- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Budget 2024-25

- Business

- Series

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- Budget 2024-25

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

How the Soviet-US Cold War played out on the chessboard

“Too many times, people don’t try their best. They don’t have the keen spirit; the winning spirit. And once you make it you’ve got to guard your reputation–every day go in like an unknown to prove yourself. That’s why I don’t clown around. I don’t believe in wasting time. My goal is to win the World Chess Championship; to beat the Russians. I take this very...

“Too many times, people don’t try their best. They don’t have the keen spirit; the winning spirit. And once you make it you’ve got to guard your reputation–every day go in like an unknown to prove yourself. That’s why I don’t clown around. I don’t believe in wasting time. My goal is to win the World Chess Championship; to beat the Russians. I take this very seriously.”

—Bobby Fischer in the prelude to the Chess World Championship in 1972

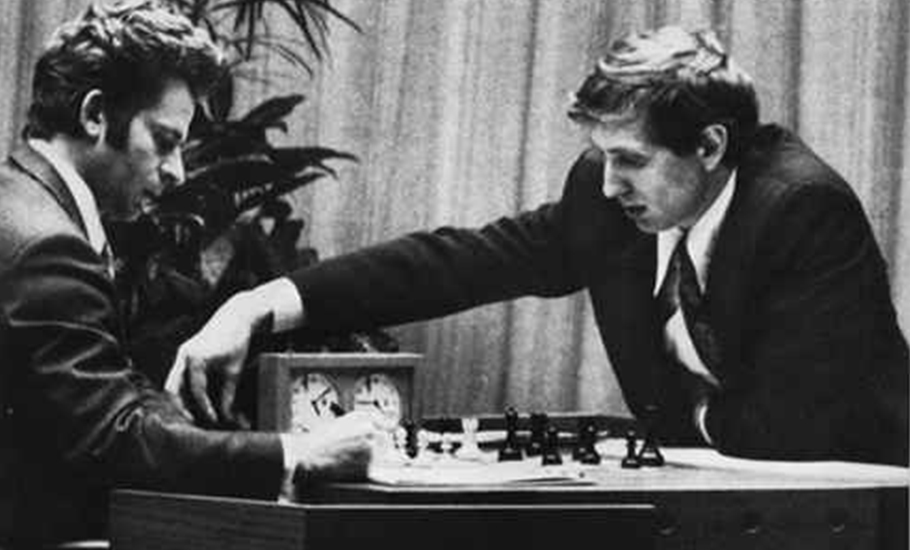

For the 24 years between 1948 and 1972, Russia, then officially under the banner of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, commonly known as the Soviet Union, dominated global chess and held an undisputed monopoly over the title of world champion. However, all of that changed in the August of 1972, when American-born (and now deceased) chess legend Bobby Fischer defeated the defending Russian Grandmaster Boris Spassky at the iconic World Chess Championship final in Iceland’s Reykjavík.

The face-off between the two has been touted as the ‘match of the century’ for multiple reasons. For one, it took place against the backdrop of the Cold War between the USA and Soviet Union and their respective allies, albeit during the detente period of the war when geopolitical tensions between the two were relatively easing up. Irrespective, the prelude to the highly anticipated and heavily publicised showdown, which took place amid an unusual public interest from both nations, was also marred by controversy. In fact, for a while it looked like the match might not take place at all.

Fischer (29) made a slew of demands before the match; that in addition to the prize fund of $125,000, which was to be shared 5/8:3/8 between the winner and loser respectively, players also receive 30 per cent of box-office collections as well as 30 per cent of proceeds from film and television rights. When his demands were not met, Fischer, who has been described as “erratic” throughout his chess career, did not show up in Iceland for the opening ceremony of the tournament in July. He finally flew to Iceland and agreed to play after much persuasion—which included a phone call from then-US national security adviser Henry Kissinger.

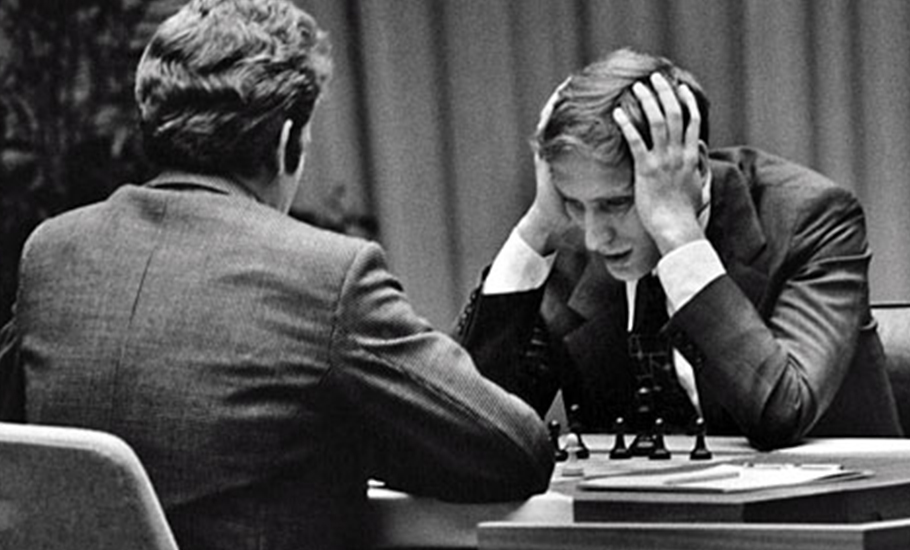

However, in his first game against Spassky, he drastically miscalculated a move that left his bishop trapped and cost him heavily, leaving Fischer holding his head in his hands. He went on to forfeit his second game without even appearing in the hall where the match was taking place, after his demand to remove all cameras from there was denied. Fischer was left trailing 0-2.

Both Spassky and Fischer faced immense political pressure to win. After all, no American had won the World Championship ever since the first champion, Wilhelm Steinitz, who became a naturalised American citizen in 1888. However, Fischer was more vocal in his dissent about America as compared to Spassky and the Soviet Union. “Americans want to plunk in front of a TV and don’t want to open a book…,” he said.

Earlier this month marked Fischer’s birth anniversary. And nothing describes the eccentric, crazy uncle of the chess world as well as looking back at his title win against Spassky in best-of-24 games at the World Chess Championship of 1972 which he went on to win 12.5–8.5. Russia was left red-faced then after their 24-year-dominance came to an end—the same way it has been left embarrassed now after a majority of chess grandmasters, including those from Russia, have condemned its invasion of Ukraine, and with FIDE, the world governing body for chess, revoking Moscow from hosting the prestigious Chess olympiad later this year.

On Monday, the FIDE Ethics and Disciplinary Commission (EDC) reached a verdict relating to the public statements made by Russian grandmasters Sergey Karjakin and Sergei Shipov, both of whom have publicly stood behind Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Karjakin has been found guilty of breach of the FIDE Code of Ethics 2.2.10 and has been sanctioned to a worldwide ban of six months from participating as a player in any FIDE-rated chess competition from March 21 onwards. Shipov has not been found guilty of breach of the code, which reads: “Disciplinary action in accordance with this Code of Ethics will be taken in cases of occurrences which cause the game of chess, FIDE, or its federations to appear in an unjustifiable, unfavourable light and in this way damages its reputation.”

After trailing 0-2 to Spassky, Fischer went on to win the third game, draw the next, and win the fifth, leaving the duo tied with 2½ points each. However, Fischer’s true brilliance was on full display in game six, when he played the Queen’s Gambit Declined opening against Spassky—a move that he had previously condemned. The Russian grandmaster, who was playing with the Black pieces, played his signature Tartakower’s Defence which he had reportedly never lost up until then. Such was Fischer’s creativity during this match that Spassky himself got up and joined the audience in applauding Fischer’s win. Fischer took the lead for the first time in the match (3½–2½).

“I think this match (between Fischer and Spassky) went on to make chess a global sport back then,” five-time World Chess champion Viswanathan Anand tells The Federal. “Fischer was someone who was not a product of the system and completely self-made. On top of that, he had this lack of conformity…he wasn’t your typical, quiet chess player. His tantrums and demands (during the 1972 championship) against the backdrop of the Cold War is very similar to India-Pakistan matches. That is why this is considered the ‘match of the century’ in terms of impact. Never before had a match been followed so widely. People across countries took notice of chess for the first time.”

“It was also a blow for the (communist) party and even for the common people in Russia; they may have liked or disliked the party but I think they assumed that they were better at chess than other countries, which made Spassky’s defeat hard to swallow,” he adds.”

“I am lucky to have watched game six on a non-computerised platform and therefore I remember the impact it had on me,” he said. “It really inspired me to want to play the game at the level. It was aesthetically a very high-level game. The relevance was that he (Fischer) took the lead in the match. It (game 6) also ties in nicely with today’s era because of the Queen’s Gambit series.”

Anand says that he thinks that individual players from Russia admired and even liked Fischer, but were “forced to toe the line by the (communist) party”. He said: “I am sure that inside, their feelings were quite different because sportsmen who don’t constantly go into a box are generally liked…but on top of that you had the Soviet Union and US rivalry, and he was an American doing battle…the impact would be comparable if a Soviet Union player played baseball to a phenomenal level, even though baseball is a team game. Chess was one of the treasured sports of the Soviet Union and he was a brash American taking them on. Politicians and celebrities also got involved…”

Some chess commentators have also argued that the erratic demands made by Fischer before and during the tournament were a part of his strategy to psyche out Spassky, while others argue that this was the moment that Fischer had worked all his life for—to be the World Chess Champion—and that he wanted it to be perfect. “It has been said Fischer’s demands improved lives for every other chess player and that thanks to his demands, tournament organisers started taking requests made by chess players more seriously. His demands also financially improved the lives of chess players…he allowed a lot of people to become professionals.”

The win against Spassky came at a heavy price for the American chess legend. Having made it his ultimate goal in life, Fischer found himself in a vacuum once he attained the title of World Champion in 1972. In 1975, he refused to defend his title against Russian grandmaster Anatoly Karpov after he could not reach an agreement with FIDE over the match conditions. He subsequently vanished from public view, kept alive in rumours and murmurs that he was spotted playing chess on the streets of Brooklyn, or if any news about his erratic, anti-Semitic statements came to light. He finally emerged out of seclusion in 1992, to win an unofficial rematch against Spassky in Yugoslavia, but this too, came at a heavy price since Yugoslavia was under a United Nations embargo at the time and his participation in the match violated an executive order imposing US sanctions on Yugoslavia, and resulted in the US issuing a warrant for his arrest. After this, Fischer lived the rest of his life as an outcast and an emigre. He was arrested in Japan in 2004 for using a passport that the US had revoked, but was eventually granted an Icelandic passport as well as citizenship. He died of kidney failure in Iceland in 2008.