- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

The world, made to order by the US war machine

In a global system designed and controlled by the US using various means including the dollar as the sought after currency of exchange, state of the art military equipment and a huge consumer appetite to consume what the rest of the world manufactures, it seems unlikely that any country can challenge Washington’s hegemony, at least at this time.

If the saying that “the rest of the world sneezes when the United States of America catches a cold” is true, which it is, a corollary should be that “the United States scratches itself when any part of the world itches”. The audacious September 11, 2001 attack on New York and Washington was provocative in the extreme — an action that has since gotten the US into a rage that has...

If the saying that “the rest of the world sneezes when the United States of America catches a cold” is true, which it is, a corollary should be that “the United States scratches itself when any part of the world itches”.

The audacious September 11, 2001 attack on New York and Washington was provocative in the extreme — an action that has since gotten the US into a rage that has still not died down. But that is hardly a justification for its violent interventions across the Middle-East starting with Iraq in 2003.

A sympathetic world backed the US and even joined it, as part of a UN-backed coalition, during its war on Afghanistan to capture those responsible for the 9/11 attacks. But the subsequent invasion of Iraq proved that the sympathy was misplaced, as it transpired that the US was using the 9/11 attacks as an excuse to further its political agenda in the Middle-East.

Iraq president Saddam Hussein had been in the crosshairs of the US ever since the Gulf war of 1990-91. The US government rustled up a narrative projecting Saddam as a monster, spun a tale linking him with al-Qaeda chief Osama bin Laden, and without much ado, embarked on a military campaign that all but pulverised a country that had nothing to do with the 9/11 attacks on New York’s World Trade Center and the Pentagon in Washington DC.

What made the US invasion a game changer was the utter disdain with which Washington treated the rest of the world, including its allies France and Germany. Along with Russia, France said it would veto any US-sponsored resolution to invade Iraq. As a result, the US never sought a UN mandate. Instead, it launched an unilateral and arguably illegal attack on Iraq.

Now that the US had crossed the Lakshman rekha, was there any retribution? None. And, that is what indicated the arrival on the scene of a refurbished America that dared the rest of the world to act against it.

In a natural state of war

The US has gradually but steadily grown into what it is today — a war machine — starting from the time it defeated colonial Spain in Latin America in the late 19th century. The US through the 20th century, and even now, routinely interferes in countries of South America when they act against perceived Washington’s interests — typically by instigating military coup d’états, including in Guatemala (1954) and Chile (1973); fomenting low intensity warfare against the Sandinista government in Nicaragua in the early ’80s and its ever present threat against socialist Cuba. Since then, until now, it has dictated politics in that region, in what it self-proclaims as its backyard. Simply put, Latin American sovereignty ends where US interests begin.

Most recently, countries like Venezuela and Brazil that stood up to the US have found themselves in deep trouble. If Brazil’s Left-leaning governments of Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva and Dilma Rouseff had to exit ignominiously, paving the way for a right-wing pro-US dispensation, Venezuela is struggling as its Chavista government tries to fight US attempts to controversially replace President Nicolas Maduro with a Washington-friendly alternative.

Wars are second nature to the US. It has the infamous reputation of being the only nation in the world to have used the atomic bomb on another nation. In 1945, it dropped nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki that ended Japan’s fight in the Second World War. Having emerged as the key player who helped the allies win the war, the US catapulted into leadership position along with the Soviet Union, displacing the European colonialists led by Great Britain.

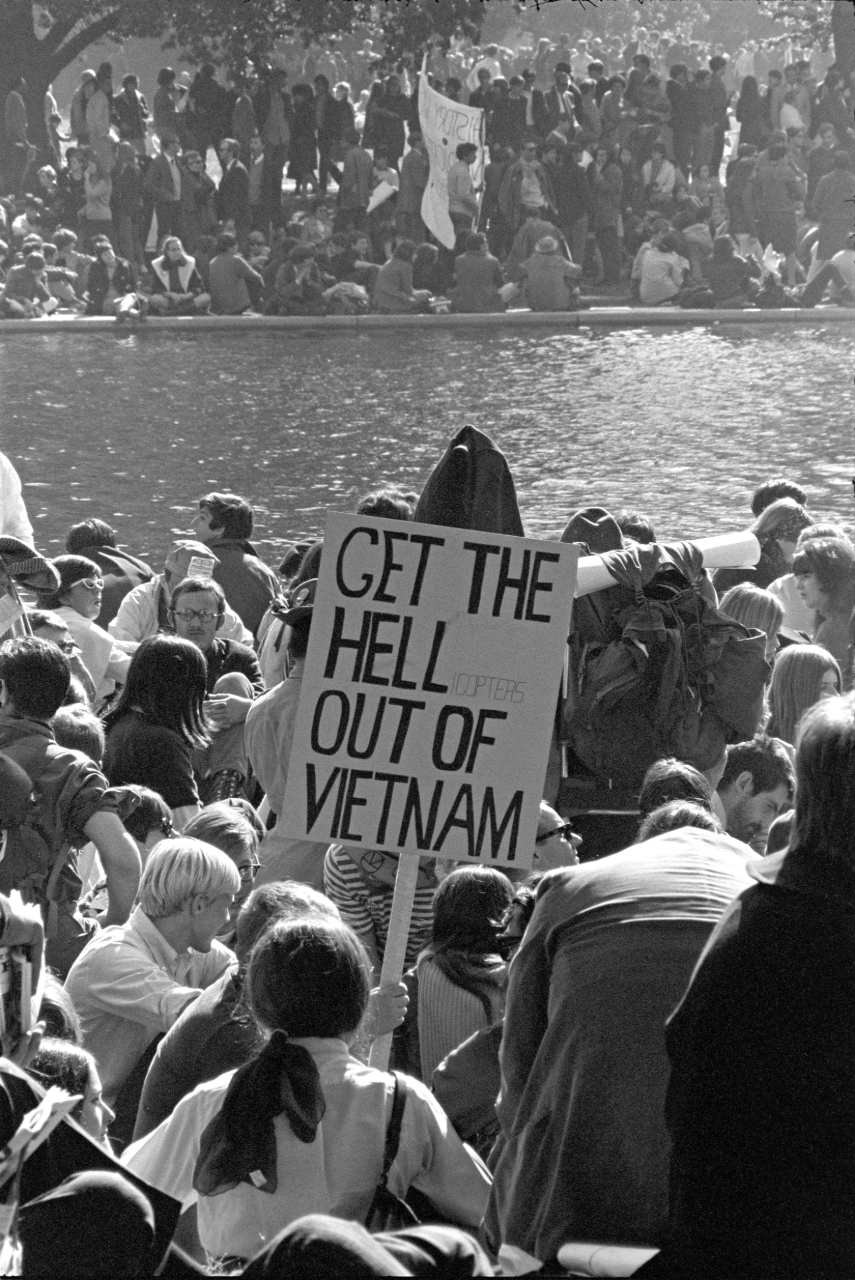

A rampaging US met its match in Vietnam in the early ’70s, defeated by a ragtag but committed resistance from the VietCong, led by the legendary Communist leader Ho Chi Minh. But that did not stop Washington from its belligerence in international politics.

In the ’80s, the US’ role in propping up the Mujahideen in Afghanistan to fight the Soviet invasion there led to unforeseen consequences. If the decade-long invasion drained out the Soviet Union, causing it to implode, a crucial outcome was the exponential rise in radical Islamic politics, including the emergence of the Taliban and its ally, the al-Qaeda, both of whom were armed and trained by the CIA.

Also read | Time timid Europe stands up for Iran

But the US benefited. The Soviet Union disintegrated in 1991, and with it, completely altered the world’s balance of power between the two big powers. Since then, the US has had a free run as the sole super, nay, a hyper power.

The Soviet breakup followed by all the cataclysmic changes in its wake did not happen in a vacuum. That was the outcome of the nearly half-a-century of Cold War that the two super powers fought, sometimes visibly and often times not. In that tug-of-war, the US prevailed and since then, it has not had enough of gorging itself on the prize it won for itself — the rest of the world.

Lack of accountability

Mind you, the word “hyper power” is not to be used loosely. Take the latest example — the assassination of top Iranian General Qassem Soleimani by the order of the US President Donald Trump. There were no secrets — Trump himself preened that he was the one behind the killing. Imagine any other nation doing something similar and the ruckus that would have followed. Only a hyper power can get away with it.

Rationalising the killing of Soleimani, the US-inspired media went all out to project him as that “shady figure” who was behind Iran’s domination in the Middle-East, cutting across Iraq, Lebanon and Syria. Western officials all but called him a terrorist, a word that is more often than not used by governments successfully to defend any killing and discredit an individual or an organisation. The fact of the matter was that Soleimani was Iran’s top military commander who slogged for his country as any senior official is expected to do.

For the US, Iran has been a red rag since 1979 when the people rose up against Washington’s ally, the erstwhile ruler Shah Reza Pahlavi, and replaced him with Ayotollah Khomeini in a violent uprising. Almost from then, until now, the two countries do not have a diplomatic relationship.

Washington did not stay quiet. Along with Saudi Arabia, which was alarmed by the Shia Islam revolution, the US instigated the then-Iraq Sunni President Saddam Hussein to launch an unprovoked attack on Iran using the ruse of a border dispute. After initial losses, Iran retaliated successfully. The resulting eight-year 1980–1988 war damaged the economies of both the countries. By then, Saddam Hussein and the US had fallen out with each other.

Iraq’s attempts to make good its economic loss by hiking oil prices was neutralised by Kuwait, a US ally, which refused to cooperate with Saddam Hussein. An angry Iraq invaded Kuwait. A US-led coalition got a great opportunity to cut Hussein down to size. The UN, prompted by the US, enforced a decade-long sanction against Iraq, weakening it considerably. Subsequently, Washington used the sympathy generated by the 9/11 attacks to invade Iraq and dislodge Hussein from power.

When the US invaded Iraq in 2003, little did it expect Baghdad’s neighbour and Washington’s bête noir, Iran to influence politics there.

The Bush administration rustled up global opposition to Iran’s peaceful nuclear programme in a calculated attempt to pressure it to stay away from Iraq. But this has not really worked as Iran is close to the government in Baghdad. Meanwhile, the Sunni Islamic State organisation emerged from the detritus of Iraq’s violence, forcing Iran and the US to tactically join hands to fight the radical group. Now that the Islamic State has been neutralised, the US is back, virtually at war with Iran, aggravated in large measure by the killing of Soleimani.

How US used Arab uprising

The churning in the Middle-East was among the reasons that led to the mass popular uprising in 2011 against authoritarian regimes in the region. Initially taken by surprise, the US quickly recovered to see how it could use the opportunity to further its interests. In alliance with its European allies, and using its clout in the United Nations, the US administration wilfully interfered with popular protests in Syria, Yemen and Libya and supporting rebels, leading to a situation where all these countries are today in turmoil. The initial largely spontaneous mass protests did not result in democracy except in Tunisia where the US did not play any role.

Egypt promised to replicate Tunisia but failed with a military ruler, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, now leading the country after a farcical presidential election voted him to power in 2014.

The US, in partnership with its British and French allies, used the mass uprising to try dislodge Syria’s President Bashar al-Assad and Libya’s Muammar Qaddafi. While Qaddafi was lynched by a mob, Bashar al-Assad has managed to survive in power. In the process, these once stable countries are in a chaotic mess leading to large scale death and destruction.

But nothing can compare with what is happening in Yemen. The US and the United Kingdom are supporting Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates with arms and money in a one-sided war to displace the Houthis who now govern the country from the Yemeni capital Sanaa. The ostensible reason for targeting the Houthis is their proximity to Iran. The incessant bombing and violence has turned the country into a humanitarian nightmare, affecting an estimated 24 million people, with no end in sight.

On the Arab street which has borne the brunt of US power, and in countries like Pakistan and Afghanistan where US drones have killed scores of innocent people, there is palpable anger against Washington.

But in a global system designed and controlled by the US using various means including the dollar as the sought after currency of exchange, state of the art military equipment and a huge consumer appetite to consume what the rest of the world manufactures, it seems unlikely that any country can challenge Washington’s hegemony, at least at this time.