Why does India need green bonds?

The Union Budget-2022 announced green bonds to fund climate-friendly infrastructure projects that will help India meet its 2030 carbon emission commitments and the long-term promise of net zero emissions marked for 2070.

But, what are green bonds and why does India need them?

These are sovereign bonds used to raise money to finance public-sector proposals essential to help reduce carbon emissions.

It is similar to any debt instrument in a sense that it is bought by investors who put in the principal amount sought by the issuer and, in return, gets interest on maturity. The issuer is bound to use the amount thus raised to fund projects that have a positive bearing on the natural surroundings. India first issued green bonds in 2015.

In her Budget speech delivered on February 1, 2022, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman said that as a part of the government’s overall market borrowings in 2022-23, ‘Sovereign Green Bonds’ will be issued for mobilising resources for green infrastructure and policy measures like battery swapping policy for electric vehicles and performance linked incentive (PLI) scheme for domestic solar cells and module manufacturing units. The Finance Ministry has unveiled a record borrowing target of Rs 14.95 trillion in financial year 2022-23. A large chunk of this public money is likely to go into developing domestic renewable energy (RE) infrastructure because about 80% of our solar installations are dependent on import of PV cells and panels, which come mostly from China.

Also read: What Centre’s push to power plant biomass co-firing means to farmers, air quality

The Centre’s elaborate borrowing plan by way of green bonds has its roots in commitments made by India at the Paris Climate Summit in 2015, followed by further ambitious targets set by the Narendra Modi government at the COP-26 summit in Glasgow last November.

India and other developing economies have time and again emphasised that climate change and its manifestations would hit them the hardest. Several island nations are on the verge of getting submerged due to rising sea levels while frequent droughts, floods and natural disasters like cyclones have ravaged the coastal belts of countries like India. In 2009, the wealthy nations had promised $100 billion in annual climate finance to developing countries to help deal with the effects of global warming and prepare for the challenges that lie ahead. However, this promise remains largely unfulfilled with the developed world either skirting a discussion on the subject or garbing high-interest loans to nations as climate fund dollouts.

At Glasgow, Prime Minister Modi put up a humongous demand for $1 trillion in climate finance, an argument supported by Brazil, South Africa and others. However, there has been no concrete assurance from the developed countries in meeting this renewed demand so far. Meanwhile, the Modi government went ahead to announce India will reach net-zero emissions (emit as much carbon as the earth can absorb, thus reducing the Earth’s net climate balance) by the year 2070.

To reach net-zero in the next 50 years is an ambitious target, but to set the course for the impossible, India set short-term targets for 2030:

- 50% power generation from renewable sources like solar and wind

2. Achieve 500 GW renewable energy capacity installation

3. Reduce carbon intensity by 45%

4. Reduce projected total carbon emissions by 1 billion tonnes

As per the Centre’s own estimate, India would likely need $2.5 trillion to achieve its 2030 targets. A Reserve Bank of India report states that until February, 2020, India had an outstanding debt of $16.3 billion in green bonds.

Also read: Linking Ken-Betwa rivers will cost 46 lakh trees! Anybody listening?

About 70 to 75% of India’s energy needs are still met by fossil fuels like coal, which is the most polluting source of energy till date. To wane away from coal, India is investing heavily in renewables like solar. As per one Centre for Science and Environment report, India’s Renewable Energy (RE) sector received an investment of Rs 2.3 lakh crore during 2017-19. The funding requirement for 2020-22 is double, but the investments are not attuned to the targets.

At a time when developed countries have been stingy in meeting their climate finance commitments, India needs to find its own ways to boost infrastructure that will help reduce carbon intensity and emissions. Therefore, the emphasis on raising money through green bonds.

Global experience

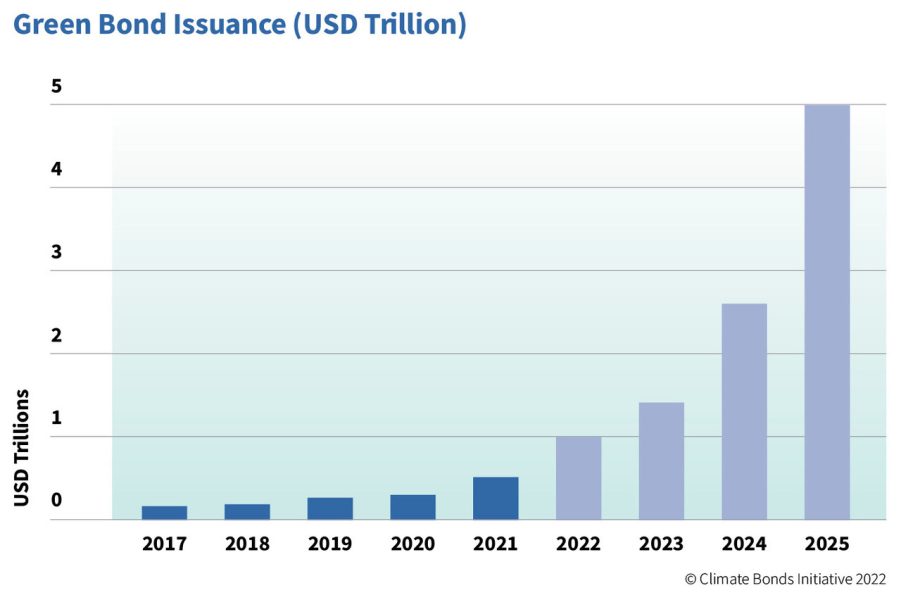

The World Bank, in association with a Swedish bank issued the world’s first green bond in 2008. According to Climate Bonds Initiative, the green bond market grew from $11 billion in 2013, $36 billion in 2014 to phenomenal sum of $521 billion USD in 2019. The value of green bonds crossed $1 trillion in 2020, as more governments and companies turn them into instruments. The collective issuance of green bonds since 2008 has been more than $1 trillion. Despite the surge, the total green bond market is just over one percent of the global bond market.

Till 2020, a total of 24 countries had issued sovereign green bonds, cumulatively worth $111 billion dollars, states Climate Bonds Initiative, a London-based not-for-profit organisation.

The years 2020 and 2021 have seen some stagnation as governments across the world focused their energies in fighting COVID-19 pandemic, but the immediate challenge posed by climate change may see the green bond market surge once again with governments getting desperate to steady their wrecking ships.