Facial Recognition Technology: Storm in the West, calm in India

Even as privacy advocates in India have flagged similar concerns, more and more states have been using advanced facial recognition technologies, virtually bordering on mass surveillance, in the name of modernising their police departments.

As a fallout of the “Black Lives Matter” movement and growing public anger against police brutality, the global technology giants Microsoft, Amazon, and IBM have decided not to sell their facial recognition technology to the police departments in the United States.

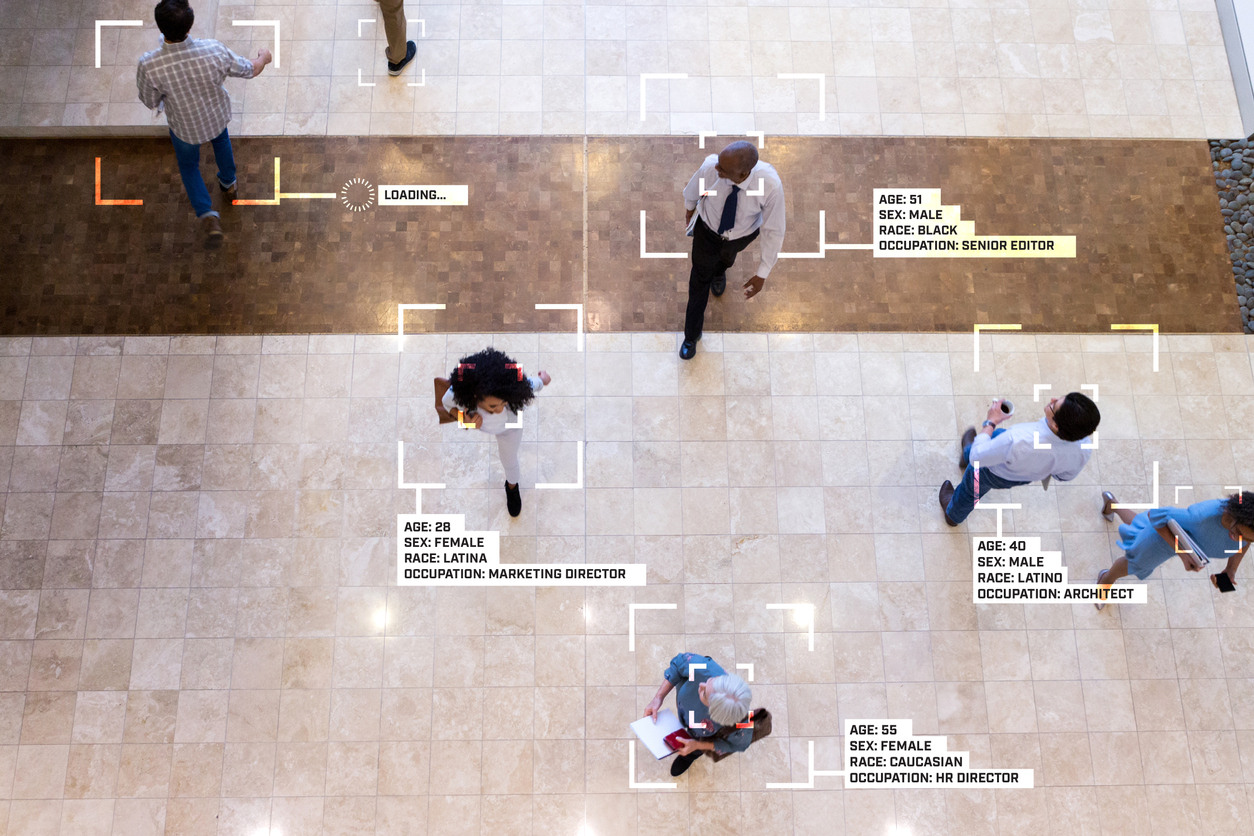

The announcements came in the backdrop of growing concerns in the US, UK, and some European countries over the use of this technology for mass surveillance and racial profiling, undermining basic human rights and freedoms. The protests, following the death of George Floyd, have focused attention on racial injustice in America and how the police use technology to track people.

In sharp contrast to the stiff public resistance in the western world, the adoption of such intrusive technologies is going on at a rapid pace across India without any semblance of pushback from the public.

Even as privacy advocates in India have flagged similar concerns, more and more states have been using advanced facial recognition technologies, virtually bordering on mass surveillance, in the name of modernising their police departments.

Related news: Microsoft joins Amazon, IBM in pausing face scan tech for police

Several states, including Telangana, Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Delhi, and Punjab, are already using the facial recognition system in police departments as part of modernisation plans, ostensibly to catch criminals and find missing children.

“Why do you think it will be misused? In fact, the FRS has been helping us to solve important criminal cases. To say that it amounts to mass surveillance is a misnomer,” a senior Telangana police official told The Federal.

The technology allows the police to match photos of subjects against a set of large databases.

Telangana has built a state-of-the art surveillance system which brings together citizen records from voter ID databases, driving licences, vehicle registration, ration cards, and other social schemes.

The Hyderabad police uses a mobile app called the TS COP. Using a suspect’s name and a photo clicked by the police, the app can trawl several state databases — voter IDs or ration cards, for instance — and check one’s ID and police records.

No legal basis

The video surveillance and tracking of suspects has no legal basis. However, this has not deterred the authorities from going ahead with surveillance activities.

“None of the laws in India, including the Information Technology Act 2000, addresses the issue of violation of privacy by police or any other private agency with the use of facial recognition technology. Nor are there any rules to regulate the use of such database of personal information of citizens — without their consent,” says Ch Prashant, a Hyderabad-based advocate and privacy activist.

“Quite often, the police end up using these technological tools to harass the critics and dissident voices,” cautioned N Venugopal Rao, a senior journalist-writer.

Related news: Experts flag privacy concerns as Telangana uses facial recognition for polls

The Telangana police, for instance, are using Artificial Intelligence (AI) based surveillance system to check whether people are using face masks. The AI-based system, embedded through CCTV cameras, will enable the police to detect the violations.

“Such kind of mass surveillance violates the citizens’ privacy which is a fundamental right. Under what laws such surveillance is being undertaken?” wondered SQ Masood, a city-based social activist.

New central legislation

The privacy activists have also raised objections over a new legislation proposed by the Union Home Ministry that seeks to legalise collection of biometric data of mere suspects. A draft Bill — Identification of Prisoners and Arrested Persons Bill, 2020 — is likely to be tabled in the coming monsoon session of the Parliament.

The proposed legislation will provide legislative backing far beyond the mere collection of fingerprints. The biometrics will include foot and palm prints to photos, iris and retina images and voice samples.

“At a time when the rest of the world is realising the potential for abuse of such technologies, India is introducing more and more of them without first putting in place a privacy protection law,” said Dr C Ramachandraiah, a public policy expert.

The Telangana police have been using the FRS since August 2018. “We have been able to crack several important cases using this software. It doesn’t matter if we don’t know an offender’s name, we will certainly get him by his face,’’ says Rachakonda Police Commissioner Mahesh M Bhagwat.

Related news: Chennai police’s use of facial recognition technology can do more harm than good

Similarly, Punjab police have adopted an app called Punjab Artificial Intelligence System (PAIS). The app helped the police digitize its records and analyse a crime using FRS and other emerging technologies.

The Chennai Police have been using FACETAGR technology, which involves an AI-based face-recognition app that can be used in CCTV cameras as well as smartphones.

Faces within a crowd can be compared in real time with facial features of criminals and other wanted persons available in the police database. However, to track the movements of criminals 24X7, the database would include not only ‘criminals’ but almost all citizens so that the identity and address of a suspect caught on a CCTV camera or a smartphone can be instantaneously traced.

Major concerns

The main argument against the introduction of FRS is that it is open to misuse and exploitation in the absence of a privacy law.

“There is no legal basis for this untested technology which is an act of mass surveillance system. Due to high inaccuracy rates coupled with the use of law enforcement, it throws up risks of bias that have a high probability in causing coercive action,” said the Internet Freedom Foundation, an advocacy group working in the area of digital equality.

From building an underlying database of people from public protests to running it on crowds of people attending rallies, this system can have far-reaching surveillance applications, directly impairs the rights of ordinary Indians from assembly, speech and political participation.

The use of such technologies, where consent of the people is not taken, goes against the spirit of the Supreme Court’s landmark judgment in 2017, ruling privacy as a fundamental right. The FRS can use both video and static images as input to check a person’s credentials against a database. Since the software runs on an Artificial Intelligence platform, it has the ability to improve over time.

No defence

At present, Indian citizens have little or no defence against misuse of surveillance technologies because there is almost no regulation to guide the use of FRS.

“This lack of any regulation is what the police seem to be taking advantage of,” says N S Nappinai, cyber law expert and a Supreme Court lawyer.

“The right to privacy judgement of the apex court clearly says that you need laws to allow the State to do it,” he said.

Related news: Amit Shah says Delhi cops used facial recognition to pin ‘rioters’

“There is a perceptible rise in national security being a central premise for policy design. It is worrying that technology is being used as an instrument of power by the state rather than as an instrument to empower citizens,” a member of the Internet Freedom Foundation said.

When linked to a common citizen database, such as Aadhaar or voter records, the FRS becomes a classic example of mass surveillance. Such a system allows the enforcement authorities to conduct surveillance on citizens.

The Hyderabad MP and president of All India Majlis Ittehadul Muslimeen (AIMIM) Asaduddin Owaisi had opposed the introduction of FRS in the municipal polls in February this year, saying it amounted to a violation of right to privacy.

“It doesn’t have any statutory basis and serves no legitimate state aim,” he had said.

“If the aim of the State is to address the issue of impersonation during elections, it should explain why existing procedures for fraud-detection are inadequate or how this technology will augment its efforts,” Owaisi said.

The experts also argue that using facial recognition system was contingent upon the creation of large databases of “facial contours and features” of citizens, and such databases were susceptible to breach and misuse.