- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

Women and the Nobel Prize: A curious case of omissions

It was 1903. The Nobel Prize, something of a Johnny-come-lately in the world of honours, created by a huge endowment by Alfred Nobel, had begun to make something of a mark on the public imagination. There was a sense that those chosen for the honour were people of substance. The Physics prize that year was awarded to three people: Henri Becquerel, Marie Curie and her husband, Pierre Curie,...

It was 1903. The Nobel Prize, something of a Johnny-come-lately in the world of honours, created by a huge endowment by Alfred Nobel, had begun to make something of a mark on the public imagination. There was a sense that those chosen for the honour were people of substance.

The Physics prize that year was awarded to three people: Henri Becquerel, Marie Curie and her husband, Pierre Curie, for their work in something called ‘radioactivity’, a term Marie had coined.

That was the beginning.

The first woman had just been awarded a Nobel Prize.

In 1911, Marie did it again. She won a second Nobel Prize, this time in Chemistry, for her discovery of the elements, polonium and radium.

Curie was the first woman winner of a Nobel Prize and the first woman winner of the Physics Prize and the Chemistry Prize. This is a feat that should drive all people, even the most sober ones, to wax lyrical about the scale of Curie’s achievement. Given the rampant sexism that prevailed then, how she managed to achieve this is scarcely imaginable. As a naturalised French citizen (she was born Polish), Curie did not have the right to vote (something given to French women only in 1944) even as she was doing her adopted country proud.

Between Curie’s first and second Nobel Prizes, two other women were awarded the prize. Bertha Sophie Felicitas Freifrau von Suttner, an Austrian-Bohemian pacifist and writer won the Peace Prize in 1905 for her strident opposition to war and her work in the peace movement. In 1909, the Swedish writer Selma Lagerlof won the Literature Prize. Others followed in the years to come. One of them was Marie Curie’s daughter, Irene Joliot-Curie, who won the 1935 Chemistry Prize, with her husband, Frederic, making them the second married couple to have won the prize (Marie and Pierre were the first!).

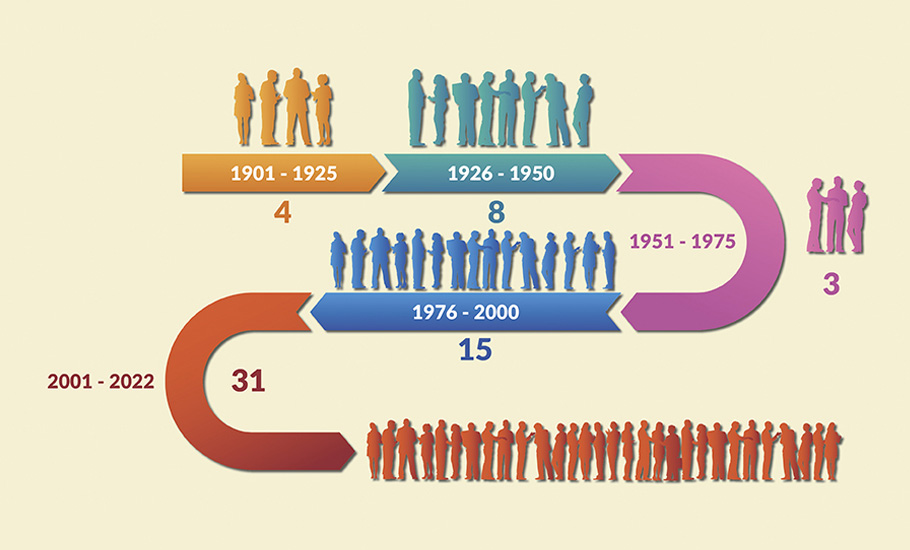

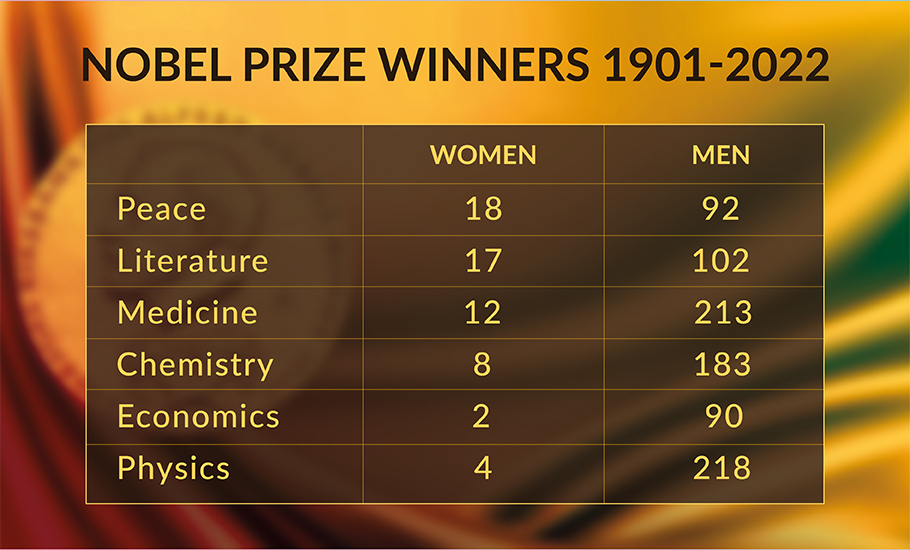

As of 2022, 60 winners have won 61 prizes in all—18 for Peace, 17 for Literature, 12 for Physiology or Medicine, 8 for Chemistry, 4 for Physics and 2 for Economics. Compare this figure with the overall numbers (a total of 609 prizes have been awarded to 975 individuals and 25 organisations) and the gender gap (or bias, if you will), is clearly evident.

Women constitute a miniscule percentage of Nobel laureates. And if one were to wade deeper into data analytics of this sort, the numbers are even more depressing.

Only nine Asian women have been awarded the Nobel Prize, for instance, seven of them for Peace. Mother Teresa (India) was the first, awarded the Prize in 1979. Aung San Suu Kyi (Myanmar/Burma) was the next, in 1991. Shirin Ebadi (Iran, 2003), Tawakkol Karman (Yemen, 2011) Malala Yousafzai (Pakistan, 2014), Nadia Murad (Iraq, 2018) and Maria Ressa (Philippines, 2021) are the other Asian Peace laureates. The two winners of a prize in a discipline other than Peace have been Ada Yonath from Israel for Chemistry (2009) and Tu Youyou from China in 2015 for Physiology/Medicine.

The share of African women is even more miniscule. In 1991, Nadine Gordimer from South Africa was awarded the Literature Prize. In 2004, Wangari Maathai became the first African woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize for her contribution to sustainable development. In 2011, two Liberian women, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf and Leymah Gbowee were awarded the Peace Prize.

Crunching data

Inevitably, most women winners of the Nobel Prize have been from the world’s more developed nations (the West, in popular parlance). That more or less reflects the pattern of all winners of the Nobel Prize.

'Nobel' prize in economics, a 20-year emoji history.

2022:👨🏻🦳👨🏻🦳👨🏻🦳

2021:👨🏻🦳👨🏻🦳👨🏻🦳

2020:👨🏻🦳👨🏻🦳

2019:🧔🏾👩🏻👨🏻🦳

2018: 👨🏻🦳👨🏻🦳

2017: 👨🏻🦳

2016: 👨🏻🦳👨🏻🦳

2015: 👨🏻🦳

2014: 👨🏻

2013:👨🏻🦳👨🏻🦳👨🏻🦳

2012: 👨🏻🦳👨🏻🦳

2011: 👨🏻🦳👨🏻🦳

2010: 👨🏻🦳👨🏻🦳👨🏻🦳

2009: 👩🏻🦳👨🏻🦳

2008: 👨🏻🦳

2007: 👨🏻🦳👨🏻🦳👨🏻🦳

2006:👨🏻🦳

2005: 👨🏻🦳👨🏻🦳

2004: 👨🏻🦳👨🏻🦳

2003: 👨🏻🦳👨🏻🦳

2002: 👨🏻🦳👨🏻🦳— IGC Cities that Work (@IGC_CtW) October 10, 2022

Take the case of the Peace Prize. Between 1900 and 1950, 40 men (39 of them white, all from the West—the only non-white was Ralph Bunche, an African American), 3 women (all white and from the West) and 5 institutions (the Red Cross won it twice) received the prize. Asia and Africa were entirely absent from the list.

Between 1951 and 2000, the pronounced Western bias began to change. Several people of non-Western origin won the prize, though they were mostly men (7 women won the prize). Among the prominent women winners during this time were Mother Teresa, Aung San Suu Kyi, Alva Myrdal (Sweden, 1982) and Rigoberta Menchu (Guatemala, 1992). Since 2001, seven more women, all of them Asian and African, have won the prize, an indication that the tide is turning.

The statistics of the Literature Prize is not very different. Between 1900 and 1950, 40 men and 5 women won the prize. Rabindranath Tagore was the sole Asian in the list. Gabriela Mistral (Chile, 1946) was the only presumably non-Western woman (and this is arguable given that most of South America speaks Spanish, a European language, and the continent is mostly culturally allied to the West).

Between 1951 and 2000, the Western bias began to ebb, but not so the bias in favour of men. There were only four women winners during this time: Nelly Sachs (Germany/Sweden, 1976) Nadine Gordimer, Toni Morrison (USA, 1993, also the first African American woman winner) and Wisława Szymborska (Poland, 1996).

Since 2001, eight women (and 14 men) have won the prize (Annie Ernaux in 2022 being the most recent), an indication that the tide has definitely turned and more than at any time in its history, the gender composition of the Nobel Literature Prize looks reasonably good.

The glaring omission, though, is that that no Asian woman has ever won the Literature Prize. The eight women winners since 2001 have all been from the West.

The inevitable questions about the scientific prizes

That most of the scientific prizes are won by Western individuals is obvious. The absence of Asians and Africans in the scientific prizes is almost always explained on the basis of the poor funding that scientific research in these continents receives.

But what is interesting is the absolute dominance that white males currently exert on the prizes. Given that the scientific establishment in the West is well-funded and women are relatively more liberated, the number of Western women winning the prize is still extremely low. What combination of circumstances would explain that? What is in the nature of how science is ‘done’ that privileges the male, even in the West?

One explanation runs thus.

Historically, much fewer positions in academia have been occupied by women. However, the ratio of women in science has increased in the last few decades. Despite this fundamental shift, the ratio of women Nobel laureates is still low, partially on account of the age discrimination of Nobel Prizes as winners are usually well-established senior researchers, usually men. The numbers of women winning the scientific prizes are therefore expected to increase in the years to come, as more and more women enter the ranks of senior researchers.

As an honour of human achievement, nothing parallels the Nobel Prizes. There is much in the prize winners that people around the world draw inspiration from. And therefore, shining a spotlight on their gender (and national) composition is important. The prizes are something of a world heritage after all. People of all genders and from all parts of the world should have a shot at it.

(Karthik Venkatesh is a commissioning editor with a reputed publishing house)