How Venkatram’s epic novel mixed humour, hallucination and sex

Tamil writer MV Venkatram's almost-autobiographical novel Kaathugal (Ears) is one of the most poignant works describing hallucination in detail.

Mahalingam, a father to seven children at the heart of MV Venkatram’s novel Kaathugal, suddenly starts hearing inexplicable noises that slowly grow into human voices. Soon, he starts seeing things, people and images of those people having sexual intercourse.

The family man, who also happens to be a writer, lives with these voices and images for years and yet manages to strike a balance between the real and the imagined world. He then seeks solace in Kandar Anuboothi—a collection of devotional hymns—and starts to believe lord Murugan is his guard—of both his body and mind.

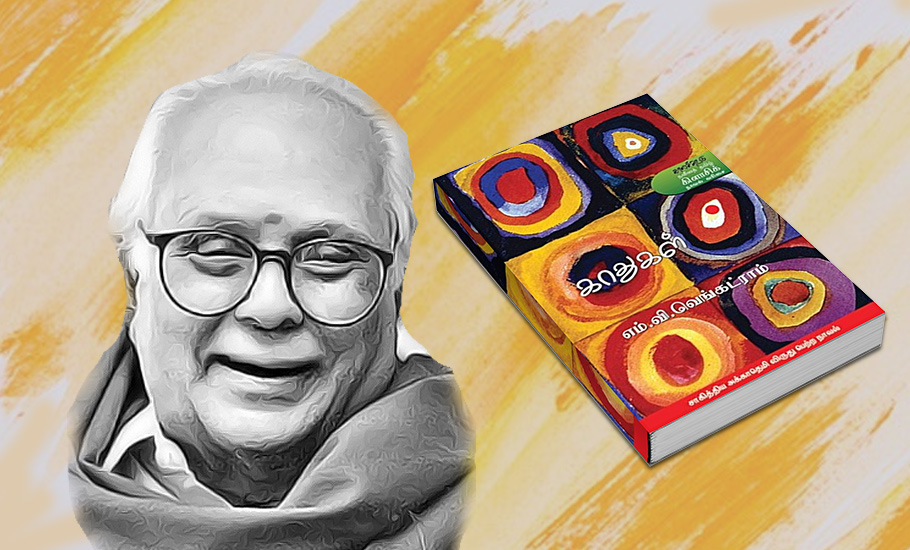

Celebrated Tamil writer MV Venkatram was 72 when he wrote Kaathugal (Tamil for ears) but not before going through similar experiences. As the novel enters the 28th year of its publication, it is worth revisiting the world of Mahalingam and ‘see and hear’ it from the vantage point of Venkatram, whose birth centenary is being celebrated this year.

Phantoms in the brain

The most well-known book of our times is Hallucinations by noted American neurologist Oliver Sacks, who recounts everyday experiences of his patients and himself that he observed in detail.

Another American author Daniel B Smith writes about his father’s torments in Muses, Madmen, and Prophets: Hearing Voices and the Borders of Sanity, and re-examines its relationship to the nature of pure faith.

Very few Indian authors have dealt with the subject in novels. Jerry Pinto’s Em and the Big Hoom is considered a popular work in this area because of its honest, humorous and empathetic telling of a woman with bipolar disorder and her family. He later edited an anthology of mental health accounts in A Book of Light.

Hindi novelist Swadesh Deepak’s Maine Mandu Nahin Dekha is yet another fascinating and insightful first-hand account into the workings of a troubled mind. It was well appreciated for its fragmented, collage-like writing, which was initially serialised in a Hindi monthly, Kathadesh, and later compiled into a book. Three years after it was published in 2003, the author walked out of his home never to return.

A pioneering work of psychology

Much before Deepak and Pinto, MV Venkatram had brought out his almost-autobiographical account in Kaathugal that won him the Sahitya Akademi award.

Published in 1992, Kaathugal is considered the first Tamil novel which discussed a psychological issue concerning auditory and visual hallucination.

Set during the Second World War, the story revolves around a writer called Maali aka Mahalingam, who one day starts to hear a hitherto unknown and inexplicable sound in his left ear. After a few days, he starts hearing other sounds in his right ear too. Gradually, the sounds turn into human voices and they start speaking of obscenity and pornography. Over time, he starts seeing hallucinatory images which are mostly of sexual acts.

When his wife Kamatchi urges him to visit a doctor, he first rejects the idea because he thinks these things happen to him due to his belief in Lord Murugan. Later, when the voices become unbearable, he decides to consult a doctor, but since he is poor he visits a saint instead, who asks him to continue believing in Murugan. So, Maali, continues to take solace in Kandar Anuboothi.

Because of the hallucinations, Maali is unable to concentrate on his work and keeps losing money and friends. Of the seven children born to him, one was stillborn. But Maali was so poor that he didn’t have money even to pay for his child’s cremation. So he buries the baby in his backyard.

Around this time, his eldest daughter falls ill and he doesn’t have the money to treat her too. But he anyway goes out to fetch a doctor. On the way, he is haunted by the voices and is unable to decide whether to go to a temple or the clinic. When he decides to go to the temple, he hears voices saying that his daughter is dead and when he decides to go to the clinic, his belief in God is questioned.

However, he keeps reciting the Kandar Anuboothi. When he reaches the clinic and asks the doctor to come with him, the doctor says he already visited the sick child half an hour back and she was alright. Heaving a sigh of relief, Maali returns home. With that, the novel ends.

One of the major strengths of the novel is the characterisation of Maali and the edge-of-the-seat detailed account of his hallucinations, which makes the readers’ heart pound—and the descriptive telling of how the hallucination affects him, gradually.

First he hears inexplicable sounds. Then the sounds of rain, blowing of conch shells, temple bells, sea waves and drum beats. Then he hears voices of animals, children, men and women. The sounds slowly engulfs his mind and body. Every time he walks, he feels a crowd is following him. Fearing he may start talking aloud because of the voices in his head, he fills his mouth with betel leaves. Then he starts to smell different odours and starts seeing images. At one point in time, he doubts whether the voices and images he hears and sees in his head are actually real, or the family and the world he lives in.

Because of hallucinations, he is unable to concentrate on what others say. So people think he has lost his hearing capacity. He thinks that this disease was handed down by his mother. In the initial days, he tries to clear the voices by pouring asafoetida dissolvent, warm oil and hydrogen peroxide in his ears, but to no avail.

Autobiographical in nature

Venkatram, it is believed, was able to portray the imagined world so accurately since he too suffered from hallucinations. “Within 160 pages, Venkatram was able to portray his two decades of life. In his later life, he lost his hearing capacity. For a man who heard voices continuously for 20 years, the hearing loss could have given him a respite. He used to say that he writes to find himself. That’s true with this novel,” says well-known poet Sankarramasubramanian.

Venkatram’s family life finds many reflections in the book. Like the fact that he and his wife Rukmani, whom he married when he was 19, had 14 children, out of which only four sons and three daughters survived.

Venkatram had a knack for writing short stories from a very young age. He was 16 when his first short story titled ‘Chittukuruvi’ was published in Manikkodi, a well-known literary magazine of that time. Thereafter, he published 18 of his stories in that magazine and was among the lot of writers who later became known as ‘Manikkodi kaala eluthaalargal’ (writers of Manikkodi time).

Born to Veeraiyan and Seethai Ammal on May 18, 1920, Venkatram was later adopted by Seethai’s brother Venkatachalam and his wife Saraswathi, since all the 10 children born to the couple had died.

Being well-versed in Tamil, English and Sourashtrian languages, Venkatram used to translate too. His lover for the literary world meant he had to lose out on his silk saree business. So he started his own magazine called Theynee (Honey bee) in 1948, inspired by the English magazine, The Bee.

While he paid his writers well, this affected him financially and soon he found himself agreeing to a contract to write a series of 40 books on freedom fighters titled, Naattukku Uzhaitha Nallavar, for Palaniappa Brothers publications.

In his lifetime, Venkatram wrote seven novels, six novellas, hundreds of short stories and two essay collections. In many other publications, he used the pseudonym ‘Vikraga Vinaasan’. He died on January 14, 2000.

“The life of MVV has many layers. In his birth home, he faced poverty. In his adopted family, he lived a rich life. He started writing at 13 and published the first story at 16. He bore losses while running his magazine. Then he became a rowdy, having some mercenaries working under him for some time. Then he joined the Congress and lost the election for councillor post. He was loved by many women at one time” says Ravi Subramaniyan, a poet, who along with two others have collected hitherto unpublished short stories of Venkatram to be published soon.

In his later days, Venkatram used to write for 8 hours at a stretch. Because of that, he had ‘writer’s cramp’, says Ravi Subramaniyan.

Distanced from personal life

The beauty of Kaathugal is that it does not prescribe any solutions to Maali to come out of his problems, says Sankarramasubramanian.

“Instead it teaches the readers to accept what comes to you. When writers of his time were speaking about Sigmund Freud and Nietzsche, Venkatram never tried to give any meaning to his hallucinations,” he says.

In some places, he adds, instead of feeling sad, the reader can’t help laughing. Venkatram’s ability to distance himself from the character Maali, in facing the problems, is where the novel stands out.

Author and Ayurveda practitioner Sunil Krishnan says Venkatram wrote this novel as a witness to his madness.

“Through this novel, Venkatram has discussed schizophrenia and split personality disorders. Generally, the western psychology and psychiatry sees the Indian mindset of ‘renunciation’ as madness. But that need not be. The writer uses dark humour to explain his ordeals.”

In the novel, the writer portrays ‘Tamas Guna’ as Goddess Kali. That turned out to be a hallucination.

Venkatram used to believe, Krishnan goes on to add, that one needs new imagery to beat the old one. “That’s why he held on to Murugan. He was trying to say that he could defeat the imagined Kali with the help of Murugan.”