- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

How Hasta Shilpa Heritage Village is helping traditional homes stand the test of time

When you step into Hasta Shilpa Heritage Village – an ethnographic open museum of traditional homes, shrines, and even entire streets depicting times gone by, you can’t help but be amazed. These are not structures that have been constructed to be representative of an era, community or culture. Rather, each of the 16 homes — nine are also being used as thematic museums —, 9 shrines...

When you step into Hasta Shilpa Heritage Village – an ethnographic open museum of traditional homes, shrines, and even entire streets depicting times gone by, you can’t help but be amazed.

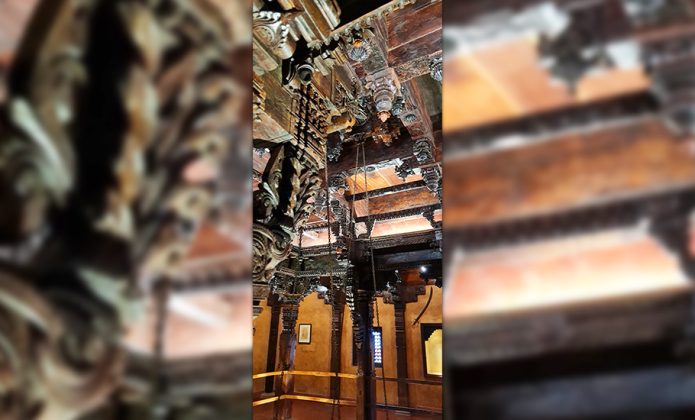

These are not structures that have been constructed to be representative of an era, community or culture. Rather, each of the 16 homes — nine are also being used as thematic museums —, 9 shrines and entire street side exhibits have been transplanted from various locations across Karnataka. Among the oldest structures is the Harihara temple from 1216 AD; the Kamal Mahal of Kukanoor, a royal residence, dating back to 1341 AD and a Bunt home from 1605 AD. The rest span across centuries with the most recent, Deccani Nawab Mahal, being as old as 1912. Artwork collections exhibited are from across the country and include textiles from Tamil Nadu, Kutch embroidery, tribal art from Bastar and more.

Each home you see here has been lived in, often by successive generations. But these homes have all ultimately shared the same fate – having to make way for modernisation. Rather than have these structures, with their architectural uniqueness and ancient construction methods lost to posterity, bringing them to Hasta Shilpa has given them a new lease of life, despite ironically, it being their final resting place. “And it all began because of the pain suffered by Vijayanath Shenoy, the founder secretary and author of the Hasta Shilpa Trust,” says Harish Pai, joint secretary of Hasta Shilpa Trust and part of restoration team for the heritage village since its inception.

Exploring and documenting

In the late 60s, Shenoy, who was born and brought up in Udupi began to work for the Syndicate Bank in Manipal. He was allotted an RCC home, which did not provide any cooling insulation during the harsh and humid summers of the region. Reminiscing his childhood home, with its false wooden ceiling and tiled roof, all designed to cool spaces naturally, he began to explore the villages around Manipal.

“Unlike today, there was no network of roads and transport facilities and so most of these explorations were on foot. Shenoy would tuck a paan into his mouth and walk everywhere looking for traditional homes, once finding the 600-year-old residence of the head man of Hirebettu village, around 10 kilometres from Manipal. He would meticulously document structures, construction styles and the people who lived in them. This way, in a decade, he covered most of South and North Canara and the Malnad region,” explains Pai.

In 1972, national guidelines with ceiling limits on land holdings were issued as part of the Land Reforms Act. This led to several landed gentry losing large portions of their land, giving impetus to joint families going nuclear and migrating to cities and towns for work.

“Maintaining large homes became difficult and the desire for modernity began to creep in. Pillars from dilapidated homes were broken down to make planks for dining tables with little regard to their value and this pained Shenoy. Wanting to rescue what he termed iconic cultural symbols of our past, Shenoy began to retrieve, pillars, windows and door frames, ending up with a large collection of them. He used this collection, amassed from 60 different houses, he used to build his own home in 1986, naming it Hasta Shilpa,” explains Pai.

The home became a conversation starter and based on advice from the local administration, Shenoy registered the Hasta Shilpa Trust, a not-for-profit-public-charitable trust in 1991 and applied for land to transplant homes that were on the way to being demolished. He was sanctioned six acres of land in December 1988 and in mid-1999 the trust received funding from the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD) to kick-start the project. And the first of many traditional homes began to be transplanted.

Transplanting history

Thanks to Shenoy’s extensive recce, he knew of homes in the region that were coming down or were abandoned. He began to bring in structures of various typologies. There is the Mudhol Palace Durbar Hall (1816) built by the Maratha Ghorpadas ruling Bagalkot. The architecture with Rajasthani influences was locally crafted in teakwood. There is a Peshwa Wada façade from Belgaum of a single-storey structure with a Jharoka, the only surviving part of the Wada. The intricate wood carving of Kamal Mahal is unique because they are assembled without any fasteners between the wooden components, giving them a seamless look. There is also the Mangalurean Christian home with its Roman Gothic architecture and with a rarely seen terracotta columned verandah.

The Bhatkal Navayath Muslim House (1805) showcases a main door with Arabic calligraphy, a range of crockery and typical artefacts of the Navayath culture. These are just some of the structures to be seen.

To be added to this collection is Shivabagh, the stately, royal-looking home of Subbanna Shivarao that was built in the 1890s on a hillock in Shivabagh in Mangaluru. “Back then, there were no hotels and prominent families hosted visiting dignitaries to the district. The home has hosted Jawaharlal Nehru and Rabindranath Tagore among others,” says Pai adding that when the team got wind of the home being dismantled, they contacted the family, who donated the structure to the museum. It has now been dismantled and brought to Hasta Shilpa.

While Shivabagh will take some time to come up, it is interesting to see how these homes are transplanted. “Once we fix on a home, we take detailed measurements of every element of the plan, elevation and sections. Drawings are made of every element. Every aspect is coded and placed on a plan. This is important because everything is handmade and has no standardisation. Unless properly numbered, re-assembly will be difficult,” explains Pai.

Once all the woodwork is dismantled, it is carefully transported to Hasta Shilpa and placed in dedicated work sheds. Dismantling usually takes place between January and April. During the monsoons, the carpenters work on restoration, fixing any deformities in the wood. The (plinth) foundation work begins in April and May. In August, the walls start to come up and by November, assembly of the wooden structures begins. Where there is a first floor, the work of raising walls and placing the roof has to happen in the months preceding the rains. The plastering work happens during the rains. It is a two-year cycle from dismantling a home to reassembly.

“It is sad that a lot of the mud-building technology has been lost with time. We did find a traditional mud mason and learnt that he used to soak a creeper in water to extract a gelatinous substance that was great for binding mud. Unfortunately, he couldn’t remember the name of the creeper. Moreover, we have found that a 150-year mud house is more susceptible to damage than a 300-year house, showing how the knowledge was already diluted along the way,” says Pai, adding that they do continue to use ancient mud plastering techniques. In certain external areas stabilised mud mortar is used and for internal walls, mud and lime plaster with sugarcane molasses is used.

Today, besides the homes and shrines, there are several smaller museums of artefacts, crockery, cutlery, and entire streets with shops like a soda-making shop, tailor, barber, medicinal store and more. You can choose to take a guided tour or use a detailed book available for purchase (Rs 500) or the digital pdf you can download from the official website for a self-guided tour. The structures are numbered and it is the ideal sequence to follow when you explore. Entry charges that go towards maintenance of the museum and are currently Rs 300 for adults; Rs 150 for senior citizens and college students with valid ids. School students are charged Rs 60 (private) and Rs 30 (government) schools.