- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

How Urus from Kerala’s Beypore sail to Qatar

As you climb through a makeshift wooden ladder to reach the deck of an unfinished 150-foot-long ‘Uru’ (wooden dhow or fat boat), you see a man in white shirt and dhoti busy giving final touches to a miniature boat out there. Remains of dried wood glue and sawdust add dark patches to his palms. He has to finish the work fast and send it to a businessman in Doha, Qatar. Interestingly,...

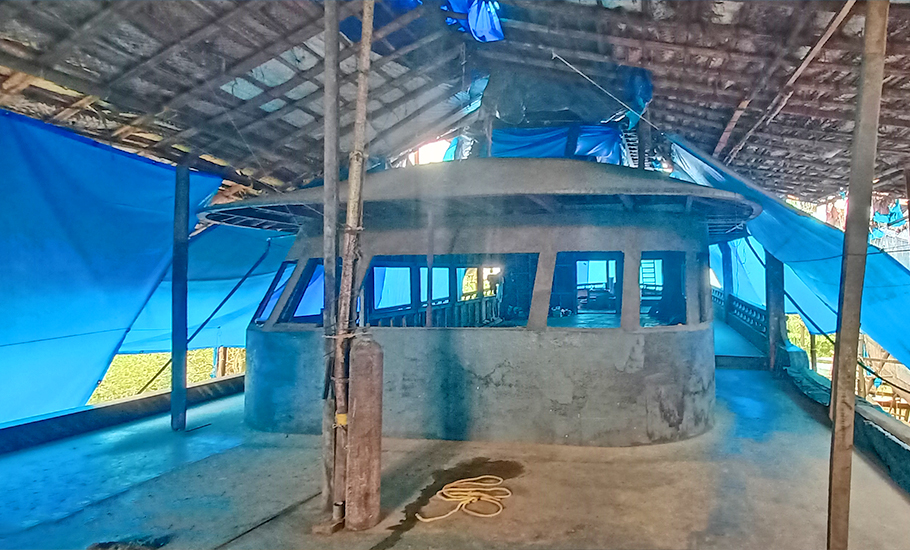

As you climb through a makeshift wooden ladder to reach the deck of an unfinished 150-foot-long ‘Uru’ (wooden dhow or fat boat), you see a man in white shirt and dhoti busy giving final touches to a miniature boat out there. Remains of dried wood glue and sawdust add dark patches to his palms. He has to finish the work fast and send it to a businessman in Doha, Qatar.

Interestingly, senior carpenter Sathyan Edathodi is the creator of the miniature boat as well as the Uru. He makes the miniature one to meet his initial expenses, the big one for saving. Even though his team started working on the big Uru in 2018, natural calamities like the flood and the pandemic-induced lockdown brought in stumbling blocks. Meanwhile, the work on another Uru is also pending. Since most of the ‘Urus’ are being made for the rich families in Qatar, there was a delay in releasing the funds due to the pandemic-imposed lockdown. For Sathyan, size doesn’t matter, but survival.

Beypore, a coastal town 11 km from Kerala’s Kozhikode (Calicut), has been an active centre of navigation and ship-building since the mediaeval period. Situated on the northern bank of the estuary of the Chaliyar River, the place was famous for making Uru, which was suitable for the Indian Ocean. Italian traveller Ludovico di Varthema who visited many areas of the Indian Ocean in the 16th century had given a clear account of the characteristic features of the vessels made in Calicut off the West Coast of India.

Scholars have documented that this coastal town once produced a large number of boats for Arab countries. Interestingly, the tradition of boat-building prevails even today.

Sathyan Edathodi, who has been making the Urus for the last 35 years, said they make Urus mainly for the rich families in Qatar. They don’t make cargo and fishing boats these days. Why? The Urus are made of wood (preferably teak), not fibre. “It means a lot of money and time,” said Sathyan.

There was another unfinished one lying adjacent to it. Both the Urus are being made for a businessman in Doha. Once the basic work is over, the Uru will be taken to Dubai port where the luxury work will be done. An 150-foot Uru costs at least Rs 7 crore, as it is made of teak wood. “Many Arab families own Urus. It is like we buy a luxury car. If a guest comes, they can’t take them to places like Ooty or Mysore. They can take them to sea only. They use the Urus mainly for their sea outings,” he said.

Once a fabulous place for boat-building, Beypore today lacks infrastructure to continue the traditional craftsmanship. “Our previous place was taken over by sea. We shifted to this site in 2011 and we have made eight Urus so far. They have been sent to the Gulf countries, mainly to Qatar. We have the record of making the Uru of 200-foot-long ‘seven’ years ago. But we don’t get any support from the government or other organisations to continue this traditional job,” said Sathyan, a native of Beypore.

After learning the basics from his father, a known Uru-maker, Sathyan went to Qatar in the 1990s, where he got trained under a Lebanese boat-maker. Bepore used to make all kinds of boats till the 1980s, but Urus were a favourite of the Arabs, who have been conducting trade with the Western Coast of India since the mediaeval period.

Why do the Arabs prefer the Urus from Beypore? The availability of good quality teak is the main reason. The outside portion of the Uru is made of premium teak wood, while local woods are used in the interiors of it. The Malabar teak was popular, a reason why Arabs preferred Urus from Beypore and it became a hub of Uru-making.

Beypore is located on the northern bank of the estuary of the Chaliyar River, which is also known as Beypore or Nilambur River. The river originates in the Western Ghats and flows through Malappuram district for about 169 km to join the Arabian Sea near Beypore. The Nilambur valley is famous for teak forests. “Beypore was well-known for timber trade and traditional boat building and it has been reported that large boats for Arab countries were built at this town. Beypore was a major port from the late mediaeval period and it is located very close to Feroke which acted as the headquarters of Tipu Sultan. It was also a centre of Odayis and Khalasis, who were involved in boat-building activities, at least from the late mediaeval period,” wrote V Selvakumar in a research paper titled ‘A Stone Anchor from Beypore, Kerala, West Coast of India,’ published in ‘Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology’.

Kerala, according to Selvakumar, possesses rich maritime traditions dating back to the Early Historic period. A few types of traditional watercraft developed indigenously and some are influenced by external contacts.

“The Beypore Uru design is considered to be influenced by West Asian traditions,” he said, quoting James Hornell, an expert on ancient watercraft. “According to Hornell, ‘the Malayali adheres to the indigenous dugout design, the Arab type is largely built at those Mappilla centres, where the strain of Arab blood is appreciable, as for example at Calicut, Beypore and Ponnani.’ However, this categorisation cannot be extended to the past. It needs to be researched carefully to understand if the Beypore design is entirely non-local or if any of the early Indian elements were incorporated in it. Craftsmen of Beypore perhaps built boats of different types for various markets; and hence they could have copied and experimented with a combination of technologies,” he said.

S Sreedharan, a carpenter in Beypore, said a strict methodology is being followed in the making of Uru. “We need to follow the measures properly to make an Uru. It needs errorless calculation and planning. A slight error will spoil the whole project, so we have to be extremely careful,” said the 65-year-old, who has been part of making Urus in Beypore since he started working as a junior carpenter at the age of 17. “It (Uru-making) is teamwork. A single person can’t claim the credit,” he added.

Even though there are expert carpenters who can make Urus in Beypore, the place lacks facilities for the maintenance of this watercraft. “Once the Uru is taken to the water, we can’t take it back. We can only make Urus and send it. We don’t have a place for their maintenance and that’s a serious issue,” said Sathyan, who happened to do the maintenance work of a 60-year-old Uru made in Beypore when he was working in Doha in the late 1990s. “It shows how strong the Urus made in Beypore were. I did the maintenance work of that Uru more than two decades ago, which means it is more than 80 years old now. I recently heard that it is still running. We calculated the age of that Uru based on the records found in it. It was a great experience,” he added.

In 2022, the District Tourism Promotion Council, Kozhikode applied for a Geographical Indication (GI) tag for the Beypore Uru, a symbol of the maritime trade and exchange of Kerala with the Arab countries. However, the Uru-makers like Sathyan and Sreedharan, want some strong involvement of the state government or other organisations to continue the job.

“If 25 people work continuously for eight hours, we can make an Uru in 15 months. Today, we lack sponsors. Earlier, there were people in Calicut who placed orders for Urus and then sold them to Arab merchants. But today, we have to find our own buyers. I am using the same contacts that I developed when I was in Qatar for selling the Urus that we make in Beypore,” said Sathyan. “Many senior carpenters have left the job due to inconsistency in the field. The orders have come down, but we haven’t lost hope. If the state government can come forward and help us, we will be able to continue this craftsmanship,” he added.