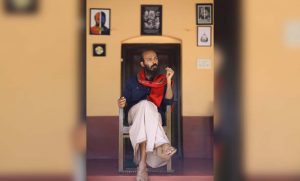

Mangaluru Days: Why Kannada director Raj B Shetty is the talk of the country

Shetty recounts the joy of making a film in Mangaluru, and how the gamble of a theatre release for Garuda Gamana Vrishabha Vahana paid off

Every corner of the byzantine lanes of Mangaluru, a profusion of stories lay undiscovered — and waiting to be told. Knowing the story is one thing; capturing it, another. Mangaluru-based writer-director Raj B Shetty is trying to bridge this gap by telling the city’s tales: in 2017, he made Ondu Motteya Kathe, a quirky story of a bald Kannada teacher, and, in 2021, he unleashed Garuda Gamana Vrishabha Vahana (GGVV), a gangster tale set in and around Mangaladevi, from which the city draws its name.

With a veritable babble of local languages (in the spoken pecking order, Kannada comes after Tulu and Konkani) and a kaleidoscopic blend of cultures, not to forget its coastal cuisine, there is no city in India quite like Kudla, as Mangaluru is called locally. [In fact, there are at least five names for the city in five different languages].

“Stories are everywhere, but you need to tell them. Nothing travels or moves (you) like local stories,” says Shetty, who wrote directed both the films with an all-Mangalorean crew in real locations.

Released in theatres to thunderous response last November, despite COVID’s long shadows, GGVV also emerged as one of the most critically acclaimed films of 2021, and the recent OTT release (on Zee5) made the film, as Shetty puts it, “travel farther and deeper”.

Encomiums are still pouring in from the likes of Anurag Kashyap, Gautham Vasudev Menon, Ram Gopal Varma and Charu Niveditha (Tamil writer and critic).

In a long conversation with The Federal, Shetty, who also played major roles in both the films, walks us through the alleys of Mangaluru, where he shares tidbits about the film, and why he is at peace with himself in his favourite city where he can meander from nowhere to somewhere to everywhere. Anywhere he travels for work or fun, he rushes back to Mangaluru, like a bird returning to its coop.

On we go.

You were extremely lucky to have had a theatrical release and run (when COVID cases dropped before the spike). Was it a calculated risk or just that you did not want your work to end up as another OTT film?

Since GGVV was conceived for a big-screen experience, we were very keen to have it released in theatres. Be it the camera, sound or any technical aspect, we had the film shot keeping the theatre experience in mind. I knew exactly how people would experience particular scenes on the big screen. So, theatrical release was inevitable — the only question was when. The date (November 19, 2021) was a calculated risk, but then I was very convinced with the release though many were against the idea. Luckily, I don’t have the habit of meeting astrologers, and thus it happened. (Laughs)

Looking back, I must say it really paid off. Release, even a month later, would have been tough or impossible. Sometimes, you must go ahead with what your mind says no matter what the world tells you to do — or not to. There is nothing more satisfying than the theatre experience, for film-makers and viewers alike.

Also read: Exclusive: Malayalam film ‘Nayattu explores behaviour, not identity’

Your biggest film, first day, amid COVID shadows. What was going through your mind?

Frankly, I was not that nervous, maybe because we were confident about the product. I knew the film would be no easy experience though it has a certain rhythm to it. As intense as it is, I did not want the film to be projected — it may be finally — as a mass film either. That is why the only poster we released had an abstract tinge to it. Even the complex title is a reflection of that thought. [The working title was HariHara] Three days before the release, we had a premiere show, where we roped in the right kind of audience just to gauge the mood. It took off by the third day to have four weeks of uninterrupted run in Karnataka. In Mangaluru, where the film was born and raised, I think it’s the biggest hit for a Kannada film. Elsewhere also, it ran well, especially in Hyderabad, which was a real surprise. In Tamil Nadu, it was picking up really well, but then Maanaadu hit the screens.

So OTT (direct release) was never an option at all…

Yeah, I kept telling my team that GGVV is our visiting card, which effectively means we have not reached a position where we can do business yet — the card is to make business. The film travelled, and penetrated, to other parts of the country, by sheer word of mouth. OTT was to happen later. In any case, the big-screen experience for the audience and the crew was something I can’t even describe. As they say, it has to be seen to be believed. Now, with the OTT release (on Zee 5), it’s on another plane altogether.

Answering your query, we could have done many things, but as far as I am concerned, GGVV is a film which I conceived four years ago, and once the film is out, it’s over. It is up to the audience now. Some may call it a masterpiece, some lukewarm, and some damp squib. It’s all part of the game, and we have moved on. At the risk of sounding philosophical, let me say I am no longer the same person who made GGVV.

Also read: Minnal Murali takes off in style, ready to fly to the next level

GGVV was starkly different from your first film, Ondu Motteya Kathe, a sombre tale made on a shoe-string budget. Few expected you to come up with a gangster tale.

I did toy with some lighter subjects, but the idea was to get into unknown terrain and experiment. So we, as a team, did intense research, picked up new things and landed (on) what we have finally made. Maybe that’s one reason why the film looks fresh or different.

It’s strange when you use the word ‘unknown terrain’ after having shot in Mangaluru, your own backyard. Have you shot the film in real locations?

The idea/magnitude was certainly new territory. Our locales were in and around Mangaladevi, mostly because a Mangalorean would easily know had we shot it elsewhere. They know every nook, corner, tree or even a banner on the streets at Mangaladevi, in particular. Whatever you have seen in the film was shot there. I wanted the film to be as truthful as possible and, as I said earlier, “this too was part of the whole experience”.

Shooting a film about Mangaluru in Mangaluru — what did the locals say and how did the shoot go?

The shoot was smooth, rather uneventful because we knew how to deal with the locals and how to respect their culture, privacy and way of life. Probably elsewhere in Karnataka, people gleefully stop by to have an extended look at the stars or the shoot, but in Mangaluru, they really don’t care and get going with their own business/work. Cinema can wait, they can’t. At no stage did we obstruct or disrupt anyone’s movement or work; instead, we shot in the midst of it all.

It’s revealing when you say Mangaloreans are not obsessed with films altogether. How do you view the film culture of the city?

Big footfalls are assured (only) if it’s a star-driven or exceptional film. For instance, even Tulu films, with a restricted market, have done well whenever the content is exceptional. Other language films also do well only if they have something big to offer. For ordinary films, you may not even get distributors.

I would say they are ‘reluctant film-watchers’, and you need a strong reason/push to make a Mangalorean watch a film. Few would take pride in being a film-maker, but they take real pride when they identify themselves with Yakshagana or Huli Vesha or even Kambala — and no, religion does not play any role here. In a way, it’s heartening to keep oneself connected more with local culture and associations — perhaps it’s about the cultural moorings the populace is so ingrained with.

Also read: Puneeth’s death a huge loss for new-wave Kannada cinema

Are you also a reluctant film-goer?

Oh, yes. It needs some real prodding for me (also) to watch a film. There was a period when I tried to watch as many films as possible, but I could not prolong it at all. That is a way of life I am comfortable with.

Yet, if you can share some of the films really moved you recently.

(Long silence)

Pedro (Kannada) and Pebbles (Tamil), for sure. Then, I Dream in Another Language and Embrace of the Serpent.

Has the industry not wooed you to Bengaluru, where all the action is?

It has, but I don’t think I can move away from this place, where I am totally at peace with myself. Even a simple thing like playing volleyball in the evenings with my friends… it makes such a big difference in my life when there are any cultural activities, which I regularly take part in. I would call this ‘quality of life’. (Only) if I live (well), I can write (well). I live here, I breathe, I can roam around. If I shift to Bengaluru I know what kind of life awaits me and I shudder at the thought.

Tulu (the most spoken language in Mangaluru) films also make occasional headlines but they fade away fast. Ever thought of making a film in the language. Perhaps for a bit of hand-holding?

Yes, I might make or at least produce a Tulu film, but a high-budget (commercial) flick may not be financially feasible. If a brilliant script comes my way, we will certainly make a Tulu film. Even in GGVV, it’s the Tulu culture that comes alive. So, that way, I think I can bridge the gap. Culturally, Tulu and ‘Mangaluru Kannada’ are so entwined that people in other districts of the State would find it tough to even understand the language used in the film. Only one character in GGVV speaks a ‘different’ Kannada.

The traction for regional cinema is growing, especially after the OTT explosion. The South is having a great run, but Kannada has not caught up yet.

The quality of our films is one reason why we are struggling to catch up in the race. For instance, Malayalam cinema has writers and stars, Tamil has stars and directors and we have (predominantly) stars. Hence, most of our films are star-driven and do very well in local theatres. For a star to travel outside of the State, you need strong content.

Earlier, we had some of the best film-makers in the country, such as Shankar Nag and Puttanna Kanagal. Such was the rage that Kamal Haasan would travel to Bengaluru just to watch Kanagal films. It’s a cycle; from its peak, it has plummeted and I am sure we will rise again. I think a churn is happening and it’s time to make use of the opportunity.

So when is the next film — let’s call it the Mangaluru Trilogy — coming up?

(Laughs aloud) I like the term ‘Mangaluru Trilogy’ though it’s too early to discuss it. One thing is sure — this place has a profusion of stories that need to be told. Many told me that had I placed GGVV elsewhere, say Bengaluru, it would have been a bigger hit, which I don’t agree with at all. The GGVV experience has to have three things: character, culture and locality. It could not have been shot anywhere else.

One reason why Mangaloreans may not connect with cinema, in general, could be because not many have explored the region on celluloid. So, there are 1,000 stories waiting to be told. Take any cinema, nothing travels or moves (you) like local stories.

Mangaluru is known for its coastal cuisine. For a tourist, any favourite eateries you can suggest?

Hotel Narayana (Bunder), Giri Manjas (Car Street) and Machali (Kodialbial). For fish, that is.