- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

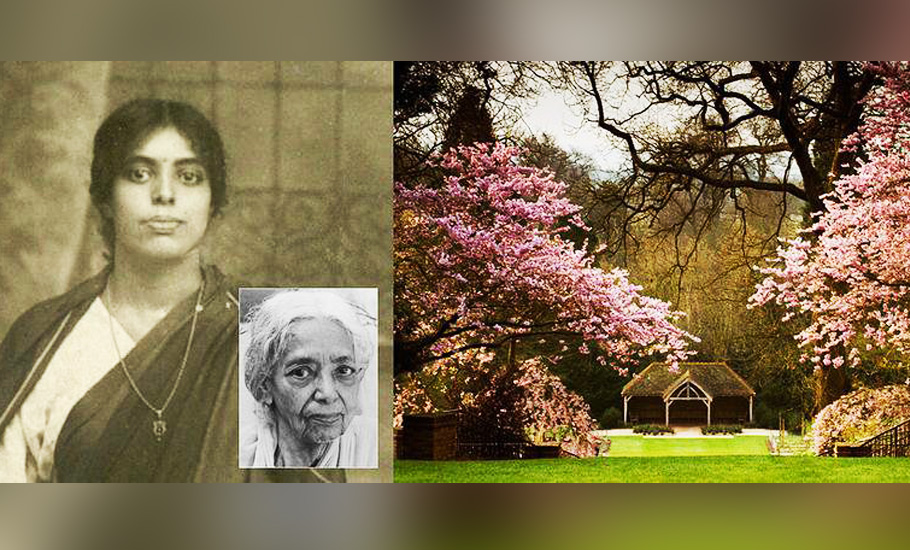

How Western Ghats shaped the life of scientist EK Janaki Ammal

Magnolia Kobus is a deciduous tree which produces cup-shaped white flowers in the spring. In the 1950s, the Royal Horticultural Society (RHS) in Wisley, England named a variety of Magnolia Kobus after EK Janaki Ammal (1897-1984), the great Indian botanist, as a tribute to her work on these plants. Called Magnolia Kobus ‘Janaki Ammal’, the trees in the Kew Gardens of RHS still produce...

Magnolia Kobus is a deciduous tree which produces cup-shaped white flowers in the spring. In the 1950s, the Royal Horticultural Society (RHS) in Wisley, England named a variety of Magnolia Kobus after EK Janaki Ammal (1897-1984), the great Indian botanist, as a tribute to her work on these plants. Called Magnolia Kobus ‘Janaki Ammal’, the trees in the Kew Gardens of RHS still produce flowers, but the nomad botanist remains an unsung heroine in her own country.

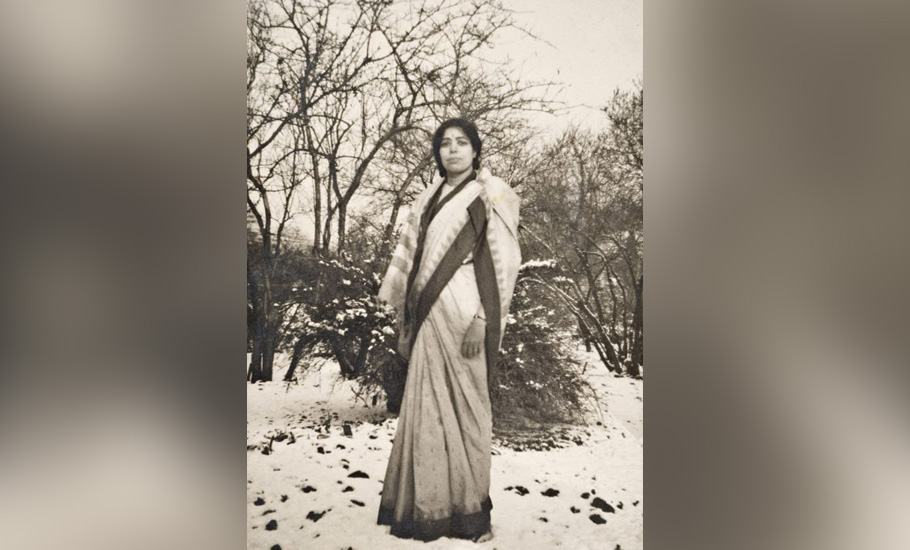

Born in 1897, Janaki grew up in a progressive Thiyya family in Kerala’s Thalassery. Using cytogenetics, agronomy, plant geography, geology, history and anthropology together with a sound knowledge of the cultural uses of plants, Janaki mapped the origin and evolution of cultivated plants across space and time. Widely travelled across the world, Janaki broke caste and gender barriers with her great scientific insights. Even though Janaki kept on travelling from one place to the other in search of plants, the Western Ghats, according to scholar Savithri Preetha Nair, remained the preferred spot in Janaki Ammal’s life.

Janaki’s working life intersected with several significant historical events. The rise of Nazi Germany and World War II, the struggle for Indian independence, the science movement, the green revolution, the dawn of environmentalism and the protest movement against a proposed hydro-electric project in the Silent Valley in the Western Ghats in the 1970s and 1980s.

“Janaki was the first to raise concern about the Western Ghats. She spoke about the importance of preserving the flora and fauna of the region even in her early years. She was also one of the first persons who said the proposed hydroelectric project would destroy the Silent Valley as a whole. However, if you look at the literature of the Silent Valley movement, you will not find Janaki in it. Her approach was different, unlike the activists. Janaki tried to mobilise support internationally. She wrote to English cytologist CD Darlington from her hospital bed. She wrote to many activists, scholars and scientists across the world. She had a quiet but powerful approach,” said Savithri Preetha Nair while speaking on ‘EK Janaki Ammal and the Western Ghats: Conceiving a project of modernization, decolonisation and conservation’ at Kerala Council for Historical Research, Pattanam Campus, in Ernakulam recently.

Preetha Nair said Janaki argued in the 1950s, that the vegetative climax of India was the dense and tall tropical evergreen forests found in the Western Ghats (and in Assam) and included among the list of objectives of the Central Botanical Laboratory of the Botanical Survey of India, which she founded, ethnobotanical research — the study of the dynamic relationships between peoples, plants and environments, from the distant past to the immediate present. The objective, however, would remain largely unaccomplished. “It would however be resumed two decades later, at the tail-end of her life, with one of its chief aims being the production of a modern and anti-colonial Hortus Malabaricus, a compendium of medicinal plants of the Western Ghats reordered from the chromosomal point of view, and based on information collected in situ from forest dwellers, who she believed were the primary interlocutors of indigenous medical knowledge,” said Preetha Nair, who is the author of the recently published Chromosome Woman, Nomad Scientist: E K Janaki Ammal, A Life 1897–1984.

Janaki’s story offers a deep familiarisation of the 20th century world. It reconstructs the world from the perspective of a pioneering and highly mobile Indian woman scientist thereby refreshing our perception of the socio-political and intellectual world of the times. Published in 1945, ‘Chromosome Atlas of Cultivated Plants’, which Janaki co-authored with CD Darlington, was considered the Bible when it came to plant sciences. With a catalogue of the chromosome numbers of more than 10,000 species of cultivated plants, the book was a result of keen and unending investigation and hard work.

Preetha Nair said it was during one of her visits to the General Library of the Natural History Museum, London in 2002 that she first found the name of Janaki Ammal in an old volume lying on the table that she was working on. “Since it was an old volume, I was a bit curious and wanted to know what was inside. It was a list of members of the Eugenics Society from its early years. Flipping through its pages, I came upon several familiar names: HG Wells, Havelock Ellis, J M Keynes, Julian Huxley, R A Fisher, Marie Stopes and then in the most unanticipated of places, an Indian one, the only name I had spotted until that point. The year was 1932 but what baffled me most was that it was a woman, from South India evidently, but a name I had never heard before: E K Janaki Ammal, Lawley Road, Coimbatore. Little did I know that this chance encounter would set me off on a humbling, even exhilarating journey,” she said.

Janaki’s father Diwan Bahadur Edavalathu Kakkad Krishnan was a subordinate judge. He was a keen horticulturist and ornithologist. It was at the Edavalath House that Krishnan built in Mahe where Janaki was born in 1897. Janaki’s mother Kuruvey Devi Amma was born to John Child Hannyngton of the Madras Civil Service (though he didn’t admit the fact). Janaki’s father’s interest and writings related to nature instilled in her a desire for science. After graduating in Botany from Chennai’s Queen Mary’s College and getting an honours degree from Presidency College, she got attracted to cytogenetics, a study of chromosomes and cell behaviour.

In 1924, the incessant rains and gusts of blustering winds wreaked havoc all over Kerala. Preetha Nair said even as the great deluge drowned most parts of the Malabar coast, a 27-year-old woman burning with desire to become an exceptional scientist, was preparing to set out on her maiden voyage. Travelling was difficult, but she somehow managed to reach Madras. Her boat had left for New York. She found a berth on the next steamer and that’s how it all began. “When she was awarded a doctorate by University of Michigan, she was the first ever Indian woman to achieve this academic milestone in botanical sciences,” she added.

Janaki obtained a fellowship to study further in University of Michigan subsequent to her joining to work in the Women’s Christian College in Chennai. Spurning marriage over work, she went on to do her DSc in the University of Michigan. In 1931, she was awarded DSc for her dissertation ‘Chromosome Studies in Nicandra Physalodes’ and was elected to Linnean Society as Fellow. Before Janaki returned to India she worked on the genetics of hybrids of saccharum (sugarcane) and sorghum (corn) with renowned biologist Cyril Darlington at John Innes Horticultural Institute near London. In 1932, she became the chairperson of the Board of Examiners in Botany and member of the Board of Studies for Natural Science and Academic Council of the University of Madras. “Janaki claimed multiple belongings as a nomad, the result of her deterritorializing wanderings (escapes) across myriad landscapes, she saw herself as a citizen of the world and as belonging to a transnational macrocosm of science. Her larger interest was in mapping on a planetary scale the migratory patterns or wanderings of plants as they occurred in the footsteps of humankind,” said Preetha Nair.

Janaki worked as sugarcane cytologist at the Sugarcane Breeding Station in Coimbatore from 1934 to 1939. According to Preetha Nair, it was a period of some remarkable observations. “Janaki devoted her first three years as sugarcane geneticist at the Imperial Sugarcane Breeding station in Coimbatore to marking scientifically controlled crosses, besides studying their chromosome behaviour at meiosis, both equally challenging and time-consuming processes that was slow science in the making. Her ingenious crosses could potentially sire a highly economic cane. The case in point being her Saccharum-Imperata hybrid, later discovered to be a highly desirable ‘stud bull’,” she said.

Janaki became the director of Central Botanical Laboratory in Lucknow in 1954. In 1957, she was elected to Indian National Science Academy. In 1959, she was elected president of the Indian Botanical Society. She served as adviser to the Biology Unit of the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre, Trombay in 1969. Janaki headed many research teams and she also took part in the international conference in India as well as abroad. In 1970, she returned to the Department of Centre for Advanced Study in Botany, University of Madras as professor Emeritus and stayed at the centre’s Field Research Laboratory in Maduravoyal till her death in 1984. “Her body was taken to her niece’s house on Harrington Road in Chennai and kept there briefly for relatives, friends and colleagues to pay their last respects. It was later consigned to flames at the Nungambakkam crematorium. It is a matter of shame that no memorial stands in her name anywhere, not even in her hometown of Thalassery, despite her being India’s foremost women scientist ever,” said Preetha Nair.