- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Why the fate of Sivakasi cracker workers is clouded in smoke

At 5 o’clock on an October morning, a scrawny man in his late 30s hops onto a bus. Behind him, a young woman carrying a tiffin box calls out to wait for her. She is just in time before the bus hurtles past tiny lanes with rain puddles left by the previous night’s downpour — the air reeking of a sour odour of sulphur and sadness. As the bus stops in front of a huge iron gate,...

At 5 o’clock on an October morning, a scrawny man in his late 30s hops onto a bus. Behind him, a young woman carrying a tiffin box calls out to wait for her. She is just in time before the bus hurtles past tiny lanes with rain puddles left by the previous night’s downpour — the air reeking of a sour odour of sulphur and sadness.

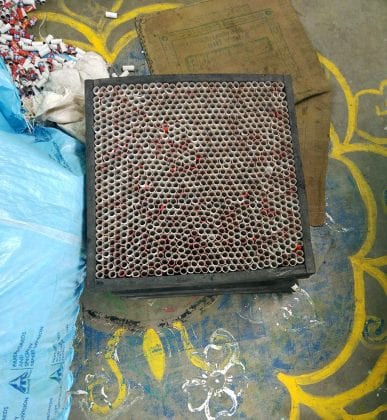

As the bus stops in front of a huge iron gate, its occupants gingerly walk inside the gate behind which tiny matchbox-like bunkers greet them. It is in these 10×10 sqft rooms that men and women work together — from dawn to dusk, in sickness and health, in life and death to produce an array of firecrackers that illuminate the Diwali skies across India.

Welcome to Sivakasi — the fireworks hub in Virudhunagar district, about 544km from Chennai. Also known for its matchbox and printing industries, the Tamil Nadu town caters to almost 90% of the country’s demand. The townscape is dotted with numerous fireworks factories — over 2,000, in addition to around 1,000 illegal units, employing an estimated four lakh people — inside which women could be seen furiously rolling cardboard paper into cubes and tubes while men, coated in aluminium dust, fill those tubes with a mix of chemicals like potassium nitrate and sulphur. Yet almost no one wears gloves or masks. These chemicals often have dangerous effects on their health, resulting in grave respiratory and skin diseases.

“Since, the work involves a lot of combustible materials, right from papers to chemicals, most factories do not have windows for these rooms and electricity connection to avoid any fire accident,” says a worker from Thayalpatti, a village about 15 kilometres from Sivakasi town.

Activists and non- profit organisations working in the area claim that the factories more often than not flout safety norms despite court warnings. The industry was earlier notorious for employing child labourers, slogging out for 10-12 hours a day. Even though factory owners claim that child labour in Sivakasi is history now, many are still engaged in the illegal units.

The birth of a fireworks hub

Originally part of Ramanathapuram district, the entire region is drought-prone and arid. A 1937 British plan to construct the Keerayan Azhagar Dam in the Western Ghats to facilitate irrigation in the region is yet to see the light of day. Left with very little livelihood opportunities, many migrated to Coimbatore, Kerala and even Sri Lanka.

While most of them ended up working in tea estates in those places, the Nadar community of toddy tappers converted to Christianity (in the early 19th century) and gained quality education.

The story goes that in 1922, two brothers from the Nadar community — P Ayya and A Shanmuga — travelled to Calcutta to work in the matchbox industry. “Since the two were mostly deployed in packing and loading matchboxes, even after months, they could not find the formula that produces the magic,” recalls an 85-year-old who runs a factory at Sivakasi.

But the brothers noticed that at the end of every day, some of the workers would enter the stock details of chemicals in a register. “So, with the help of those entries, they came to know how much chemicals were used a day and compared that with the number of matches produced on a day. This is how they cracked the formula and came back to set up a factory here,” he adds.

The dry weather and a high number of jobless people only helped them expand the industry. Soon, many others from the Nadar community in Tirunelveli and Nagercoil regions migrated and settled in and around Sivakasi, setting up cottage industries, making matchsticks. This later paved the way for Sivakasi to become the firecracker hub of India.

However, the growth of the firecracker industry led to other industries getting diminished. The printing industry employs a few hundred people, but even this industry is largely dependent on the fireworks factories since it produces wrappers, labels and boxes for crackers.

A doomed fate

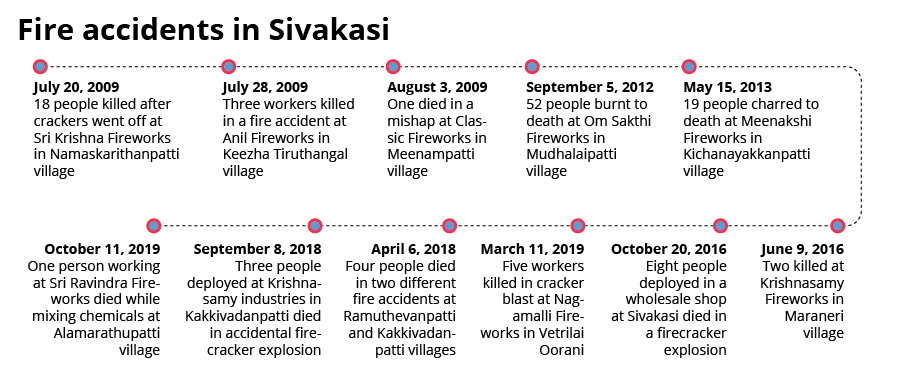

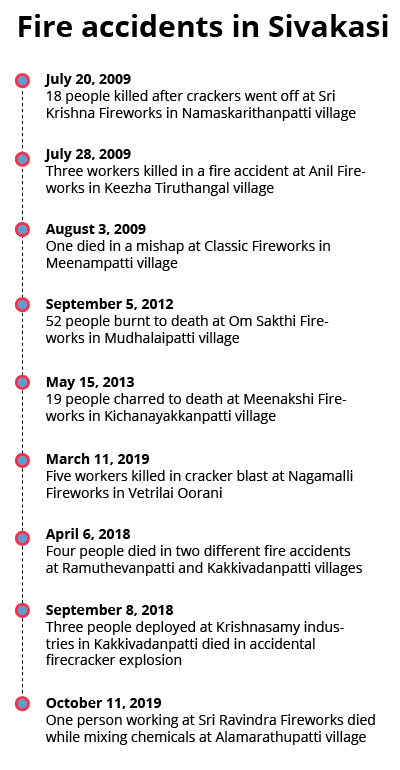

Those who work in the industry have been engaged in this business for generations. Yet, the lives of the people have not changed much. Almost every family has a painful story to tell, an unhealed scar to show — a burnt hand, a blown-off limb, a dead father, a son blown off into pieces. Deadly accidents involving fireworks are common here.

On October 11, Muthupandi, 50, of Alamarathupati village in Sivakasi died while mixing chemicals to make chakras (spinning wheels). His colleague at work, M Palaniyamma, 40, was a witness to the accident.

Palaniyamma, however, couldn’t afford to miss work the next day to mourn his friend. “We know it is not safe. It could have been me. Sometimes the crackers burst even while packing. We just don’t know what’s going to happen at any given moment but that doesn’t mean I can afford to leave my family empty-bellied,” says Palaniyamma. More so during Diwali. “It is only during Diwali that we are paid ₹30 per hour for overtime. I cannot afford to lose that money,” Palaniyamma adds.

It is not unusual to find the streets of Sivakasi deserted and soaked in an eerie silence from dawn to dusk during this season as most of the men, women and children sweat it out at the firecraker units.

The conditions in which the workers toil are unimaginable. Wages haven’t risen for years. According to some workers, they get paid ₹4.50 per 144 cardboard cones from which flower-pot crackers are made. The daily wage comes to around ₹230-400.

“We cannot demand higher wages. From last week (October 7) onwards, they have started giving a hike of 50 paisa per hour since a large number of crackers are to be made to meet the Diwali demand,” says R Robert, who earns about ₹230 per day.

But Robert is dreading what would happen after Diwali.

Dark days ahead

Robert has reasons to fear the future — one, the cracker industry usually goes dormant after Diwali for about two months every year.

“The factories will not open until January. Some factories open after Pongal in January but some remain shut till February,” says A Jagadeshwari, who rolls cones for flower-pot crackers.

“Until then, we have to manage with whatever we have or get loans from moneylenders at high interest rates,” she says without taking her eyes off her work. She then quickly dips her fingers into a bowl of glue and pastes a wrapper around a cone. “After every Diwali, we normally survive on a single meal a day for at least two months until the factories reopen.”

The other headache is the Supreme Court’s ban on conventional crackers that lead to high pollution. The ban imposed last year had forced factories to remain shut for over 100 days, leaving lakhs of workers in the lurch.

Also read: SC order for safe Diwali of no avail, Sivakasi crackers are anything but green

“During those 100 days, we could barely afford rice from ration shops. There was no money for pulses or gas cylinder. So, we all set up a common kitchen with a huge pan and would cook porridge for everyone, every day,” says A Vijayalakshmi, whose entire family works in the fireworks factory.

Since the case is still being heard by the top court, she fears there is little hope for the situation to change this year as well.

“If we face another such shutdown, kids and elderly people here would starve to death,” she adds.

The apex court has, however, allowed green crackers, with 30 per cent less emissions — according to a formula devised by the Council of Scientific Industrial Research’s (CSIR) National Environmental Engineering Research Institute (NEERI). However, the Petroleum and Explosives Safety Organisation (PESO), the regulating authority for crackers, has approved only four products for bulk production.

A PESO official tells The Federal that the new formula needs to be tested for at least one year for frictional sensitivity. Even though some companies managed to manufacture green crackers, but pending approval, most have gone back to the conventional products. And now, fearing a crackdown, many have not sent their crackers to Delhi and its neighbouring areas. (North India is believed to be the biggest consumer of firecrackers.)

“We can’t risk ourselves by sending crackers to Delhi since the Supreme Court and all top officials in the Union government reside in Delhi,” says P Ganesan, president of Tamil Nadu Fireworks and Amorces Manufacturers’ Association (TNFAMA).

With the ban in place, the threat of closure continues to loom over Sivakasi. The workers fear it will again leave them with fewer days of work and lesser cash in hand in the coming year as well.

Illegal units

Many disgruntled labourers claim the situation is a tad better away from the factories, in the villages surrounding Sivakasi. Most houses here are involved in making crackers, albeit not legally. “All these small units operating from the houses are illegal and this is an outcome of years of exploitation in the factories,” says P Kannan, who used to work in the factories earlier.

“If we work in these units, we can earn a minimum of ₹400-600 per day. But if we work in the factories, it is not possible to earn as much. Although the prices of firecrackers increased every year, our salaries never increased in the factories,” says Manikandan, a worker in an illegal cracker unit.

Also read: Fearing SC crackdown, TN firecracker makers avoid supply to Delhi

Many claim that the illegal units supply about one-third of the cracker requirement across the country.

Workers here claim that there have been no major accidents in the illegal units. It was only in the factories that such mishaps took place.

“The police and other government officials visit our [illegal] units every month and pick someone from the village and lodge a case. It is a regular affair here,” says P Maruthu, another worker.

“But can we afford to leave this work because of safety?” he asks, adding that officials turn a blind eye to factories which often flout norms and as a result most of the accidents happen there.

A PESO official denies Maruthu’s allegations. According to him, they do conduct surprise checks at factories and seal them if found flouting norms. “Every time, we raid and give them showcause notice seeking an explanation. If there is no proper explanation, we suspend their license temporarily. Hiwever, with just five PESO officials in Sivakasi, it is difficult to conduct raids in over 2,000 factories in the region,” he says.

Perhaps what unites workers on both the sides is their fate. Despite toiling for days to light up the skies above the rich and fancy, Diwali is usually a muted affair for these workers across Sivakasi.

“At most, we cook a dinner of chicken and rice on the day we get our bonus. How can we think of blowing up our hard-earned money? Such pretenses are only meant for the rich people,” Maruthu says, as his face illuminates with a burst of hearty laughter.