UGC’s new brainwashing machine: The end of history as we know it

From the recent report on the University Grants Commission’s draft history syllabus at the undergraduate level, it appears that the apex body has metamorphosed into that magaj dholai jantra that is likely to rob young citizens aspiring to enrol for higher education of critical thinking skills and ability to discern facts from fiction

;

Three years after the end of the Emergency, in 1980, Satyajit Ray made the film Hirak Rajar Deshe (In the Land of the Diamond King). The film, a dystopian fantasy science-fiction, was a scathing criticism of authoritarian rule and probably the most political of all Ray’s films.

The core story revolves around the adventures of Goopi and Bagha (originally two simpletons in rural Bengal, having aspirations to become famous musicians in spite of having little credible talent but who, thanks to their chance encounter with the king of ghosts, receive magical powers and acquire fame and wealth) in the Land of the Diamond (Hirak), famous for its riches. Once there the duo realises that all is not well. The king, a despot, has reduced the subjects to a state of destitution in his greed to centralise all power and resources. A megalomaniac, he has surrounded himself with his coterie of blind followers who only sang his paeans and accepted his decisions unquestioningly.

The king strongly believed that mass education would make the subjects wiser and less subservient (Joto beshi podhe, toto beshi jaane, toto kam mane). Therefore to muzzle all voices of dissent and criticism he along with a crazy royal scientist invents the magaj dholai jantra (brainwashing machine), which can brainwash people once they are forcibly thrown inside it.

From the recent report on the University Grants Commission’s draft history syllabus at the undergraduate level, it appears that the apex body has metamorphosed into that magaj dholai jantra that is likely to rob young citizens aspiring to enrol for higher education of critical thinking skills and ability to discern facts from fiction. At another level, a Parliamentary Standing Committee on Education is seriously considering a report titled ‘Distortion and Misrepresentation of India’s Past: History Textbooks and Why They Need to Change’ prepared by the Public Policy Research Centre (PPRC), and is likely to introduce some drastic changes in school history textbooks published by the NCERT, which are currently in use in a large number of schools across the country.

While curricula (syllabi and textbooks) require revision from time to time, the propositions raise serious concerns about the future of the education system in India and history teaching in particular. Questions also arise as to whether these recommendations emerge from genuine concerns to upgrade the education system or simply to suit the political agenda of the ruling regime and its ideological mentors.

What is at stake?

A close scrutiny of the two proposals reveals a striking similarity. The UGC, for instance, recommends the introduction of a new paper titled ‘Idea of Bharat’, which includes themes like ‘Understanding of Bharatvarsha’, ‘Eternity of Synonyms Bharat’ and ‘The Glory of Indian Literature’ (read religious literature like the Vedas), among others. The PPRC report (pp 100-101), on similar lines, proposes the need to re-write history textbooks to emphasise “the glorious part of Indian history, including our civilisational greatness and the contribution of Indian civilisation to the world vis-à-vis scientific know-how present in the ancient period, developments in the field of medicine, the value of Sanskrit language, rationality behind Vedic rituals”, etc. In the former, there is a strikingly reduced focus on the medieval period (as seen in the removal of key themes like the Delhi sultanate and Akbar). In a similar vein, the latter refers to the medieval period as the ‘Dark Age’, which it argues was characterised by “systematic desecration of Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist temples, as well as places of learning and knowledge” and hence, proposes that the “glorification of the Delhi sultanate and the Mughal period must be brought to an end”.

Also read: Mom cooks, dad reads: Kerala plans gender audit of textbooks

Needless to say, both the proposals have evoked sharp criticism from a large body of academicians, especially historians, research scholars and the general public. In particular serious concerns have been raised over the way history has been categorised along communal lines by pitting ‘the glorious Indian past of the ancient period under Hindu rulers’ against the ‘dark medieval times’ under the ‘barbaric and despotic rule of the Muslim rulers.’ It is being argued that this kind of periodisation in history is reminiscent of our colonial past when writers like James Mill categorised Indian history into Hindu, Muslim and British periods.

A Scottish economist and political philosopher, Mill, in his massive three-volume work ‘A History of British India’ (1817) argued that before the coming of the British, India was under the tyrannical control of Hindu and Muslim rulers whose reigns were characterised by religious bigotry, caste discrimination and superstitious practices. He considered European civilisations to be superior to all Asian societies and espoused that India should be brought under British rule, which would not only deliver Indian people out of the darkness but ensure progress and enlightenment to all. One wonders how a similar argument can be acceptable today.

History is a discipline of knowledge based on rigorous research that enquires about the past and constructs it based on findings corroborated by a range of evidence – archaeological, literary and oral narratives. Its objective is never to glorify the past, create heroes or romanticise events. Nor is it supposed to vilify or demonise certain personalities or communities unless evidence suggests otherwise. That is the basic difference between a myth and a historical enquiry though the former does have a role to play in a community’s cultural life. The UGC’s proposed new syllabus and the PPRC report have blurred the distinction between the two.

Classifying periods in history as ‘Hindu’ or ‘Muslim’ or otherwise is fallacious as it tends to characterise a period merely based on the religious beliefs of the ruling class and overlooks the existence of a range of belief systems and practices followed by commoners as well as the rich and powerful. Not all rulers in ancient India followed Hinduism while both during ancient and medieval times Hinduism and Islam were subjected to questioning from within and outside (Buddhism, Jainism, Bhakti and Sufi traditions to name only a few). Should all that be devalued and not be the subject of historical enquiry?

Moreover characterising any period as ‘glorious’ or ‘dark’ is problematic as it tends to provide a monolithic and homogenous view of the past. Historical research and existing scholarship show that the medieval period under the Sultanate and the Mughals in the context of the Indian sub-continent facilitated developments in the spheres of trade, administration, culture, literature and art and architecture. The cultural syncretism that characterised the reign of Akbar and his successors needs mention here as seen in the many translations commissioned during their reigns. Both the epics Ramayana and Mahabharata as well as many other Sanskrit texts were translated into Persian during Akbar’s time. While one cannot ignore the fact that many Hindu places of worship were demolished during the Mughal rule, historical evidence suggests that the rulers including Aurangzeb made generous contributions towards the construction of a number of Hindu temples. Apart from the several political alliances that Akbar forged with a number of Rajput chieftains many of whom were subsequently inducted in high administrative posts, research shows that the number of Hindu mansabdars (government officials and military generals) in the Mughal administration rose to the highest during the reign of Aurangzeb. This suggests that there was a degree of harmonious co-existence between the two communities born out of the political exigencies of the time.

While the UGC draft syllabus refers to BR Ambedkar only as someone who drafted the Indian Constitution and completely overlooks his consistent effort to eradicate the caste system, the PPRC report is evidently evasive about the existence of caste hierarchy and the contestations of the resultant discriminatory practices that have characterised the history of India right from the ancient period. The two proposals further fail to address the issue of gender adequately. Can it be claimed that in ancient India, women, in general, were educated and held in respect when evidence suggests that such privileges were restricted only to a select few, especially those belonging to the upper varnas, while others were located way down in the social hierarchy, with little or no access to education or property? Why such questions are left unaddressed in these documents is anybody’s guess.

Why this fuss over history?

What explains this fuss over history? Why is it that history, whether it is in the context of the school curriculum or higher education, always at the centre of controversies? To unravel this question the location of history in the context of a nation-state requires unpacking.

The emergence of nation-states during the 19th century necessitated the development of a national citizenry imbued with a sense of national pride and a sense of loyalty towards the motherland/fatherland, as the case may be. One of the significant ways this was to be achieved was through developing a national system of education. While civics was introduced as a school subject to inculcate among the young citizen’s obedience and patriotism, history had to be taught to instil among them a sense of oneness through the construction of a shared identity. Hence the need to glorify the past, create heroes and construct a common heritage that would act as a glue to unify a diverse populace and iron out the differences. A close examination of the history of nation-states in Europe explains this.

In the context of changing political regimes within nation-states, with support bases from divergent social groups and communities, history then becomes a contested site, where differing ideologies with opposite agendas clash. This explains why from time to time the history curriculum and textbooks are subjected to controversies and change. This also helps to understand why they become the repository of selected knowledge and why certain historical figures, events or processes capture the limelight during specific periods of time while others are pushed to the margin, totally ignored or constructed negatively.

Understanding the Indian context

In the post-colonial years, India as a newly emerging nation-state was confronted with the task of nation-building and creation of a national identity strong enough to weld together the diverse cultural loyalties and suppress the divisive regional forces and create a responsible, obedient and patriotic citizenry. This anxiety found expression in successive government reports (Mudaliar Commission 1952-53, Kothari Commission 1964-66) and the manner the national curriculum frameworks for school education were conceptualised. For instance, in spite of certain limitations the first two national curriculum frameworks (introduced during two successive Congress regimes in 1975 and 1988) upheld an idea of India that was based on secular values and celebration of its pluralistic culture. The memories of Partition and the bloody communal riots perhaps necessitated the construction of a past that upheld a history of harmonious co-existence and cultural amalgamation. At its core was the Nehruvian idea of a pluralistic nation based on ‘unity in diversity’ and the principles of equality, social justice, and secularism.

The Nehruvian idea of India as a nation was and continues to be challenged by the Hindu Right in the form of Hindutva, or what is called ‘cultural nationalism’. It envisions the construction of a Hindu Rashtra that projects India as a Hindu country, reclaims it exclusively for Hindus and thereby reduces the Muslims and Christians as ‘cultural outsiders’. This found reflection in the National Curriculum Framework for School Education (NCFSE) 2000 introduced during NDA I. It redefined the national identity by embedding it in a Hindu majoritarian, patriarchal and upper-caste ethos. It was severely criticised for undermining the Constitutional values of secularism and democracy, promoting cultural revivalism and doing away with rational discourse. So when the NCF 2005 was operationalised during the Congress-led UPA I, it aimed at purging the education system of the attempted saffronisation and reiterating a national identity based on the ideals of secularism, egalitarianism, pluralism and social justice. The history textbooks that were conceptualised were the culmination of the efforts put together by a group of established historians from diverse perspectives and include the latest trends and themes in historical research.

Unfortunately, it is these textbooks that are likely to be replaced. Before the regime change happened in 2014 and after that, there have been several indications that drastic changes are being planned to change the education system along the lines of Hindutva. Whether it was the dropping of the celebrated author AK Ramanujam’s critical essay ‘Three Hundred Ramayanas’ from the reading list of the history syllabus in Delhi University (2011) under pressure from the Hindu right, the former HRD minister Prakash Javadekar asking for the rationalisation of the school curriculum (2018) or the erstwhile culture minister Mahesh Sharma’s demand to form a high-level committee to rewrite the history of India (2018), it is quite clear that concerted efforts have been underway to polarise communities and alter the very character of the Indian society and polity.

The proposed changes in the history syllabus by the UGC and the recommendations by the Parliamentary Committee for rewriting school history textbooks need to be understood in this context.

What lies ahead

For a thriving democracy, it is important to have a culture of dissent and critical enquiry that can nurture the multiplicity of differing perspectives and rational discourse. Educational institutions like schools and especially colleges and universities are meant to provide that space where young minds can engage in debate, discussion and questioning. Should they be force-fed with concocted stories in the name of history that teaches them to passively accept an unqualified glorification of a past that was ridden with gender discrimination and caste-based atrocities?

Can a syllabus, which is poorly crafted, include readings by lesser-known scholars known more for their closeness to the ruling regime than their scholarship and seeks to promote an understanding of history that is more akin to ideological propaganda of a certain political hue be acceptable? Or should the young generation be encouraged to engage in a critical enquiry corroborated by the recent trends in historical research and historiography that throws light on the untold histories of marginalised communities, their struggle and agency and thus learn about the past that allows them to develop a better understanding of the present?

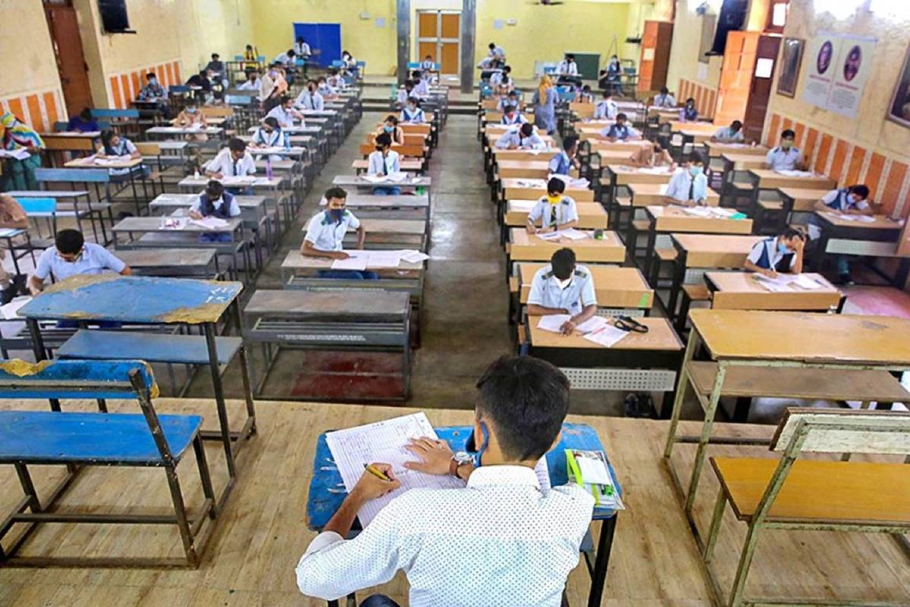

The huge demographic shift that has occurred over the last two decades has brought many from the margins across class, caste and gender into the fold of higher education who are aspiring for a better future. The diversity in the classrooms at different levels is palpable. Can they be bulldozed into a magaj dholai jantra? It won’t be long when they would see through the smokescreen of concocted ‘history’ that would contradict their lived realities. The strings are in the hands of the young generations and it is for them to decide how they want their future to be. If you are still unsure, watch Hirak Rajar Deshe and you may find the answer!

(The Federal seeks to present views and opinions from all sides of the spectrum. The information, ideas or opinions in the articles are of the author and do not reflect the views of The Federal).

(The writer works in the area of curriculum development and teacher education. She holds a PhD in Sociology of Education, and is based in Delhi).