- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

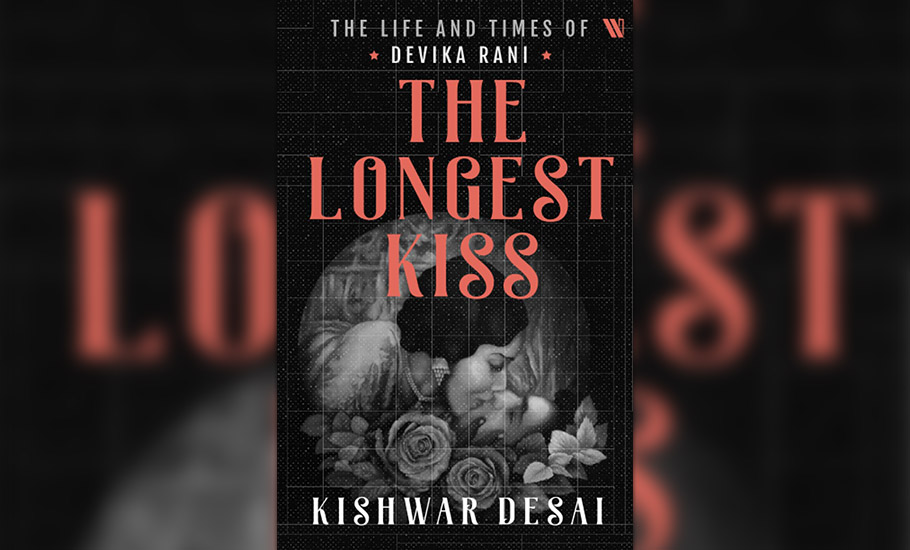

The longest kiss: How actor Devika Rani survived a Bombay of yore

When Mahatma Gandhi was busy launching the Civil Disobedience Movement against the British in India in 1930, an Indian couple in England was working overtime to introduce exotic Indian films to the international market. Himanshu Rai, a pioneer in making Indian silent films — Light of Asia and Throw of Dice — for the international market, and Devika Rani, the great-grand niece of...

When Mahatma Gandhi was busy launching the Civil Disobedience Movement against the British in India in 1930, an Indian couple in England was working overtime to introduce exotic Indian films to the international market.

Himanshu Rai, a pioneer in making Indian silent films — Light of Asia and Throw of Dice — for the international market, and Devika Rani, the great-grand niece of Rabindranath Tagore, had met and fallen in love in England. Rai, launched the ethereal looking Devika in films as a heroine and she made her debut in the talkie film, Karma (1933), two years after India’s first talkie Alam Ara (1931). The film, an Indo-British-German production, premiered in London and the critics raved about her mesmerising beauty.

The film with English dialogues had London talking but received a lukewarm response in India. Also, it created a stir as the leading lady, Devika, who plays a princess, had shared a two-minute lip-lock with her hero Himanshu Rai (who was also an actor and her husband off-screen) in the film. But all was not really well for this golden couple of early Indian cinema.

Kishwar Desai, the author of the National Award-winning book, The Longest Kiss: The Life and Times of Devika Rani, exhaustively captures the tempestuous life and times of this famous film couple. Although, the book grew out of Desai’s fascination and curiosity about the stunning actress of yesteryears, Devika Rani, who practically became a recluse later in life, the book also focuses a lot on Himanshu Rai’s character, his flamboyant lifestyle, how he could charm money out of people, especially women.

It also raises the curtain on the inner workings of the early days of the movie business in Bombay, and how it grew in pre-Independence India. For, Himanshu and Devika, bound together by a dream to professionalise Indian cinema on their return to India in 1933, went on to set up the legendary Bombay Talkies, a film studio in Malad in Mumbai. The studio was set up as a public limited company tapping wealthy industrialists of that time, including the westernised Parsis and was run on corporate lines. It launched some of India’s leading stars – Dilip Kumar, Raj Kapoor, Leela Chitnis and Madhubala. A very advanced studio of its time, European technicians, including the famous German director, Franz Osten, worked on the films churned out at Bombay Talkies.

What is fascinating for lovers of Indian cinema, alongside chronicling the rise of this phenomenal actress Devika Rani, who later became the head of Bombay Talkies (after the death of Himanshu Rai in the 1940s), The Longest Kiss also sheds light on the film industry of that time.

There are details on how early films were made, the influx of women actors in Indian cinema besides the highly educated ones like Renuka Devi and Leela Chitnis. The book mentions an episode in which Devika chides Himanshu for bringing daughters of courtesans and devadasis like the sought-after bohemian actress of her time, Hansa Wadkar, to work in Bombay Talkies. It also offers a description of how World War II affected Bombay Talkies as German technicians were arrested and later either deported or sent off to camps.

Interestingly, Devika Rani also gave India’s first blockbuster hit, Kismet (1943), which revolves around a swashbuckling thief, an anti-hero played by the inimitable Ashok Kumar (much before SRK came with his Darr in 1993), who reunites with his family. (The lost and found Manmohan Desai family saga started with this film apparently.)

What makes The Longest Kiss stand apart is that Kishwar Desai, who took 10 long years to research for the book, managed to source Devika’s personal letters, her letters from producers and others who had worked with her, documents such as minutes of board meetings of the company that ran Bombay Talkies.

Kishwar Desai, who has also penned The True Love Story Of Nargis & Sunil Dutt, among other books, is currently involved in setting up the Partition Museum in New Delhi.

In a conversation with The Federal, she says, “I managed to access Devika Rani’s letters from various archives in the country and abroad. I had documents like the 1928 job contract in which Himanshu had signed Devika as an actress to work exclusively for him.” She also scoured through old press clippings, and in the end, she had ‘two trunks loaded with Devika’s papers’.

Desai, however, does not elaborate on where she found the letters nor does the bibliography reveal much but she admits it was challenging to find authentic information on the actress. “There is so little information on her, since she was a very private person,” says Desai.

The book ends with Devika Rani’s death in Bangalore, where she had made her home with her second husband, the handsome Russian painter, Svetoslav Roerich, after leaving the world of showbiz behind in the mid-1940s.

The book does not go into the ugly controversy over the couple’s sprawling 457-acre Tataguni estate on the outskirts of Bengaluru, after her death and the dubious claimants over the property and prodigious wealth. The Karnataka government has taken over their property.

Desai’s book is kind to Devika, who was seen as “exploitative”, “calculative” and “devoid of any capacity to love”, by her contemporaries in Bombay Talkies. In The Longest Kiss, Desai, however, writes how Devika who came from a “good family” had to contend with financial insecurity from the time of her marriage, largely due to Himanshu’s flamboyant style of living. She also had to grapple with the unsavoury aftermath of his love affairs, before their marriage, which included a child born out of his relationship with a German woman.

Also, Desai claims that she chanced upon one letter that changed the narrative around Devika for her. In this letter, Devika who writes to Roerich, talks about the physical abuse she had suffered at the hands of Himanshu. “That came as a shock to me. I was amazed that someone so fragile, so beautiful, who came from the Tagore family kept quiet about the violence inflicted on her,” Desai tells The Federal.

Also, when Devika, the star actor of Bombay Talkies, ran away with a handsome actor Najam ul Hussain, her co-star in the 1935 Jawani Ki Hawa, Desai writes in her book: “The sheer physicality of filmmaking, of being in love for the camera, ignited a passion that refused to die even after the cameras stopped rolling.” Desai depicts the 28-year-old Devika as being lonely and having to live with a physically abusive husband.

Desai is unable to comprehend Devika’s dalliance with a married actor because it seems out of character and so the writer comes up with reasons on why she believes the actress embarked on a very public affair. Devika and Najam ran away to Calcutta in the middle of the shooting of Jeevan Naiyya, throwing Bombay Talkies in turmoil.

The others in the studio, like the studio’s writer Sa’adat Hassan Manto felt Devika was “exploitative” while Himanshu was seen as “hard-working and nice” and the heart and soul of Bombay Talkies. But Desai bats for Devika and says not enough credit was given to her in a male-dominated world. For, she had been an “equal partner” and struggled alongside Himanshu from the beginning, helping him set up the business by selling her jewellery, and had worked day and night for the films at Bombay Talkies doing 14 films by 1945 for the studio.

Devika went back to her husband but it was a traumatic time for both. But the show had to go on and Najam’s replacement in the film was none other than the great actor, Ashok Kumar, writes Desai. It is another matter that the actor, who resisted at first telling Himanshu that acting was for “call girls and pimps”, took up acting and his films were a money-spinner for Bombay Talkies. His Achhut Kanya, which discussed the caste system, went on to become a game-changer in Indian cinema. Desai writes in her book, quoting Manto, “The doll-like Devika and the young and innocent Ashok Kumar looked just right together on the screen.”

There’s a lot about that period and filmmaking that we learn from the book — the high taxation of raw films and studio material, the censor’s lenient attitude to lusty legs and flying kisses in foreign films but the so-called ultra-modern scenes in Indian films were banned and anti-British propaganda was strictly not allowed.

After Himanshu’s subsequent nervous breakdown, and his controversial death in 1940, Devika took over the studio and ran it with an iron hand.

Although the studio got split with two rival camps, which Desai details well, Devika managed to retain a steely hold over the studio. But she also soon lost interest in the silver screen and the movie industry. And wrote to her lover Roerich that the industry had become a complete racket with “black market money and no pure film people” just speculators and businessmen, writes Desai.

It must have been tough for Devika when her husband and her protege walked out of the studio and set up a rival one. Or, the time when old friends turned against her but she managed to survive it all and as Desai writes in the book, she was happy to leave that life behind when she met and madly fell in love with the handsome and sophisticated Roerich.

There is some risqué stuff that Desai chronicles about her passionate encounters with Roerich.

“The letters were an important part of my book. I found it intriguing that she openly ran away with an actor in those days and came back to carry on her life without losing her dignity. This woman, who did not have an MBA and had only completed schooling, held her own in board meetings. She was extremely intelligent, sharp and had even contributed to all aspects of filmmaking. All of this had been reported in a skimpy way earlier. But my book is based on documents, hard facts not speculation and I tried to understand her motives, which in my opinion make it more relevant,” says Desai, who took a year during Covid to write the book.

Devika went on to act till the ripe age of 30 years, says Desai, pointing out that the actress became more careful about her reputation and did not flaunt her affairs. There was enough gossip and mystique surrounding this beautiful actress but Desai cuts to the chase and makes it more a read based on documentary evidence. And for Desai, bagging the 2020 National Award for the Best Book on Cinema, this year, makes all the hard work worth the while.