidance. Singh, who had largely kept his counsel through months of turmoil, however, had clearly had enough. Soon after giving his resignation to the governor, Singh appeared in a series of television interviews lashing out at the humiliation he had suffered and making it clear that he would never support Sidhu as the next CM. From insinuating about Sidhu being “mixed up with Pakistan” to playing the nationalist card by flaunting his regimental turban from his days in the army and raising the Pakistan bogey, the bitter CM was now singing a tune that many who were still sympathetic towards him until then saw as starkly similar to the BJP’s rhetoric.

For now, Singh has maintained that all his political options are open though he continues to be in the Congress. Speculations ranging from him floating a party to those of joining the BJP have swirled wild since Singh’s televised interviews. Meanwhile, the Congress high command, which allowed the Punjab crisis to simmer for over three years, is now conflicted over who it must hand the reins of the poll-bound state to. Singh’s exit surely resembles that of a Maharaja defeated and humiliated in battle but there are no victors in the Punjab Congress, just yet.