Production Linked Incentives — like curate’s egg, good in parts

In its overweening, obsessive desire to promote Make in India at all costs, the PLI scheme has ignored some basic economic concerns and principles

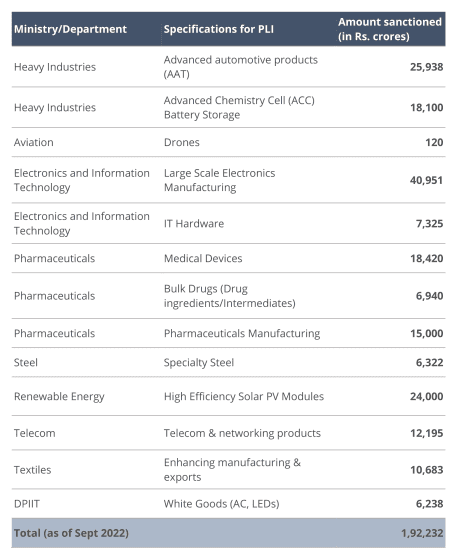

Launched in March 2020 targeting the electronic sector, the Centre’s Production Linked Incentives (PLI) scheme is the Narendra Modi government’s attempt to give impetus to big-ticket manufacturing. The goal is for the sector contributing 25% of the GDP by 2025 from the extant 16%. Naturally, it would provide employment opportunities as well.

That there are as many schemes as are key drivers identified by the government in conjunction with Niti Aayog testifies to its anti-one-size-fits-all character. The government realized that each industry has its unique problems and opportunities and hence eschewed the general approach.

The other virtue of PLI is it is awarded and disbursed only when results are shown in terms of incremental production which is why it is also called piece-rated incentive. It also is WTO-compliant as it steers clear of trade distorting export subsidies and instead is secular — incentives are available no matter you export or cater to the domestic market.

Also read: Engineering sector MSMEs seek production-linked incentive scheme

The reason for stocktaking at this juncture of the scheme done herein is to see why it hasn’t nudged production significantly except in the cell phone sector where all the big boys like Samsung and Apple are fired up and not only embracing the scheme with alacrity but are also beginning to export.

Make in India

But as Raghuram Rajan points out, in its overweening, obsessive desire to promote make in India at all costs, it has ignored some of the basic economic concerns and principles. For example, PLI has passed the MSME sector — accounting for 36% of domestic production and 40% of exports — by completely in its effort to woo the big boys of each sector. This flies in the face of its avowed Swadeshi plank that swears by small domestic producers.

It has also gone out of the way to promote domestic manufacturing by increasing import duties lest domestic manufacturing isn’t considered unworthy and imports are preferred. Rajan cites the example of cell phone industry.

Import duty on cell phones were increased to 20% in April 2018 as a precursor to PLI-baited make in India. The upshot — iPhone 13 pro max available in Chicago for Rs 92,500 while the same model in India is priced at Rs 1.29 lac, a markup of nearly 40% thanks to the swadeshi principle of protection to domestic industry which denies the Indian buyers the advantages of dumping consisting in lesser prices for imported products. In other words, Apple like Sony of the 1970s would have been happy to sell iPhone cheap in India vis-a-vis the US but for PLI.

Other issues with PLI

Not only this, value addition is completely ignored by PLI so much so that a cell manufacturer is cossetted with PLI subsidy even if he imports all parts and only assembles them in India. This effectively takes up the the 6% PLI subsidy into a hefty 25% to 30% subsidy of value addition considering the fact that the incentive is on the invoice price whereas the value addition is a tiny fraction of it.

It also pays no importance to cost cutting so long as production is increased. Indeed, the manufacturer has no incentive to worry about costing and pricing as the incentive is quantity based.

PLI is also criticized for its selectivity bordering on the whimsical — textile industry making the grade in the list of 13 sector notified thus far but strangely the leather industry being left in the cold out of reckoning. The pat answer is the government has a limited budget allocation for each scheme so much so that when the actual eligible incentive exceeds the allocation, there is rationing of the incentive among the claimants.

Also read: Union Cabinet approves production-linked incentives worth ₹2-lakh cr for 10 sectors

The biggies of the automobile sector are unable to meet their incremental turnover commitment in view of shortage of chips so crucial in modern cars. But the PLI scheme is a martinet, brooking no exception even on genuine commercial grounds. Supply chain dislocation with the ongoing Ukraine war similarly begets no sympathy for shortfall in production.

Globally, manufacturing is incentivized variously — like creating special economic zones; tailored logistics and specific incentives; tax- and credit-based schemes and research and development-based approaches. India’s quantity-based PLI scheme is akin to the ‘piece rate’ method. Apart from being simple, it is considered the best method to ensure higher productivity. Special incentives for R&D while appearing to be progressive, gives a leg up to charlatans as the Indian income tax dalliance with it shows.

PLI has shown results in the cell phone segment of the electronic sector. Apple’s vendors led by Foxconn have made a commitment of a minimum incremental production of Rs 25,000 crore of mobile devices in FY23 beginning from April 1.

It is a threefold jump in the commitment of minimum incremental production over FY22. But as said earlier, this comes at a heavy price for the domestic customers with stiff import duty effectively discouraging imports. In short, PLI is the old protection to domestic industry model warts and all with little concern for the domestic consumer who otherwise could have gorged on cheap imports.