- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

How a partially blind artist sees the world: ‘There is art in everything’

Six months ago, artist Natesh Muthuswamy lost 70 per cent of his vision due to diabetic retinopathy. A peripheral neuropathy followed. Now, restricted to a chair with a spectacle fitted with high-powered magnifying lenses, Natesh says he will continue drawing with his blurred vision. “I have lost my focus. But I can manage with what is left. I draw a lot of baby elephants now,” says...

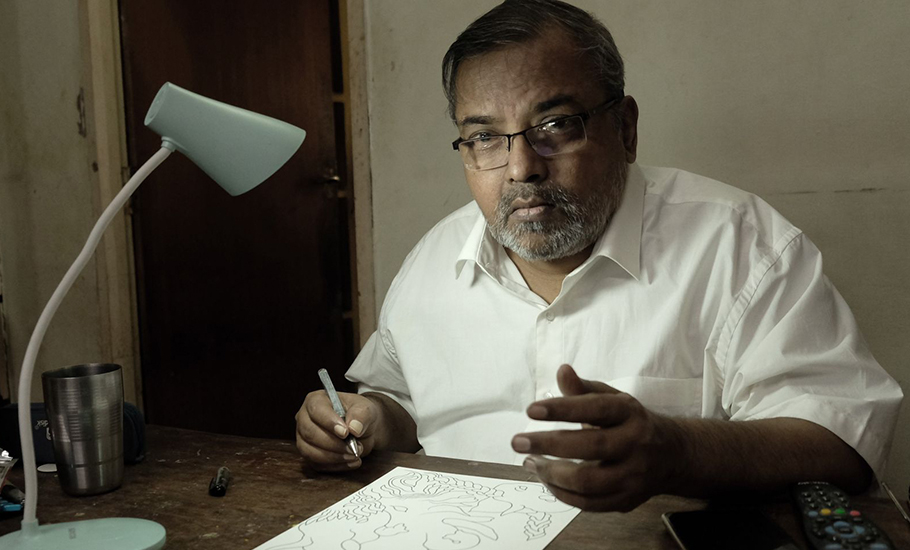

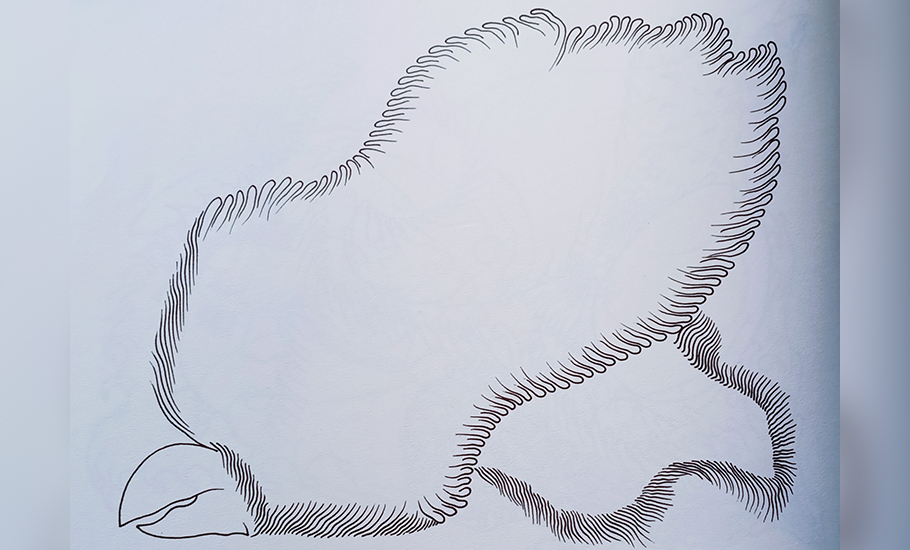

Six months ago, artist Natesh Muthuswamy lost 70 per cent of his vision due to diabetic retinopathy. A peripheral neuropathy followed. Now, restricted to a chair with a spectacle fitted with high-powered magnifying lenses, Natesh says he will continue drawing with his blurred vision. “I have lost my focus. But I can manage with what is left. I draw a lot of baby elephants now,” says the 62-year-old.

A couple of weeks ago, he published his book, Before Becoming Blind, a collection of 82 sketches by him. “I published my book because somewhere I am conditioned to think that art is a book,” he says. “I saw many art books as a student at the library of the Madras School of Arts [now known as the Government College of Fine Arts, Chennai]. I always thought art was in the form of a book, a reason why I brought out a compilation of my works in the form of a book.”

As a child, Natesh started drawing on papers that his mother brought home from her work. Even though his penchant for drawing got strengthened in the coming years, Natesh miserably failed in science and mathematics while pursuing his Bsc (physics) at the Loyola College, Chennai. It was during this time Natesh’s father Na Muthuswamy founded the famous contemporary Tamil theatre group Koothu-P-Pattarai (in 1977). With writers, artists and activists as visitors, his house in Chennai became a melting pot of ideas.

Natesh grew up witnessing the political and social developments in Tamil Nadu as well as in the country. However, Muthuswamy was worried about his son’s failure in academics. So, he asked Natesh to join the Government College of Arts and Crafts, to pursue art, his favourite subject.

It was a turning point in Natesh’s life during the six years (1980-1986) that he spent as a student at the Government College of Arts and Crafts in Chennai. He found great artist-teachers like RB Bhaskaran, G Chandrasekaran (popularly known as Chandru) and KM Adimoolam under whom he picked up the essentials of drawing.

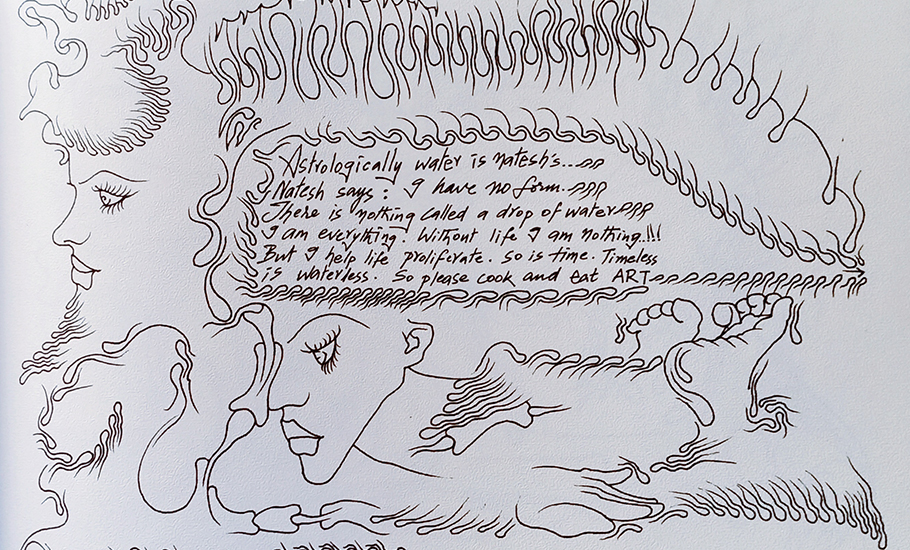

Natesh’s drawings represent an era of cultural consciousness of Tamil Nadu. The figures of human beings, birds and animals acquire an element of theatre and folk in his drawings.

Even though Natesh started drawing when he was barely five years old, it was his association with Koothu-P-Pattarai that shaped his thoughts. “In 1969, my father Na Muthuswamy produced Kaalam Kaalamaaga (Time after Time), which is considered the first modern play in the history of Tamil theatre. He wanted to create a new idiom for the contemporary stage based on movement and sound as the main mode of storytelling. Many writers and artists would visit my father quite often. I grew up listening to what they spoke. It gave me insights into various cultural and social issues of that time,” he says.

Natesh says he was an actor before an artist and the credit goes to veteran theatre director and actor KS Rajendran who passed away recently. “My father invited KS Rajendran to Koothu-P-Pattarai in 1984 when he finished his course at the National School of Drama. It was Rajendran who first made me act in a play called Suvarottigal directed by him. So, I was an actor before I became a full-fledged painter,” says Natesh.

“When I was doing my final year at the Government College of Arts and Crafts, I also performed a major role in one of the plays directed by Rajendran. I still remember that performance which took place in Kerala’s Ernakulam in 1985,” says Natesh.

At Koothu-P-Pattarai, Natesh was also designing and lighting sets, training actors and writing plays. He would travel with his playwright father Muthuswamy to the villages of Tamil Nadu. “My father was doing many experiments in the field of theatre, using the existing classical and folk forms that were still being practised among the communities in villages. Those innumerable trips with him helped me learn more about theatre and art, particularly about the chemistry behind figures and movements,” he says.

At the same time, he was getting involved with political and social issues. The Bhopal Gas Tragedy in 1984 was one of them. “We, a group of youngsters in Chennai, created more than 350 posters, questioning the tragic incident. I did more than 150 posters myself. The event evoked tremendous response,” he says.

Caught between theatre and art, Natesh felt a little confused when he passed out from the Government College of Arts and Crafts in 1986. Finally, he chose to be a painter.

So, what brought Natesh to stick on the world of art despite being successful in various fields of theatre production?

“I have been drawing since I was five years old. Unlike painting, drawing is easy. Any piece of information, whether it is a normal telephonic conversation, could be a subject of my drawing. My drawings are strong impressions of a particular moment. I mean, emotions and expressions that take place in that moment,” says Natesh.

There is art in everything, he adds. “See, the mobile phone that you use or the shirt that we wear. There is art in everything around us. Art is not just the job of a single person. I am just making the elements reflect on a paper using my own scripts.”

Natesh has exhibited his works in various cities in India as well as abroad. But he still has more than 4,000 unexhibited works in his collection. Until 2008, he had been exhibiting all his works but lost interest later.

There is a reason for it. “Good art galleries are essential. They will talk about your work and give an idea about your work to those who are interested in art. Unfortunately, in India, art galleries function as commission agents,” says Natesh, who is managing trustee of Koothu-P-Pattarai.

Natesh knows that his movements are restricted due to his medical conditions. “It was after my father’s death in 2018 that I have been facing serious health issues. He was a great source of energy. I now focus on drawing, which I have been doing since I was five years old. It is easy unlike painting, which is time-consuming. I can finish one in five minutes, but there must be an element of passion and urge behind each creation,” he says.

After becoming partially blind, Natesh doesn’t feel that it’s the end of the road. “My personality is lost. When you can’t move or see, you lose your personality. But my mind is active. If you speak to me over the phone, you feel as if I am a normal person. Only if you meet me, you will see the difficulties that I have been facing. Despite all difficulties, I will keep on drawing. It’s another way of redefining myself as an artist,” says Natesh, who believes that his sketches are self-reflective.

One can see anthropomorphic representations of women in his drawings. “Many are known to me. They represent a form of feminine ecology. I was also fond of Phantom comics. Images of elephants, rhinos, birds, tigers and horses in my drawings take shape from those comic narrations,” says Natesh, whose love for nature and its regenerative power adds strength to his lines.

Intriguingly, Natesh doesn’t sign his sketches saying that the viewers are the owners of those works. “I have allowed drawing to lead my life. I have lived my life as a draughtsman. I will have a particular fantasy and that would carry me for some time only to be replaced by another fantasy. There is no sense of belonging in creative making. Once the process is over in creative making, there is no ownership. You don’t own the work anymore,” says Natesh in the foreword to his Before Becoming Blind, published by Kadavu Publications, Palani.