- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

Uttar Pradesh: When the regime rots and the rotten rules

The slow and sickening response of police and administration is pushing India’s most-populous state into an abyss that’s darker than ever.

Every town in Uttar Pradesh invariably has a statue of Mahatma Gandhi at its centre. Tragically enough, on Gandhi Jayanti this year (on October 2), all these venues turned into protest sites with thousands of people gathering to protest the death of a 19-year-old two weeks after she was dragged from a field and allegedly gang-raped and tortured. While there were allegations that the...

Every town in Uttar Pradesh invariably has a statue of Mahatma Gandhi at its centre. Tragically enough, on Gandhi Jayanti this year (on October 2), all these venues turned into protest sites with thousands of people gathering to protest the death of a 19-year-old two weeks after she was dragged from a field and allegedly gang-raped and tortured.

While there were allegations that the police initially did not take her case seriously, what has further inflamed the popular mood is the forceful burning of the body by the police against the family’s wishes.

Even as the outrage over the incident was peaking, another Dalit girl was raped and murdered in an equally barbaric manner in Balrampur and a minor Dalit girl was murdered in Badohi district of UP in quick succession.

The Hathras event quickly snowballed into a major political issue and the outrage has now become an all-India phenomenon. The call for resignation of Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath resounded everywhere.

In Delhi, Priyanka Gandhi participated in a high-profile prayer meeting organised by the Valmiki community, which turned into a massive social mobilisation of dalits.

Elsewhere in Jantar Mantar, Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal joined other protesting leaders such as Brinda Karat and Sitaram Yechury of the CPI(M) and civil society personalities Prashant Bhushan and Bhim Army Chief Chandrashekhar Azad Ravan. Protests were reported from many other state capitals.

Cutting off connectivity and reality

Adityanath remains in the eye of the political storm because of the continuing high-handedness of his administration. The victim’s family was almost put under house arrest and their cellphones seized. They were not even allowed to talk to the media. The Hathras village has been sealed off and no political leader or journalist is being allowed to visit the area.

But the local Rajput elite—the caste to which both Adityanath and the alleged rapists belong—were allowed to hold a panchayat in which they vehemently denied that the girl was raped.

It took 18 days for Adityanath to realise that the local police in Hathras took eight days to file an FIR and then make the first arrest in the case. In the original FIR, they mentioned only molestation and beating. Section 376-D for gang rape was included in the FIR only after nine days.

The Hathras superintendent of police, the deputy superintendent, the station house officer, a sub-inspector and a head constable have been suspended on October 2, even as the Prime Minister Narendra Modi called up Adityanath and urged prompt action, fearing a major backlash against the BJP.

In spite of this, other local police officials in Hathras and in adjacent Aligarh were still in denial mode that the girl was raped on the basis of a forensic test result they have allegedly manufactured even though the Safdarjung Hospital medical report shows injuries and “tears in her private parts”.

But the local administration was at a loss to explain why they hurriedly burnt the body of the victim at 3.00 am in the morning to preempt chances of a possible court-ordered fresh inquest.

Yogi under fire

The authoritarian temerity of the Adityanath government knew no bounds when the police manhandled Congress leader Rahul Gandhi and shoved him to the ground before arresting him and Priyanka Gandhi to prevent them from proceeding towards Hathras to meet the victim’s family. But the police could not prevent hundreds of demonstrations all over Uttar Pradesh the day after on October 2.

The damage had already been done; the wave of protests might not subside soon and even the BJP ranks have started wondering how long Adityanath would continue in office.

.@myogiadityanath जी कुछ मोहरों को सस्पेंड करने से क्या होगा? हाथरस की पीड़िता, उसके परिवार को भीषण कष्ट किसके ऑर्डर पर दिया गया? हाथरस के डीएम, एसपी के फोन रिकार्ड्स पब्लिक किए जाएँ। मुख्यमंत्रीज अपनी जिम्मेदारी से हटने की कोशिश न करें। देश देख रहा है @myogiadityanath इस्तीफा दो

— Priyanka Gandhi Vadra (@priyankagandhi) October 2, 2020

The CM himself started appearing on TV with unusual frequency and making tall claims that “those who harm the self-respect of women would be totally destroyed”. But his actions do not match this rhetoric as the Balrampur and Badhohi incidents go on to show.

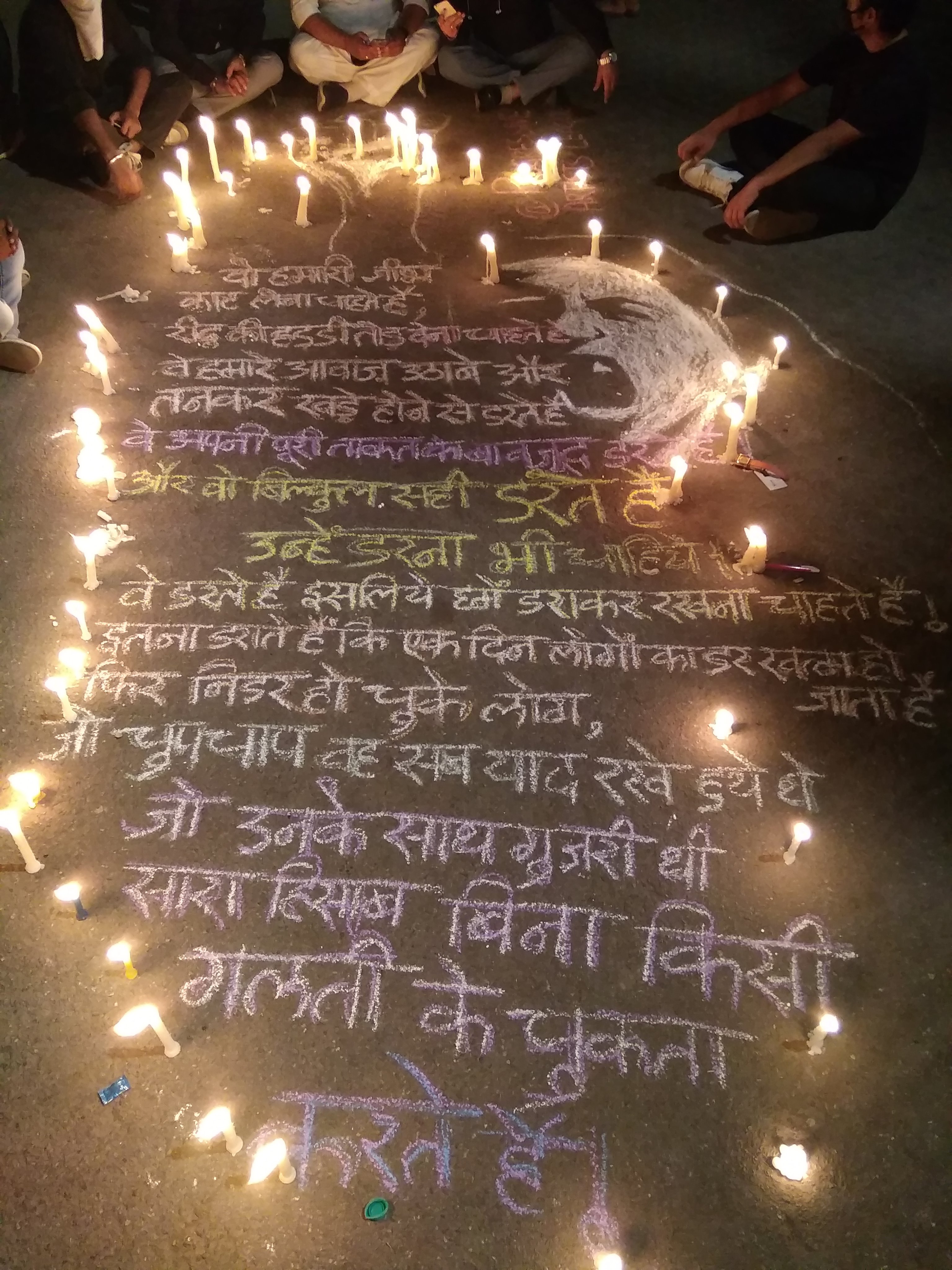

The lockdown had caused a lull in protests in Uttar Pradesh but Gandhi Jayanti brought people back to the streets. There was a surge in protests, not just by Dalit outfits but also by the mainstream opposition—especially by the Congress and, to an extent, by the workers of the Samajwadi Party and the BSP—and a whole range of otherwise dormant civil society and left groupings.

Mayawati set the political tone by calling upon the protesters to send Adityanath back to his ‘mutt’. Calls for Adityanath’s resignation have become louder. His failure to maintain law and order, especially in relative terms compared to the earlier regimes under Mayawati or even the relatively mild-mannered Akhilesh Yadav, has become the main talking point among ordinary people.

Votebank worries

Meanwhile, the BJP’s national leadership is clearly worried. From a demographic point of view, electoral importance of Dalit votes weighs on their minds. Dalit consolidation under the opposition is a nightmarish prospect for the BJP in the longer run. Only a section of Dalit votes and some Most Backward Castes (MBCs) votes can tilt the balance and can make an upper caste consolidation electorally successful in North Indian States.

If Dalits and a section of tribals and MBCs move away, that would be a losing proposition for the BJP despite the upper caste base remaining intact as seen recently in the state elections in Rajasthan and in some pockets of Madhya Pradesh.

A gory incident like the Hathras rape, happening barely 180 km away from Delhi, is bound to alter not only the local electoral caste arithmetic but will also have macro-political impact in the adjoining states. The media cannot be gagged endlessly for long.

In fact, Samajwadi Party leader Richa Singh, a former President of the Allahabad University Students Union who is now at the forefront of the protests, told The Federal that more people from other caste backgrounds participated in protests in the Poorvanchal (eastern UP) towns. The incident has also grown into an anti-BJP and anti-incumbency issue.

The bizarre dynamic

Until the late 1990s, it was Bihar that was infamous for its ‘jungle raj’. Now that dubious distinction has been snatched away by Uttar Pradesh under the BJP and Adityanath.

Strangely, western UP, which is economically more developed compared to the eastern parts of the state (the Poorvanchal region) or the Bundelkhand region, is recording an increase in incidents of atrocities on Dalits and women.

A bizarre social dynamic seen in western UP is that the more the Dalits develop economically and educationally, the more vulnerable they become politically.

The assumption that economic development in the countryside would reduce caste tensions and atrocities is clearly not true.

There is a new element added to the conventional upper caste hegemony in the village politics and local power relations. It is the sense of being rulers at the state level. ‘Our man is the CM’ is a constant refrain among the dominant caste whose shared hegemony with other upper castes has been restored by the BJP in 2017.

The mood was not so supremacist even during BJP CM Kalyan Singh’s reign in the early 1990s. After Rajnath Singh’s (BJP) tenure ended in 2002, it was a 15-year-long power drought for the upper caste elite in UP until the BJP won and Adityanath was appointed the CM in March 2017.

The impact is clearly visible in the altering equations between the village gentry and the local police officers. The local police and other administrative officials get integrated into the caste power structure and local areas resemble their fiefdoms. When the village elite feels that the police officer is “their man” who “cooperates”, they inevitably develop impunity.

Underemployment brings about some degree of lumpenisation among the restless but well-to-do upper caste youth who tend to operate in gangs. Sustaining their domination in village politics means greater dominance over the newly awakened Dalits and OBCs.

Even the traditional respect for womenfolk, especially among the middle agrarian classes and ranks, in the village community becomes a thing of the past. In all this, the Dalit women become the most vulnerable. This partly explains why educated women’s participation in the workforce in rural UP is still in single digits.

When it comes to ensuring guarantee of life and dignity to women, the state simply doesn’t exist at the grassroots. That is the reason why some administrators favour setting up of a special police force, deployed at the block level, which can work independently and directly curb atrocities on Dalits and women.

Former IPS officer SR Darapuri told The Federal, “There is a provision in the law to set up special police stations for SCs-STs similar to women police stations, but that has not been done in UP. The board under the CM to be mandatorily set up as per the SC-ST (Prevention Of Atrocities) Act, which is supposed to meet once in every six months never meets in UP.”

Following the Hathras incident, Adityanath declared the setting up of a case-specific SIT only but refused to heed the demand of the women’s groups for setting up a fast-track court.

India toughened its anti-rape laws after the Nirbhaya gang rape to fast-track rape cases and other crimes against women seven years ago. A fast-track court convicting the perpetrators of the crime within eight weeks when the rape is still fresh in the public memory can have a salutary effect on other potential rapists.

Instead, the slow and sickening response of police and administration is pushing India’s most-populous state into an abyss that’s darker than ever.