- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Budget 2024-25

- Business

- Series

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- Budget 2024-25

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

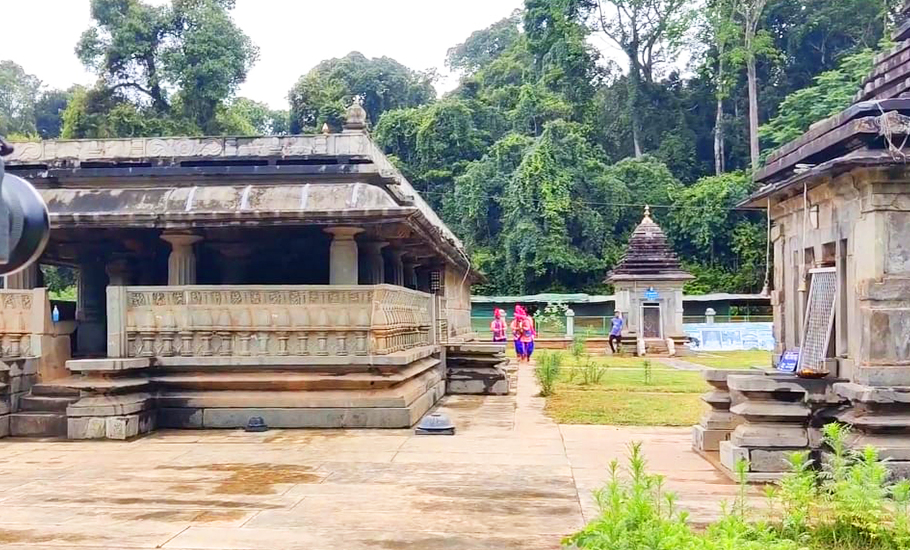

Why the temple run in Karnataka’s Hosagunda is set to get longer

In 1991, CMN Shastry, looking at business opportunities in the field of organic farming, zeroed in on a piece of farmland in Hosagunda village after looking at and rejecting several properties. Tucked in the quiet of the lush green forest area amid the Western Ghats on National Highway 206, around 60 km from Shimoga and about 16 km from Sagar in Karnataka, Shastry found the farm in Hosagunda...

In 1991, CMN Shastry, looking at business opportunities in the field of organic farming, zeroed in on a piece of farmland in Hosagunda village after looking at and rejecting several properties. Tucked in the quiet of the lush green forest area amid the Western Ghats on National Highway 206, around 60 km from Shimoga and about 16 km from Sagar in Karnataka, Shastry found the farm in Hosagunda best suited for his needs to build a farmhouse.

Right in the vicinity of Shastry’s land stood the temples of Hosagunda — neglected and dilapidated. Shastry soon took it upon himself to work on the restoration of the eight temples that had fallen upon ruins. Thus in 2001, began the work of restoring a centuries-old heritage built under the Santara dynasty which is now almost complete, drawing in a large number of tourists turning Hosagunda into a site for religious tourism.

The good news for those enjoying the temple run, and those looking forward to joining it in Hosagunda, is that the authorities have identified nine more sites for restoration work.

“We are discussing with the historians, architects and others how to restore the temples of Maramma, Prasanna Narayana, Mallikarjuna, Rameshwara, Ishwara, Kote Durgavva, Anjaneya, Bhootarayappa, and Bhootaraja to their original glory without disturbing the original architectural format or style,” 65-year-old Shastry told The Federal.

From riches to ruins

Under Jain kings, the influence of the Sanatana or Bhairarasa dynasty ran from the Malenadu region to the coastal districts of Karnataka. The kingdom had two capitals — Karkala in the coastal plains and Kalasa in the Western Ghats. Their king Veera Pandya Bhairarasa built the monolith Bahubali in Karkala.

Hosagunda, believed to be a temple city built by a family of Santara kings in 900 AD, is said to fall in Kalasa region. Researchers are yet to confirm if it was war, some natural calamity, or the vagaries of time, which ruined the temple city, but surrounded by a thick forest area, Hosagunda remained forgotten carrying within it an over 1000-year-old tale.

The word ‘Hosagunda’ literally means ‘a new locality on elevated land’. Epigraphic records of this ancient town indicate that it was newly built as a capital city and hence was named Hosagunda.

The stone inscriptions found in the temples of Hosagunda mention that it was ruled by the Santara kings. Archaeological excavations in the region show that the area was inhabited by humans even during the Iron Age. Recently unearthed inscriptions have revealed that king Bhujabala was the first ruler of the Hosagunda dynasty that ruled the region from 1110 AD till 1320 AD.

After the fall of the Hosagunda dynasty about 700 years ago, the temples are said to have fallen upon ruins because of the local population leaving the area and the entire capital township getting converted into a dense forest. It remains unclear as to why the local population deserted the area. Experts say one possible reason could have been drought.

From ruins to restoration

To undertake the revival of Hosagunda, Shastry, who had moved to the area from Puttur in Dakshina Kannada district, formed the Sri Umamaheshwara Seva Trust in 2001, along with his wife Shobha, local leader Kovi Puttappa and gram panchayat members.

The Trust is currently working on a holistic plan for the architectural and cultural revival of Hosagunda under project Pancha Ja (five Js). The project is aiming for the revival of jan (people’s cultural and religious connect), jungle (sacred grove), jal (water bodies in Hosagunda), jameen (enriching the soil, through adopting organic farming, bringing awareness amongst the villagers), janwar (a cowshed with all Indian breeds of cows).

Twenty-one years since its creation, while the Sri Umamaheshwara Seva Trust has diversified its work, it first came into existence as a charitable trust to work on the renovation of Sri Umamaheshwara Temple.

The Umamaheshwara temple, built in Kalyana Chalukya style using greenish chlorite schist stones, is spread over 2,400 sq ft. Stone inscriptions say the family of deities included Mahishamardhini and Veerabhadra, Kanchikalamma, Prasanna Narayana and Lakshmi Ganapati.

The architecture of the temple stands unique and significant. Green marble is extensively used in the flooring of the sanctum sanctorum, auditorium, patio, and amphitheatre. The pillars and wooden beams on the roof are beautifully sculpted and stand as living proof of the architectural brilliance of that time. The amphitheatre is conveniently open from three sides – east, north, and south directions for better viewing. The temple is also known as the ‘Khajuraho’ of Malnad because of the presence of many artistically sculpted figurines.

Beyond temples

Shastry’s idea wasn’t just restoring the temples. It was to restore the entire area to its pristine glory. The extended work on the nine temples and Pancha Ja are part of that plan.

With that aim, Umamaheshwara Seva Trust, environmentalists and locals made the government declare the 600 acres of forest area near the temple as Devara Kaadu (sacred grove).

The trust is contributing towards the green cause under a five-year programme which includes the plan to plant saplings of 108 different varieties. A special focus has been given to select species of plants which are on the endangered list. This programme involves people from different walks of life and school children. The forest is now attracting more birds, butterflies and wild animals enriching the wildlife, said Umesh Adiga, the technical director of Phalada Agro Foundation, who is associated with the project.

“Hosagunda is a sacred forest, rich in archaeological relics of religious and cultural significance. The staff is reintroducing native herbal species of sacred and medicinal use to create a living expression of ancient traditional medicine. Each year 108 medicinal plant species are planted throughout the forest, to connect the forest to its historical past,” Shastry told The Federal, describing the work being undertaken.

With the active support of local people, the trust has taken up various activities such as research on the area, conservation of biodiversity, botanical identification, social service and awareness-building programmes.

Expanding the scope of work

Even as the Trust was busy restoring the temple, archaeologists took up excavation work around the area and have unearthed many stone inscriptions, idols, and foundations of old shrines dating back 1000 years, Shastry said.

The restoration work started in 2001 with the cleaning of the surroundings of Sri Umamaheshwara Temple and a Narmada Banalingam, Shivling brought in from the Narmada river, being installed in the empty sanctum sanctorum. Daily prayers and rituals began with the installation of the Shivling.

As these temples in Hosagunda were built during different periods under the Santara dynasty, they are being rebuilt in the same architectural style that prevailed at the time of their original constructions resulting in Hosagunda emerging as an amalgamation of different styles of architecture.

Between 2001 and 2005, ruins, idols, and stone inscriptions, of many more shrines such as Mahishamardhini, Veerabhadhra, Kanchikalamma, Prasannanarayana, Lakshmiganapathi etc were discovered in the surroundings. In November 2005, all these idols were shifted to a makeshift temple, Balaalaya, so that complete restoration and reconstruction of each temple could take place.

Twenty-one years after Hosagunda started the journey of revival, the reconstruction of temples for all these deities where the foundation was unearthed is under progress and some of them being under completion. So far Umamaheshwar, Veerabhadra Swamy, Prasannna Ganapathi, Kanchi Kalamma and Prasanna Narayana temples along with the holy pond in the area have been restored.

“An enormous amount of effort has been put in by the Trust to bring back the glory of this ‘Temple Town’ through renovation and restoration of these temples, thereby, creating an approximation of heaven on earth,” said Girish Kovi, a local activist, who works on preservation of historical monuments.

As the temple structures and their foundations were dilapidated, there was an immediate need to restore it completely. Necessary approval was taken from the Karnataka State Department of Archaeology and an agreement to conserve the temples was signed with Sri Dharmasthala Manjunatheshwara Dharmothana Trust. The second phase of restoration began in January 2007 during which each part of the temple was serially numbered, dismantled and kept aside with special care.

The foundation of the temples had sunk due to the extended roots of the trees growing around the structure. So, the third phase concentrated on reinstating and strengthening the fragile foundations.

The restoration entered the fourth phase with the systematic and meticulous joining of broken parts. The same greenish chlorite schist stones used in the original monument were sourced to replace the missing pieces. Using the same dismantled stones, the serially numbered parts were re-joined part by part. Rebuilding an ancient monument using almost 99 per cent of the same parts from the original structure makes this restoration one of its kind in the world.

At the time of restoration, it was noticed that the dhwajasthambha (flag post) of the temple had not been installed at the time of its construction. Experts thought that this might have contributed to the destruction of the temple. As a part of the restoration process, a new 45-feet single stone dhwajasthambha was installed in the forecourt of the temples.

Holistic development

Since ancient times, the design of water storage has been an important aspect for India’s temple architecture. To fulfil this objective, a holy pond called ‘Pushkarani’, has been built as part of the temple complex.

The trust started rainwater harvesting programmes with the support of water resource management experts. As a result of the project there has been an enormous improvement in the watertable in and around the villages. This has helped the local people to harvest two crops a year.

It isn’t just civic issues that the Trust is looking after. It is also facilitating taking people back to traditional philosophy.

“The trust is also focusing on the development of the area to facilitate the study and practice of philosophy, history, yoga, ayurveda, nature, organic farming etc,” said Jyothi Hosagunda, a former member of the taluk panchayat.