How female deities helped foster caste violence in TN

The film revolves around an adolescent girl named Yosana, who belongs to the Puthirai Vannars caste, (which is the most oppressed Dalit sub-caste group) and what happens to her when she crosses the boundary laid down by caste Hindu villagers.The script while dealing with caste discrimination as a major theme also talks about how women are the first target, when it comes to asserting one's 'upper caste' identity.

The COVID-19 brought the concept of ‘new normal’ in people’s lives. But there is one ‘normal’ that continues to thrive for centuries, which is caste-based atrocities and caste discriminations. Reams have been written about caste injustice, and it has also been extensively documented. Demonstrations and protests have been held against these unfair and cruel practices and they continue even today.

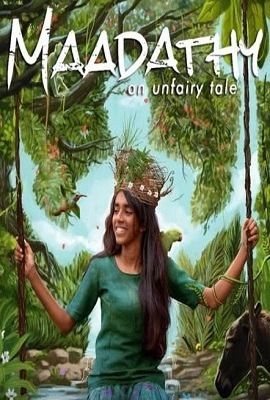

Litterateurs, filmmakers and social activists too have contributed their mite to create and spread awareness about this malaise that afflicts our society. Well-known Tamil poet Leena Manimekalai is one of them. And, her latest Tamil film, ‘Maadathy’, released on Neestream on June 24, focusses on this issue, which never seems to go away.

The film revolves around an adolescent girl named Yosana, who belongs to the Puthirai Vannars caste, (which is the most oppressed Dalit sub-caste group) and what happens to her when she crosses the boundary laid down by caste Hindu villagers.

The script while dealing with caste discrimination as a major theme also talks about how women are the first target, when it comes to asserting one’s ‘upper caste’ identity. The film also has some sub-plots like social hierarchy and discrimination within the same caste, assertion of masculinity, relationship with nature, particularly of river and beliefs in village deities.

In an interview with The Federal, Manimekalai talked about how she got interested in the Puthirai Vannars community.

In an interview with The Federal, Manimekalai talked about how she got interested in the Puthirai Vannars community.

Also read: One is identified, marked if they discuss caste in films: Director Mari Selvaraj

“While I was researching on sexual violence, I came to know that Puthirai Vannars are constantly displaced. But why, when their population is very small, I wondered? So, I learnt that they are powerless and sexual violence is normalised in that community. And, because of this some resort to female infanticide. In order to save their women, the community moves from one place to another continuously.”

“Maadathy is a female deity worshipped in southern part of Tamil Nadu. There are many versions about the story of Maadathy and this is my version,” she added.

Puthirai Vannars – the lowest of the lowest

The Puthirai Vannars, a scheduled caste community, which figure in the film are basically dhobis. The term ‘Vannars’ refers to washermen, who collected clothes from households and did their laundry for them. They are also known by other names such as Puthara Vannars, Puruda Vannars, Podhara Vannars, Thurumbar, Raappaadigal (nocturnals), etc.

Just like untouchables, the Vannars, who are in the lowest of the lowest rung in the caste ladder, were once considered as ‘unseeables’.

BR Ambedkar had once written about them: “In the Tiannevalley District of the Madras Presidency, there is a class of unseeables called Purada Vannans, who are not allowed to come out during the daytime because their sight is enough to cause pollution. They (leave) their dens after dark and (scuttle) home at the false dawn like the badger… No civilisation can be guilty of greater cruelty”.

Truly, their condition was pathetic back then. In Tamil literature, the novel ‘Koveru Kazhuthaigal’ (1994) by Imayam, probably was the first one to document the lives and struggles of Puthirai Vannars. It is believed that after the publication of the novel, the DMK government formed a welfare board for this community in 2009.

“Besides laundry work, they were also involved in performing the death rites of people,” said K Ragupathi, assistant professor, Department of History, Thiru A Govindhasamy Government Arts College in Tindivanam.

Also read: Will Pallars, long victims of oppression, now embrace the BJP in TN?

Many Vannars today are no longer doing jobs their forefathers did. “Due to modernisation, most of the Vannars have left their family vocation and taken up other jobs,” said Ragupathi, who has done a lot of research on this community and even written a book on them titled ‘Theendaamaikkul Theendaamai’, along with Prof C Lakshmanan.

But Ragupathi pointed out that though they may have left their traditional work they still continue to face oppression. “In a few southern districts, some of the intermediary castes ask them to perform death rituals even today,” he added. Manimekalai pointed out that not even 30 per cent of Puthirai Vannars have been educated and they have demanded one per cent sub-quota reservation.

The birth of female deities

Most of the female deities found in Tamil Nadu are born from ‘hate killings’, a result of star-crossed love affairs between inter-castes, particularly of Dalits and intermediary castes.

In these hate killings, interestingly, while the Dalit men are forgotten, the caste Hindu women, who were the victims of hate killing turn into deities. It is a fact that most of the female deities were born out of caste atrocities. Deities like Muththaalamman are the perfect examples.

Sa Tamilselvan brilliantly summed it up in his book, ‘Saamigalin Pirappum Irappum’ –“The lower caste people made these deities and temples as a sign of their opposition against the kings and caste Hindus. Over the period, due to feelings of guilt, the same caste Hindus started worshipping these deities”.

Sa Tamilselvan is a former chief of the Tamil Nadu Progressive Writers Association, the cultural arm of the CPM.

Also read: Sundar Krishnan pays ode to rich Tamil history with his collection

Sometimes, these deities are just “one day goddesses”. In some cases, once a deity has been worshipped in a grand manner during a particular time of the year, it will be wiped off the face of the earth. The idol will either be broken or they would immerse it in the water. Over a period, this became a caste ritual in itself.

“So, many of these deities have become one day Goddesses”, observed Tamilselvan.

“The deities reside in two places. One in the temples and two, in the minds of the people. If the temple of a deity is given up (possibly because of lack of maintenance) or the people forget about the deity, then we can consider the deities are dead,” wrote Tamilselvan.

According to him, the best example of a ‘dead deity’ is Kotravai. The female deity was once worshipped by the people in every village and she had a separate temple but she is not worshipped any more, he said.

Interestingly, the deity named ‘Moodevi’, which is neglected by all other castes today is worshipped by Vannars. The deity has one temple each in Tirunelveli and Madurai.

“Not only caste but also male chauvinism has played a role in the birth of these deities. We cannot separate caste and male chauvinism,” said Tamilselvan, adding that the concept of creating female deities and worshiping them somehow helped to foster the continuation of caste atrocities.