- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Budget 2024-25

- Business

- Series

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- Budget 2024-25

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

Jaffna library: 40 years on, memories of a violent past burn bright

When the Jaffna library was burnt down, it was not only the Tamil books that turned into ashes. The embers of hate also consumed some Sinhala Buddhist cultural assets.

Last night I dreamt Buddha was shot dead by the Police, guardians of the law. His body drenched in blood on the steps of the Jaffna Library Under cover of darkness came the ministers. “His name is not on our list, why did you kill him?” they ask angrily. “No sirs, no, there was no mistake. Without killing him it was impossible to harm a fly – Therefore…” they...

Last night

I dreamt

Buddha was shot dead

by the Police,

guardians of the law.

His body drenched in blood

on the steps

of the Jaffna Library

Under cover of darkness

came the ministers.

“His name is not on our list,

why did you kill him?”

they ask angrily.

“No sirs, no,

there was no mistake.

Without killing him

it was impossible

to harm a fly –

Therefore…” they stammered.

“Alright, then

hide the corpse.”

The ministers return.

The men in civvies

dragged the corpse

into the library.

They heaped the books

ninety thousand in all,

and lit the pyre

with the Cikalokavadda Sutta.

Thus the remains

of the Compassionate One

were burned to ashes

along with the Dhammapada.

The iconic poem, Murder, written by Sri Lankan Tamil scholar and poet Prof MA Nuhman in the aftermath of the burning down of the Jaffna Public Library (JPL) exactly 40 years ago on a June evening, is more than just a testimony to the cultural genocide by the Sri Lankan forces.

Ironically, when the Jaffna library was burnt down, it was not only the Tamil books that turned into ashes. The embers of hate also consumed some Sinhala Buddhist cultural assets. (Thus, the reference to ‘Cikalokavadda Sutta’ and ‘Dhammapada’—Buddhist scriptures—in Nuhman’s poem).

However, blinded by rage, the Sinhala nationalists perhaps never understood the inheritance of their own loss.

The poem, originally written in Tamil, was translated in English by S Pathmanathan and published in 2004.

Someone infamously said if you want to destroy an ethnicity, destroy their culture. That’s exactly what happened in the case of Jaffna Public Library. While the Sinhala majority thought they were destroying Tamil culture, the blunder continues to haunt them even after 40 years.

On the other hand, the Tamils are neither in a position to bring back the past glory of the library by increasing its patrons, nor are they ‘allowed’ to keep the memories of the arson alive (to keep the building the way it looked after the fire) in order to pass on the painful history to the next generation.

From a private collection to a public library

In 1933, when a Nazi Germany under Hitler burnt about 25,000 ‘un-German’ books—including the works of great writers such as Bertolt Brecht, Erich Maria Remarque and even Ernest Hemingway—KM Chellappah, a judicial officer and a native of Jaffna, realised the importance of books and the role they could play in educating Tamils. So, he started to lend books to eager readers from his private collection.

Gradually, he built the iconic library that according to some records was considered one of the best in Southeast Asia.

In 1959, when the library was thrown open to the public, it was spread across 15,910 square feet and was the biggest library in Sri Lanka.

Although located in a Tamil-dominated area of the country with a lot of influence that traced back to Tamil Nadu, the library was also used by the Sinhalese. Soon, it became a part of the country’s cultural heritage—something the Sinhalese people too were proud of.

Interestingly, there wasn’t any library exclusively dedicated to Sinhalese literature that could match up to JPL in terms of the latter’s collection, rarity and variety of books.

It is claimed that the people of Jaffna never bought their own copies of books since they depended on the library. Instead, they provided books to the library from their personal collection. An idol of Saraswati, the goddess of knowledge, at the entrance of the library stood testimony to the reverence of many parents in Jaffna who often used to cook Pongal (a rice dish) as a mark of gratitude to the library for helping their children pass the exams.

That fateful day

Another trait that emerged because of the library was the obsession for reading among Tamils of Jaffna. This obsession helped them get employment in government departments during the British colonial occupation. However, the dominance of Tamils in government jobs also created a rift between the Tamils and the Sinhalese that continued for years.

The angst kept simmering for years, only to explode in 1981 when the Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF) decided to contest in the District Development Council (DDC) elections.

Sri Lanka was under the rule of the United National Party then, with JR Jayewardene as the President. Jayewardene sent two of his notorious ministers—Cyril Mathew and Gamini Dissanayake—to Jaffna on May 31, 1981.

On that particular day, the TULF had taken out a rally around 8 pm. Suddenly it came to the fore that three Sinhala police officers were killed by unidentified persons. In retaliation, the police started setting fire to commercial establishments, cultural centres, etc. Around midnight, the police set fire to the Jaffna Public Library. The flames continued to burn well into next morning (June 1). It was the first cultural attack on Sri Lankan Tamils by the Sinhalese.

However, there are disputes regarding the exact date of the arson. Some say the library was set on fire on May 31, while others claim it was on June 1. Former chairman of Northern Province CVK Sivagnanam has said in a recent statement that the burning down of the JPL took place on the night of June 1, when the curfew was in effect.

“Because of the curfew, people did not get to know that the JPL was burning. It was just me who had access to the place and I took some photographs,” he said.

Those same photographs helped the media in Sri Lanka and Tamil Nadu tell the world about the arson attack. In Tamil Nadu, the photos were passed on to the media by Sri Lankan Tamil writer Maravanpulavu Satchithananthan.

To douse the fire, the Sri Lankan navy came with water tankers but were stopped by the police. The fire also engulfed the office of a local newspaper, ‘Eelanaadu’, near the library.

The next morning when the sun rose, the extent of the damage was there for everyone to see—an impressive collection of 97,000 books had turned into ashes.

The night before, Fr David, a missionary who had helped get books for the library, suffered a cardiac arrest after hearing the news of the arson attack. But the rest of the country moved on without much regret. Even the DDC elections—that sowed the seeds of conflict initially—took place as scheduled on June 4.

Failed measures

While it was an open secret as to who set the library on fire, Jayewardene announced a sum of Sri Lankan ₹20 lakh to rebuild it.

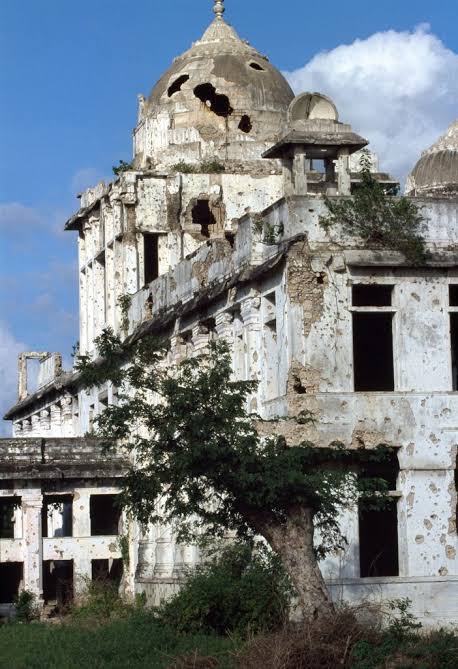

In 1984, the construction of a new building on the other side started and the JPL was opened to the public. But in 1985, when the civil war engulfed the whole of Jaffna, the new building was bombed by the Sinhalese. The Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) later used the bombed site as a hideout.

Soon, demands were raised again to rebuild the library. While doing so, the people of Jaffna asked the government to either restore the old building with all the evidence of attacks—bullet and burn marks on walls—intact or build a new library altogether on the other side. However, the burn and bullet marks had already been whitewashed by the government. As a result, the Tamils lost all the evidence. The Lankan government, on the other hand, gave the excuse that it wanted to erase the painful events and therefore, rebuild the library on the existing site itself.

“The government was not even ready to allow the library to have photos of the burnt library and bombed building inside the premises. On the contrary, the Sinhala establishments attacked by the LTTE have been turned into war monuments now,” says Somee Tharan, a Sri Lankan filmmaker. Tharan is known for his documentary, Burning Memories, on the JPL arson attack.

Books that vanished

On the fateful night, a number of rare books adorning the shelves of the Jaffna library were reduced to ashes. “The loss included extremely rare books such as the only existing copy of the Yalpana Vaipavam (a history of Jaffna), miniature editions of the Ramayana, and microfilms of the Udhaya Tharakai, a bilingual journal published by missionaries in the early 20th century,” writes archivist Sundar Ganesan in one of his articles published in Himal South Asian magazine.

Ganesan also happens to be the director of the Roja Muthiah Research Library (RMRL) in Chennai.

Besides, books written by philosopher Kalanithi Ananda Kumaraswamy, politician C Vanniyasingam, missionary Isaac Thambiah, works of literary giant ‘Satavadani’ Kathirvel Pillai all turned into ashes.

A short story titled ‘Oru Latcham Puththagangal’ (One Lakh Books), written by popular Tamil writer Sujatha, also talks about the lost treasure of JPL.

Listing out the name of some of the rare books in the library, a Sri Lankan character from the short story says, “The book Swadesa Geethangal published by poet Bharathi on his own in 1908. Its price was about two annas. The first editions of Arumuka Navalar (Sri Lanka’s famous Tamil Shaivite scholar and translator) were there. The first copy of the book Abhidhana Sinthamani published by Indian encyclopedist A Singaravelu Mudaliyar in 1899 was also there.”

“If there were one lakh books, think of how many Tamil words they would have. All those were burnt,” he laments.

The library today

Even though the JPL failed to attain its past glory, a number of books have replenished the its shelves with the help of donors from far and wide, including India (Tamil Nadu in particular) and the United States.

“When I visited the library in 2002, I had gone to Sri Lanka under the aegis of UNESCO. At that time, they lacked books in fields such as medicine. From RMRL, we have given about 3,000 unique items to JPL. However, there are no records of those items ever reaching the library,” says Sundar.

But according to Sundar, it’s RMRL that owes a huge debt to JPL.

“Roja Muthiah Chettiar, a private collector with one of the finest Tamil collections in the world, had visited the JPL before it was destroyed. The arson attack left him deeply affected and he began collecting more books to build a collection like the one that was lost.”

It is his collection, Sundar says, that forms the core of the RMRL in Chennai. “He also inspired many other private collectors who have been crucial in promoting Tamil studies and identity.”

In addition to the new Jaffna Library, Sri Lankan Tamils have created an online collection. “They have set up a website called www.noolaham.com (noolaham means library) and have scanned and uploaded all the rare books. Anyone can download the books and magazines from the website without spending a single penny,” says researcher Ariara Velan.

The website is in its 16th year now and has more than 15,000 books and magazines scanned and uploaded.

“They started this as a way of substituting the loss of JPL,” says Velan, before adding, “This library cannot be burnt.”