Caste subjugation: How we deny dignity to hereditary Bharatanatyam dancers

Those who consider themselves to be feminists should reflect on the language they use to describe victims of any kind of violence

Often on Women’s Day, high-achieving women from different spheres of life are celebrated. Well, I am attempting something quite the contrary. I want to bring the much-needed nuance about structures of power and the inequities that exist amongst women and the need to reflect on these issues before attempting sweeping “progressive” pieces of speech and writing.

As I reflect on these inequities amongst women, I would like to focus on the arts, as my involvement and passion lies there. The arts are, after all, spaces where caste and class privilege work in tandem in the building of cultural capital. The subjugation of women in these spaces is insidious, particularly in the Indian context where much of what is considered as art in post-Independent India is a result of the processes of cultural nationalism that were driven by caste-privileged members, both men and women, who were adherents to patriarchal Brahmin orthodoxy.

The problematic history of Bharatanatyam

As I write this piece, there is an ongoing social media debate on Instagram about the Bharatanatyam training of American rapper Doja Cat. Twenty-seven-year-old Doja is of African descent from her father’s side. The Instagram page called Brown History talks of Doja as a child raised in an ashram in California for about four years, where she learnt bhajans and Bharatanatyam. The page also expands on a false, but popular history of Bharatanatyam which claims that the British “banned” the dance and that the artform later found a resurgence in Free India.

The post and the comments below elucidate the phenomenon that I wish to write about here. This Instagram post has inspired a series of articles on entertainment news portals talking about Doja’s connection with Bharatanatyam upholding orientalist Brahminic narratives around the reform and reinvention of the artform and celebrating the greatness of Indian culture. It’s a kind of neo-cultural nationalism that we are all too familiar with – the genre of writing that masquerades as news when it is a not-so-subtle nudge to jingoism.

Also read: ‘Casteing’ a discriminatory gaze on classical and traditional folk arts

It must be stated that under this Instagram post on Doja Cat, there are people questioning this problematic history of Bharatanatyam. There is also an insistence of speaking about the appropriation of the artform by Brahmin elites. And then there are both Hindu fundamentalists and self-styled “progressives” defining who and what a “devadasi” is. Some call them priestesses who were devout singers and dancers, while others claim they were prostitutes, or sex slaves of Brahmin temple priests, or as women who were subject to sexual abuse accompanied with voyeuristic narratives of sexual oppression.

The erasure of the hereditary performers

These narratives are also iterated in popular films, literature, and even scholarly works, with no empirical or critical analysis. There are also problematic comments that conflate the existence of Dalit communities such as Jogatis and Matammas with the Shudra castes that originally practised Bharatanatyam.

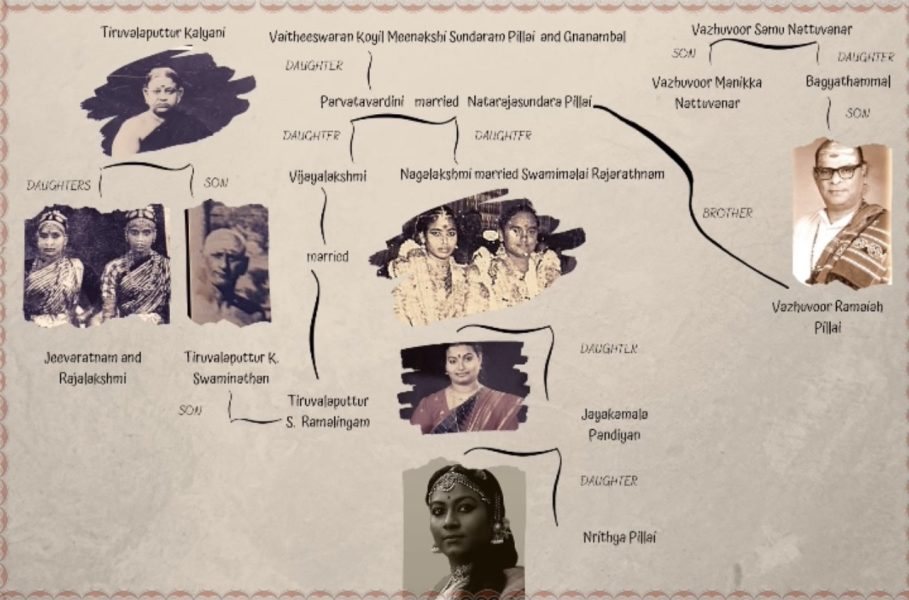

I belong to this latter caste location. In my case, when we do a little historical digging, we find that I stand at the centre of several deeply interconnected hereditary dancer-teacher lineages, members of which have played an important role in the long story of Bharatanatyam, past and present.

In the world of today’s Bharatanatyam, the hereditary South Indian dancer is often named “devadasi.” The popular understanding of the idea of “the devadasi” is as follows: “Devadasis” existed all across India since time immemorial. In South India, they were linked to Hindu temples and often called “temple dancers”. In North India, because of Islamic influence, they were called tawaifs, or courtesans. Here’s what is problematic about this narrative as we reflect on the erasure of the hereditary performers of Bharatanatyam, a South Indian dance celebrated as India’s most practiced “classical” dance form.

“Devadasi,” as many scholars have shown, is a word that comes out of Sanskrit materials that were the focus of European Orientalist scholarship about India. It is actually not a term used frequently in the historical record (texts, inscriptions, literature, etc.). The label “devadasi” was given a new visibility during the reform debates that began in the late 19th century about 150 years ago, in which a whole range of South Indian women’s communities — from the Bahujan Melakkarar in Tamil Nadu and Kalavantulu in Andhra Pradesh, to Dalit Jogati and Matamma communities in Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh — were all lumped together for the purpose of passing legislation that would supposedly curb sex work and ultimately better the lives of these women.

The politics of dignity

Today, the term “devadasi” has morphed into a slur, a word used to refer to a woman lacking in morality. In the past, women belonging to the hereditary courtesan Shudra castes were bound to a practice of concubinage in which women had long-standing non-conjugal relationships with male elites. Of course, it had oppressive aspects to it. But calling women who functioned and made livelihoods for themselves under such oppressive constraints as “sex slaves” surely does not restore a politics of dignity to those of us from this background. Indeed, representations of our pasts in these ways are used to silence my work and my interventions in the world of Bharatanatyam today.

Nevertheless, reform movements sought to end courtesan practices by framing them as sexually immoral and degraded traditions, culminating with the passage of laws in 1947, in Free India, that criminalized them — laws which persist to this day. The solution given to the “problem” of women from these courtesan castes was marriage, in its patriarchal and oppressive form. Marriage was deemed the “respectable” way out for women artists. Importantly, reform at that point did not problematize the transactional nature of institutionalized caste-endogamous marriages that were normative during that period across all castes, including Brahmins. Not only did reform exacerbate extant problems around stigma and suspicion of women artists, it also marked the category “devadasi” with a new kind of negative connotation.

Also read: Margazhi festival: 5 controversies in history of Carnatic music, Bharatanatyam

I have been pointing out the instability of the term “devadasi” for a few years now, and yet, there is a Brahmin lobby within the Bharatanatyam world that insists that we uphold this term in public discourse. At the same time, it is significant that many practitioners and scholars of Bharatanatyam don’t question the inherent casteist violence and gatekeeping perpetuated by this “critical dance history” narrative, driven by Brahmin hegemony.

The question that should drive our discussion is this: “Which young woman from hereditary dancing castes today would want to intentionally re-inscribe stigma-laden terms like “devadasi” onto herself, and for whose benefit?” And, subsequently, one also needs to think about the kinds of rebuttals from the middle-class, anti-caste progressive circles that often centre on the “sex slave” representation.

This is why anyone who identifies as a progressive must reflect on the language they use to describe women from caste backgrounds whom they consider as victims of sexual oppression/violence. It helps no one when language like “sex slaves/prostitute” is used repeatedly. This has long-lasting effects. After all, language is a modality of power. When people from these caste backgrounds find the means to get educated and seek dignity for themselves, they are deterred and continue to be traumatised by this kind of language and the casteist and misogynist mindset that undergirds it.

And so, on this year’s Women’s Day, I hope those who consider themselves to be feminists, reflect on the kind of language they use to describe victims of any kind of violence.

(The writer, a bharatanatyam dancer, runs her own dance school in Chennai and is from the hereditary dance family of Swamimalai Rajarathinam Pillai.)