- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Budget 2024-25

- Business

- Series

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- Budget 2024-25

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

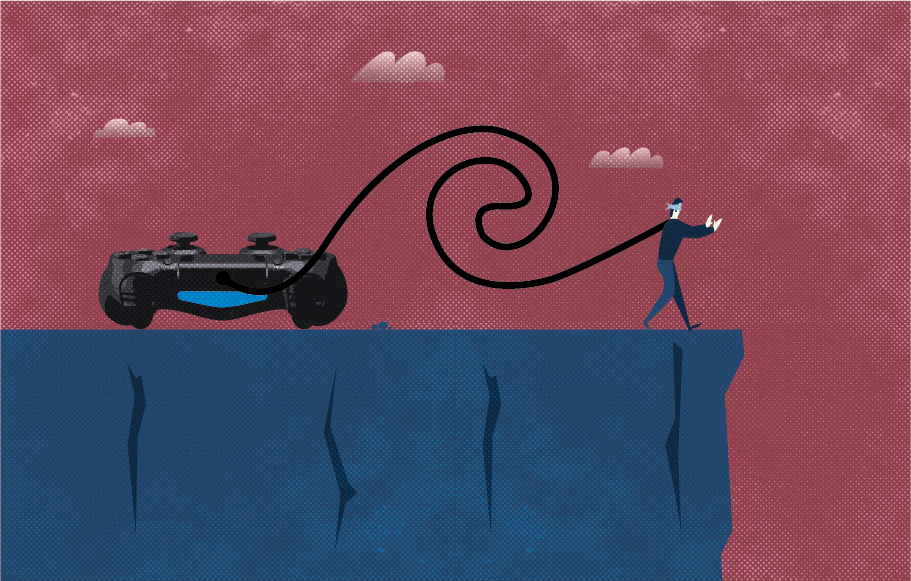

Online gaming addiction: How much is too much?

On the morning of September 9, residents of Kakati village in Karnataka’s Belagavi district woke up to murmurs about a cold-blooded murder of a 61-year-old retired policeman. Early in the morning, a neighbour heard screams coming from the house of Shekarappa Kumbar and called the police. But by the time the cops reached, Shekarappa was dead — his legs dismembered,...

On the morning of September 9, residents of Kakati village in Karnataka’s Belagavi district woke up to murmurs about a cold-blooded murder of a 61-year-old retired policeman.

Early in the morning, a neighbour heard screams coming from the house of Shekarappa Kumbar and called the police. But by the time the cops reached, Shekarappa was dead — his legs dismembered, head decapitated.

According to the police, it was his unemployed son, Raghuveer, who killed Shekarappa following a huge showdown over the 21-year-old’s ‘PUBG addiction’ the previous night.

After his father chided him for spending too much time on mobile phone playing games, an angry Raghuveer went out and threw stones at a neighbour’s house. The irked neighbour called the police, who in turn, summoned the father and son to the police station. There, Shekarappa told the cops that his son was addicted to mobile games such as PUBG (short for PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds) and Final Combat. The cops counselled the young man and let him go.

After reaching home, Raghuveer went back to playing the game, inviting another round of heated argument at night. In the wee hours, the youngster locked his mother in her room and went on to attack his father. He then took his phone and ran away from the house. Raghuveer was caught by the police the same day and remanded to judicial custody.

The incident sent shockwaves not just through Kakati, but made headlines across the nation. Although this was an extreme case, Raghuveer is not alone. Several cases of murder, suicide attempts and self-harm allegedly triggered by gaming addiction have been reported across the country.

PUBG mania

Chinese internet giant Tencent Holding’s PUBG is a widely popular multiplayer shooter game that lets users play with either friends or unknown people and offers in-app purchases using which one can customise the characters.

At each level, multiple players parachute onto a battleground and look for weapons to kill opponents. The last person or the last team to survive wins the battle.

The game was first released as an online multiplayer game for gaming consoles in 2017. Subsequently, it was made available for smartphone users in India in March 2018.

PUBG allows its players the freedom to strategise with a chosen squad. This pushes users towards a goal-oriented gaming approach, making many stick to the game for hours. Moreover, it also allows players to chat with random people across the globe, thanks to its networked approach.

“Unlike other games, you don’t get bored here as you keep inching towards a new goal every time. Also, besides my friends and family members, I can interact with strangers and make new friends,” says Rohit Kumar, 24, a gaming enthusiast who works for a tech firm in Hyderabad. Kumar, who spends nearly 30 hours a week playing PUBG, says he does not step out of his house, particularly on weekends. There are times when he’s hooked on to the game for 6-10 hours at a stretch.

Neha (second name withheld), another PUBG player, says while she had zero knowledge about guns and ammunition earlier, the game gave her insights into combat strategies and weapons. Neha can’t stop gushing about the game that makes her feel like she is part of a Hollywood action thriller.

There are millions of gamers across the world who are hooked on to PUBG like Neha and Kumar.

With more and more people showing symptoms of addiction to the game, PUBG faced severe criticism, with many calling for a clampdown against the game. The state governments of Gujarat and Tamil Nadu even considered banning the game while the Delhi Commission for Protection of Child Rights (DCPCR) issued an advisory against PUBG. What’s more, the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) banned its jawans from playing the game, revealing the stunning impact of the game’s reach.

Also read: Watching what children watch: Why cyber safety is everyone’s concern

It even caught the attention of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. During a public interaction with students and parents, a worried mother complained to Modi that her son was avoiding studies and was addicted to online games. His reaction, “Yeh PUBG-wala hai kya (Is he a PUBG gamer?)”, sent the audience into laughter.

Rise of online gaming industry

India’s gaming industry is still in its nascent stage. With the growing internet user base, increased preference for digital entertainment and the rise in Indian digital gaming developers and publishers, the industry is poised to grow from the current base of $1.4 billion to $5 billion by 2022.

Nearly 66% of urban mobile gamers are below 24 years, according to a 2017 KPMG report. However, working professionals as well as homemakers are equally likely to play online games.

Online gaming began catching up in India in the early 2000s when gaming consoles and PC games, although limited in consumption, created a niche customer base. But by the late 2000s, the rise of social media introduced online gaming to a significant population in the country, cutting across age, gender and socioeconomic groups.

Millennials started to explore games that was dominated by global publishers. But after 2010, the smartphone revolution — with increased internet penetration and availability of smart devices at low cost — led to a new wave of online gaming era.

From obsession to addiction

On the flip side, the growth in online gaming is leading to greater instances of gamers showing addictive behaviour. This, in turn, is also impacting the psychological wellbeing of their caregivers who often complain about their children losing interest in academics and decreasing social interactions.

In May, the World Health Organisation (WHO) officially recognised gaming disorder as a disease in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD 11), placing it next to gambling disorder.

Dr Manoj Kumar Sharma, Professor of Clinical Psychology at the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (Nimhans), works with technology addicts at the institute’s SHUT clinic. SHUT, short for Service for Healthy use of Technology, was started in 2014.

Speaking to The Federal, Sharma says the hospital now receives at least 10 tech addict cases every week compared to two a week in 2017.

A majority of the addiction cases, he says, involve users in the age group of 15-20 who spend almost 10-12 hours on mobile games. “They come with problems like sleeping disorder, preference for solitary confinement, decrease in outdoor activities and peer interactions, and depression.”

Video games, according to Sharma, are built to manipulate users in a way to give them a feeling of being a master, improving their self-esteem, encouraging them with monetary rewards and features that keep the players motivated and hooked to the game.

According to various reports, in general, about 4% of the online gaming population tend to show addictive behavior.

Dr Samir Parikh, director, department of mental health and behavioural sciences at Fortis Healthcare, says addiction should be defined by an impairment in daily functioning — such as studies, work, social life and health — rather than the number of hours that a person spends on games.

Many addicted gamers, he adds, face withdrawal symptoms if they quit or reduce gaming activities, pretty much like in the case of alcohol.

PUBG — China Vs India

When similar complaints were raised in China, where PUBG is quite popular, the game developer initially restricted access to minors to an hour a day. Later, as the government mounted pressure on the developer, the company restricted access to players below 13 years of age.

Also, several de-addiction centres came up in cities across China, where users had to face harsh treatment. While their internet access was taken away, some were given electroshock treatment. This led to a furore and the government came up with a regulation to control the de-addiction centres.

But unlike China, in India, the problem is largely unrecognised.

According to Dr Sharma, even as internet penetration increased, mostly people in tier-I cities such as Bengaluru, Pune, Mumbai and Hyderabad avail the help of de-addiction centres.

“There is no awareness among people living in tier-II cities and beyond. While gaming access is free and easily marketed, the information on de-addiction or de-addiction centres are not popularised.”

When asked if company restrictions like in China can be a solution, he says even if a gaming company puts out rules for users, they will ignore them.

Sharma and his colleagues at Nimhans, he adds, first help patients recognise the problem and then encourage them to reduce their craving and control the interest they have for the game.

Besides, they also counsel patients and their caretakers by doing a digital detox therapy, wherein they cut off access to all kinds of tech devices.

Dr Parikh too recommends digital detox. “Encouraging people to spend time without gadgets is something that needs to be taught to bring more awareness about gaming addiction.”

Self-moderation better than a blanket ban?

The makers of PUBG are now limiting users from accessing the game for not more than six hours a day. This could perhaps cut down on the addictive behaviour. While many politicians and academics sought a blanket ban on the game, Oliver Jones, co-founder and director of Bengaluru-based Bombay Play, begs to differ.

Self-moderation, he says, is better than a blanket ban.

Doctors at Nimhans, too, seem to agree with Jones. They believe putting a blanket ban on the use of technology might alter the behaviour of the user in a negative way. The only way to approach the problem is to bring all the stakeholders together — like parents, children, teachers and peers — and understand the cause of the patient’s boredom and isolation.

“When one watches a three-hour movie on a daily basis, do you call that an addiction? So why penalise only gaming?” asks Jones, whose company develops online games.

Also read: eSports in India is turning nerds into millionaires

Jones looks at PUBG in a different way. He says as the game lets users interact with strangers and allows them to play as a team, it teaches a lot of important life lessons like how to behave, how to be a team player and how to lead or lie low at times.

“There has to be a holistic approach to the problem. Gaming is just another form of entertainment. As a complete generation has missed out on gaming in India, it is difficult for the industry to evolve without having to educate them about the pros and cons,” he argues.