- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Budget 2024-25

- Business

- Series

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- Budget 2024-25

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

Where did the family doctor disappear?

Dr S Saravanan, a general physician in North Chennai, doesn’t look like any of those cool doctors from the medical dramas on Netflix. He rather resembles doctors from old Bollywood movies — the ones who would come rushing to a patient, even on a stormy night wearing a white coat and the stethoscope hanging around the neck. Of course, the brown leather briefcase in the hand meant...

Dr S Saravanan, a general physician in North Chennai, doesn’t look like any of those cool doctors from the medical dramas on Netflix. He rather resembles doctors from old Bollywood movies — the ones who would come rushing to a patient, even on a stormy night wearing a white coat and the stethoscope hanging around the neck. Of course, the brown leather briefcase in the hand meant a mini-mobile pharmacy of sorts.

However, there aren’t many family doctors like Dr Saravanan that Chennai residents can count on any longer.

When 92-year-old Saroja S was recently bedridden with a host of ailments, there wasn’t any “god-in-a-white-coat” walking in through the doors of her house. Rather, it took her children several phone calls and days to convince an ophthalmologist to come and visit her. Saroja was experiencing severe redness and pain in the eyes.

“Even though the clinic was just a few minutes away by car, it was impossible for me to go. I was already suffering from acute pain in the legs. Moreover, a few days back, I fell in the bathroom and was left with a few stitches on the head,” she says.

Like most families in cities across the country today, Saroja’s family no longer has a family doctor. They rather depend on retail clinics and speciality centres.

Where did they all go?

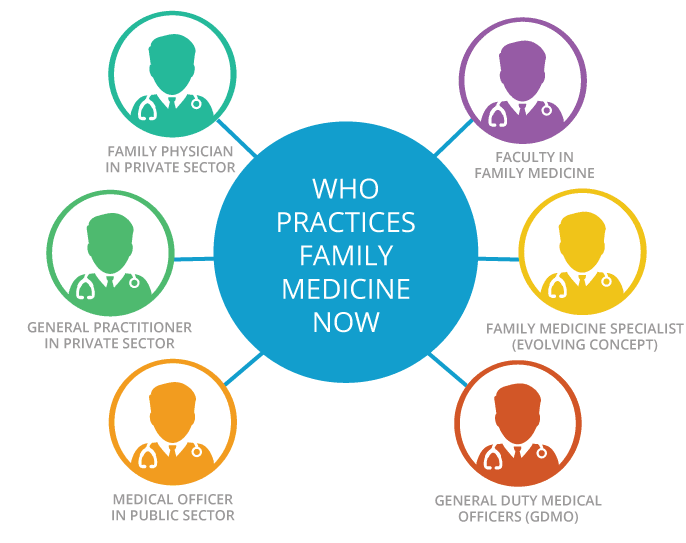

In today’s age of ‘super-speciality’ and retail clinics, there is hardly any one answer to that question. Family medicine or general practice is patient-centered, evidence-based, family-focused and problem-oriented.

There was a reason why the family doctor in films could immediately identify the problem, even if that meant a quick glance and an almost comical “ghabraiye nahin sab theek ho jayega (Don’t worry, everything will be fine)”. Okay, a bit of an exaggeration, but not entirely impossible. It’s called familiarity with a patient’s medical history, says Dr Saravanan.

When one doctor treats a person and his family for years, he/she gets to know the family’s medical history. That helps make accurate diagnosis. For example, a doctor familiar with one’s family history can easily trace symptoms of genetic diseases like cancer. So, a general practitioner (GP) can always watch for such warning signs while monitoring changes in a patient’s health over the years.

“This is not to say that specialists are not needed,” says Dr Saravanan, adding that what a GP can do in terms of diagnosis is not always true for specialists. “They tend to focus more on their own speciality and overlook other possibilities and causes of illness,” he adds.

Dr Saravanan, who has been a family doctor to several hundreds in North Chennai for nearly three decades, agrees that not many doctors can avoid the temptation of pursuing “specialisation” and remain a GP forever. The corporatisation of healthcare also has a lot to do with it, he says.

“It has changed the public’s perception of healthcare. People now run to specialists for every small and big ailment. And why not, when you can find a specialists at the click of a button and also read reviews about them and reach out to them directly?”

But things used to work differently till a few of decades ago. “Even in the early 1990s, it used to be the family doctors who would refer their patients to specialists. The preliminary diagnosis was always done by the GP because patients used to come to them first.”

In smaller cities, however, family doctors still play an important role in patients’ life.

Smrithi M, a resident of Thrissur in Kerala, relies on a homeopath for remedies to seasonal ailments. “We have also been regularly consulting an allopathy doctor for over three decades now.”

How India lost the plot

According to Dr Raman Kumar, national president of the Academy of Family Physicians of India and president World Organization of Family Doctors (South Asia Region), the rise of specialities and super specialities in the late 1970s is one of the reasons behind the disappearing family doctors.

“Ever since Independence, it used to be an MBBS graduate who would become a family doctor. Soon after speciality and super speciality degrees came to the scene, the public’s perception towards health services also changed. Interestingly, such terms — speciality and super speciality — exist only in India. You will not find them in the UK or the US,” Kumar smiles.

Specialisation, he goes on to add, assumed significance in the Western world too after the Second World War. “However, their system of medicine and healthcare has ensured that the importance of family medicine remained intact.”

Ready for revamp?

Recent data from Medical Council of India (MCI) has revealed that there is 1 doctor for every 1,668 people in India. That’s 668 patients more that the prescribed ratio by the World Health Organisation — 1 for every 1,000 people. Only six states, including TN, Kerala, Karnataka, Delhi and Goa, have the ideal ratio.

According to Dr Kumar, in order to bridge the gap across cities, ideally 25 per cent of doctors should be in family medicine or public healthcare.

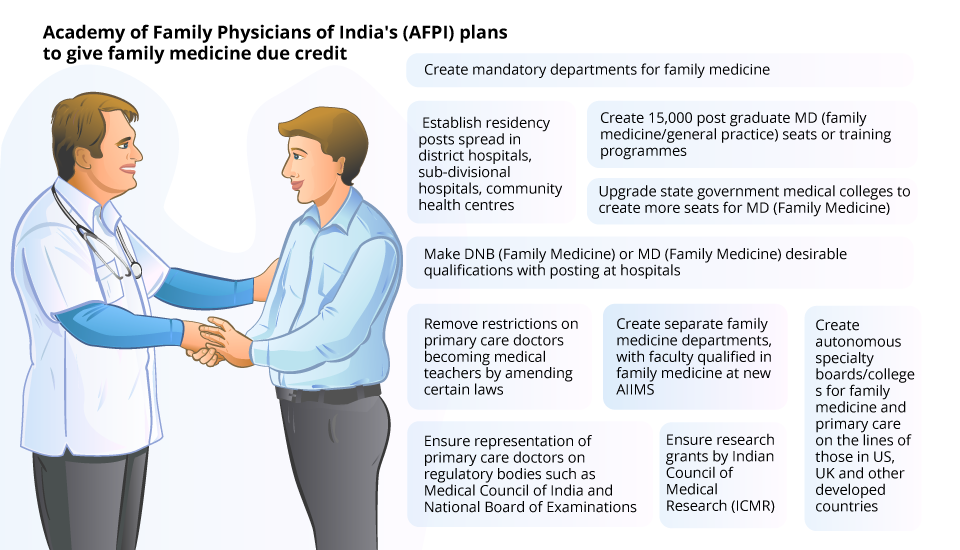

In the last decade, the Academy of Family Physicians of India (AFPI) with the help of the MCI and the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare has been trying to ensure that family medicine is given importance in the curriculum for medical education.

The MCI did not have a definition for family medicine or an undergraduate or post-graduate course until then. After much discussion, the Calicut Medical College in Kerala was the first to have a MD course in 2012. Soon, the Christian Medical College in Vellore and PGI-Chandigarh followed suit. Before this, only a Diplomate of National Board (DNB), a three-year course in Family Medicine, was available.

“We also need GPs in colleges to teach the medical students. At the moment, if you are in the primary health centres, you cannot teach in medical colleges. It is the same with family medicine and GPs,” says Dr Kumar.

From August, the curriculum for the MBBS is expected to include family medicine. But there are only seven recognised MD seats in the discipline.

The service of trained doctors, however, should also reach the peripheries, says Dr VR Rajendran, principal, Calicut Medical College. “Restricting them to medical colleges alone won’t serve the purpose. The poorest of the poor should be able to get benefit from it. CMC Vellore is focusing on that.” After all, one can’t ignore the fact that primary care saves not just money for a healthcare system but also helps unburden tertiary care.

“Last year, when Chennai was in the grip of swine flu, hospitals were chock-o-block with patients as anyone and everyone with the perceived symptoms rushed for help,” says Dr Sridevi Ananthraman, a GP, in Chennai. “Had they consulted a family doctor, they would have been put on Tami Flu dosage immediately. Patients could have avoided the hospital stays. Every case of swine flu doesn’t require to be treated in a hospital.”

For those wondering, if family medicine can ever be a sought-after practice, Dr Kumar leads by example. “I have been looking after patients in and around Ghaziabad and Greater Noida for almost a decade. But across cities, most family doctors are in their 70s now. We need to replace them in the coming decade,” he says.

According to him, there is still a long way to go before more young doctors join him.

New ventures

Many startups in cities have been trying to fill the hole by dabbling in family clinics. Santanu Chattopadhyay, who had a stint in the UK’s National Health Services, launched NationWide in Bengaluru.

Family physicians, he says, play an important role in the the UK’s healthcare system. They are also extremely trained and thoroughly prepared to respond to the needs of the public.

“Our chain of family medicine specialists include well-trained practitioners who can provide care at affordable costs. Even though there is a demand for family doctors, it’s difficult to sustain such a setup because of high rents and other costs,” he says, hoping that the trend would pick up in the next five or seven years.

Well, it’s difficult to say if Dr Chattopadhyay’s hopes will come true anytime soon. Until then, bedridden patients like Saroja will continue to wait for the “god-in-a-white-coat” to pay a home visit.