- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

Music festivals in India are slowly turning green

Every year, as the searing summer starts giving way to fall, the music scene in India begins to heat up. With more than 20 music festivals — both indoor and outdoor — taking place every year, these events are not just about popular bands and some great music. While cavorting sweatily to some rip-roaring, toe-tapping and head-banging music, fans also look forward to camping-like...

Every year, as the searing summer starts giving way to fall, the music scene in India begins to heat up. With more than 20 music festivals — both indoor and outdoor — taking place every year, these events are not just about popular bands and some great music. While cavorting sweatily to some rip-roaring, toe-tapping and head-banging music, fans also look forward to camping-like experience, sleeping in tents at exotic locations amid non-stop supply of food and drinks. The post-gig nightmare — a pile of waste at every new festival, in every new location.

However, with the growing number of music festivals, some artistes and event organisers are slowly waking up to the idea of hosting environmentally sustainable festivals and concerts.

Ricky Kej, the Bengaluru-based Grammy award-winning composer, has been making music with a message to save the environment for many years now, but to walk the talk has been tough. He says it is very difficult to make concerts and music festivals environmentally sustainable. It takes a lot of resources to pull of such events — there are generators that guzzle fuel, lighting fixtures that consume high electricity, air conditioning to deal with the heat… The waste generated is most often enormous.

While there are music festivals such as Echoes of Earth in Bengaluru that consciously push ideas of sustainability, upcycling, recycling and reuse, there is still a way to go for most music events in the country.

Onus on audience

Divya Ravichandran, who founded waste management consultancy and implementation company Skrap in 2017, says the focus of being sustainable isn’t just cleaning venue spaces and collecting waste, but to actually see what constitutes the waste generated and how it can be reduced. Ravichandran and her team at Skrap, who have worked with music festivals such as Bacardi NH7 Weekender (in Pune and Meghalaya), Magnetic Fields Festival, and Mahindra Kabira Festival in Varanasi, say that the onus is always on the largest populace — the attendees — to utilise the infrastructure set in place.

If a music festival is held in a city, there are more reliable networks of waste disposal and recycling units in place. But with destination festivals in remote areas, like Ziro in Arunachal, which are also implementing waste reduction and recycling measures, Ravichandran says they have to set up their own infrastructure. She says, “It takes us about six months to reach out to on-ground organisations, authorities and NGOs to understand what is the waste management infrastructure in place and most of these places have no waste management facilities. There are no biogas plant or recycling facilities. What we do is a lot of pre-event planning and stitching together a solution.”

They work with local workers to educate and train them about things like waste segregation and why it’s important. Much of this can and should be a task taken on by local public sanitation authorities and offices, but the ground reality is different. Beyond separating dry and wet waste, if that trash is just bundled up and going to landfills or worse, illegally dumped by a third-party contractor into rivers or mangroves, that’s not really much of a win. Ravichandran notes that when trash is cleaned, bagged and taken away from the site for the sake of maintaining a clean appearance of the event grounds, organisers are being willfully ignorant about how much trash their festival or concert generated.

Minimal impact

It is important for both artistes and events to start becoming aware of the stats and data of waste management. This may open their eyes to what can be done to reduce waste. At the end of an event they’ve worked on, Skrap creates a waste project report to give out solid numbers regarding waste generated, the type of waste, where it was sent and how much was disposable as opposed to recyclable. “That data is what speaks to people and everyone is really shocked by the amount of waste generated. Once we put forward this report, about 99 per cent of our clients work with us on a sustainable basis. A lot of these organisers we work with are very conscious and are keen on making sure they’re making minimal impact on the environment.”

Even Kej, for his part, has hired a company that audits the carbon footprint of his live performances on a quarterly basis. He says, “Right down to the minute level of printing and what kind of ink we use, ground transportation and all that — we offset that carbon footprint every quarter by tree plantation and investing in renewable energy.”

As an artiste, he says taking flights to shows is an inevitable burden for musicians who are aware of their carbon footprint, but adds that they make their own adjustments. “None of our band members — whether they are Grammy award winners or from the US or Japan — fly business class. We don’t permit it. It creates four times the carbon footprint of an economy flight. I have not flown a business class ticket in the past four years,” Kej explains.

As an artiste, he says taking flights to shows is an inevitable burden for musicians who are aware of their carbon footprint, but adds that they make their own adjustments. “None of our band members — whether they are Grammy award winners or from the US or Japan — fly business class. We don’t permit it. It creates four times the carbon footprint of an economy flight. I have not flown a business class ticket in the past four years,” Kej explains.

As a Grammy winner who plays with a fairly large ensemble of musicians (ranging from six members on stage to over 10 instrumentalists and singers), Kej says he has seen music event organisers take waste segregation and environmental sustainability a little more seriously through his music. He points to cultural festivals in Visakhapatnam and Mysuru, where he’s seen waste recycling measures in place.

While Kej’s uses audio-visual performances to talk about protecting the planet, percussionist, drummer and music producer Montry Manuel does things differently. Under the moniker of Thaalavattam, he plays entirely upcycled drums and percussion instruments. He is currently touring Europe. The drummer prefers to converse with his audience — whether local or international — once the show is done. “Sometimes, at festivals I don’t get much time, but when I come back, I conduct workshops. I still try to create awareness with the crowd,” he says. At a recent workshop in Mumbai earlier this year, Manuel collected over 600 waste items and upcycled them into various instruments.

While Echoes of Earth and several other music festivals have been putting up upcycled and recycled décor and art installations, it needs to go beyond creating aesthetic awareness. The idea of reusable cups (and incentivising buying one cup for repeated use) is one that music festivals have been slowly trying, but it is only one part of a larger solution. Ravichandran says about one edition of Weekender in Pune, “There was ₹50 off on every refill that you get with a reusable cup. Just by doing that, more than 70 per cent of the cups were reused and that cut down the trash by that much. That’s a huge number when you look at 50,000 people at an event in such a short span of time.”

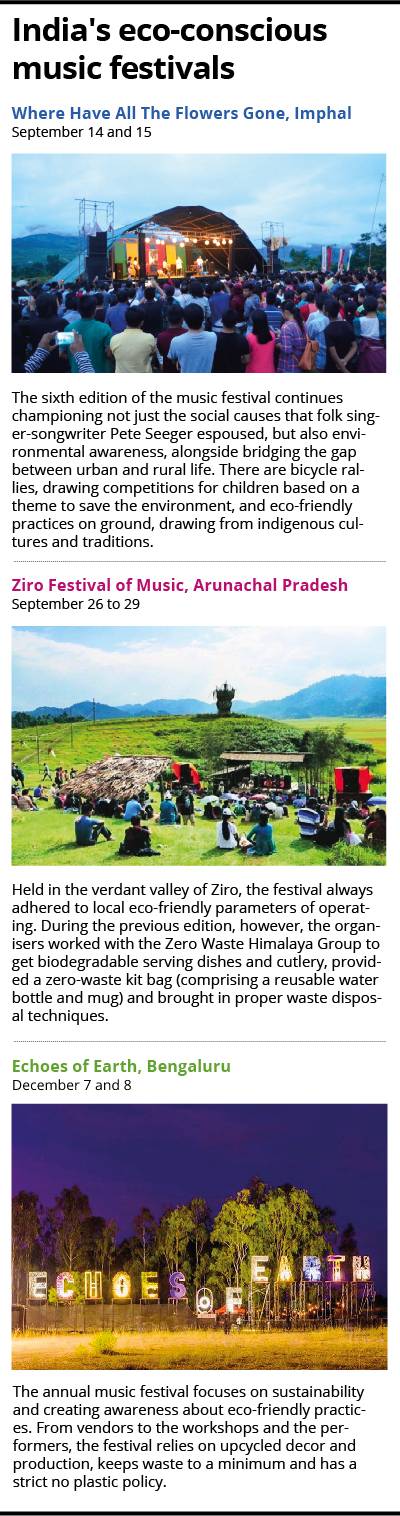

Ronid Chingangbam, frontman of Manipuri folk-rock band The Imphal Talkies and co-organiser of ‘Where Have All The Flowers Gone?’ festival, says he sees a change in how event organisers approach the ecological aspect of hosting a music festival. “There weren’t too many measures before. But at NH7 Weekender in Meghalaya in 2016, we were happy with the arrangements. It was very consciously done, keeping the place clean and controlling plastic use. With these measures in place, festival-goers learn about sustainable practices from the organising team.”

Talking about his own festival, he says that it’s a challenge to keep things eco-conscious. “Plastic has taken over all over the world. We try to tell people not to buy water bottles. We provide free reusable water bottles so that they don’t buy stuff from outside. We ask them to bring their own bottles and fill it up at our dispensers,” says Chingangbam.

The place where Chingangbam and his team host their festival is known for its local liquor, so people use plastic bottles to get alcohol. “This year, we are going to different parts of Imphal, trying to collect used beer bottles and giving them to rice beer vendors for them to use,” he explains.

Miffed residents

Despite all the efforts being made by organisers, how do locals feel about these festivals and what they are doing to their environment? After all, music festivals come and go, so do the attendees, but the residents have to deal with the aftermath. Hamsa Iyer, a Pune-based development professional who works in the field of environmental sustainability, says, “The first thing that strikes me as a completely unnecessary vice is the sale of bottled water. That adds to the concerts’ revenues, but you can find your way around it by offering good quality filtered water and selling reusable water bottles.”

NH7 Weekender, Iyer says, had reusable mugs for alcohol but they were made of aluminum. So, you won’t use them for everyday. The idea was nice, but a bit shortsighted, she adds.

“There’s a lot of packaging by food trucks that gets thrown out as well. Washrooms are the other thing — there’s still a lot of water that’s being used through unnecessary flushing. There’s also a lot of toilet paper around and it doesn’t stay too hygienic.”

So, is there a solution to it?

“I think festivals should be paperless — like without paper coupons or receipts. They could make reusable cards. They could also do day concerts rather than night ones, because it reduces electricity consumption. I know rock concerts are not necessarily conducive to day performances, it changes the entire presentation. But maybe they can evolve and create a different way of presenting music, keeping the environment in mind,” says Hamsa.

“A lot of biodiversity gets affected by loud music in the open. If you’re doing concerts on or near a breeding ground of a certain species, you’re doing a lot of damage to a particular native ecosystem. So, organisers could instead look at hosting events in a stadium.”

While it may not be possible for every organiser to employ the services of a company like Skrap, many are trying to make the best of whatever is affordable.

Even as more and more artistes are walking the talk and creating awareness, the same is missing in the audience. But Manuel is hopeful. “We have to keep educating our audience. It’s hard in our country, but people are changing.”

(Anurag Tagat is a freelance music writer.)