- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Hiding behind high walls, shocking reality of India's caste system

Early on November 29, seven-year-old Akshaya slid her hand into her mother’s and walked as fast as her little legs could carry her. Akshaya was worried she would be late for school that’s barely 100 metres away from her home at Nadur village in Tamil Nadu’s Coimbatore district. Akshaya was considered one of the smartest kids in her class, and this wasn’t something she took lightly. It...

Early on November 29, seven-year-old Akshaya slid her hand into her mother’s and walked as fast as her little legs could carry her. Akshaya was worried she would be late for school that’s barely 100 metres away from her home at Nadur village in Tamil Nadu’s Coimbatore district.

Akshaya was considered one of the smartest kids in her class, and this wasn’t something she took lightly. It was her Tamil handwriting — neat and clean lines — on the blackboard that made her a favourite among her teachers.

But little did her teachers know that it would be Akshaya’s last day in school. The seven-year-old and her mother Nathiya were among the 17 people crushed to death by a 20-foot-tall, 80-foot-long and 2-foot-wide stone wall that fell down on their houses around 4.40 am on December 2 following incessant rains.

The formidable wall — now being called the ‘untouchability wall’ by news media — was reportedly constructed by a businessman, Sivasubramanian, a caste Hindu, on his two-acre property to isolate the Dalit settlement of Arunthathiyar community in Arunthathiyar (AT) Colony.

“A loud thud woke us up. We came out of our houses only to see a pile of debris — the wall had fallen on the tile-roofed houses, crushing everyone and everything underneath. We did not even hear people screaming for help as everyone was sleeping. The wall was as tall as the coconut trees in their house,” says P Kanmani, a nearby resident.

Also read | Mettupalayam wall collapse: Activists allege caste angle

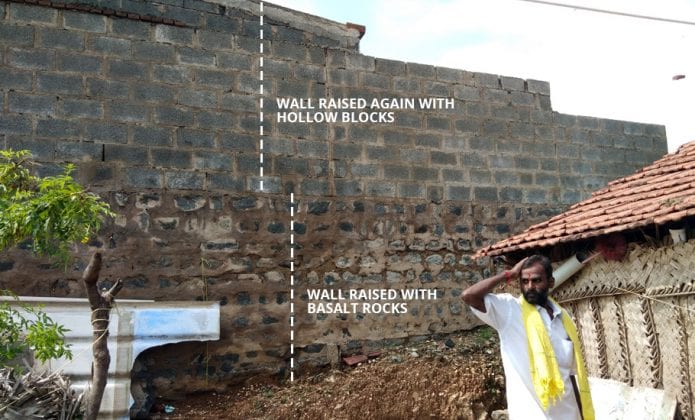

Another resident, K Pavithra, who has been residing in the locality for over 40 years, claims that earlier when AT Colony people approached Sivasubramaniam to reduce the height of the wall — that was raised from 6 feet to 20 feet — he let his dogs loose on them.

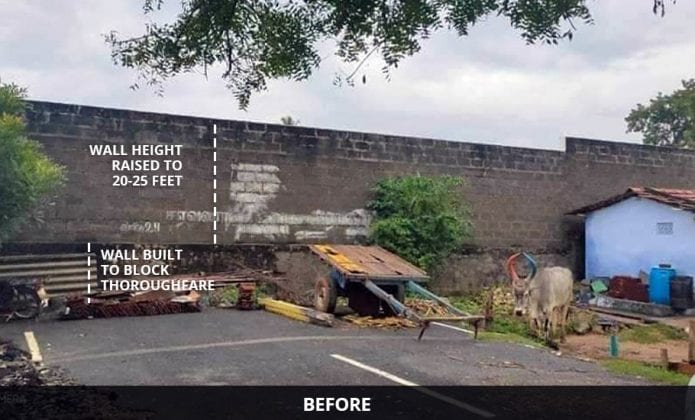

As many as 300 Arunthathiyar community people in AT Colony were given patta (land deed) at Nadur village in Mettupalayam taluk back in 1992. However, soon after caste Hindus started to settle in nearby lands, a number of ‘untouchability walls’ started to crop up behind their houses — as high as 15–25-foot-tall. “After one owner raised the height of his wall, other caste Hindus followed suit,” Pavithra adds.

The Federal found five such walls built by caste Hindus to separate their houses from those of the Arunthathiyar community people.

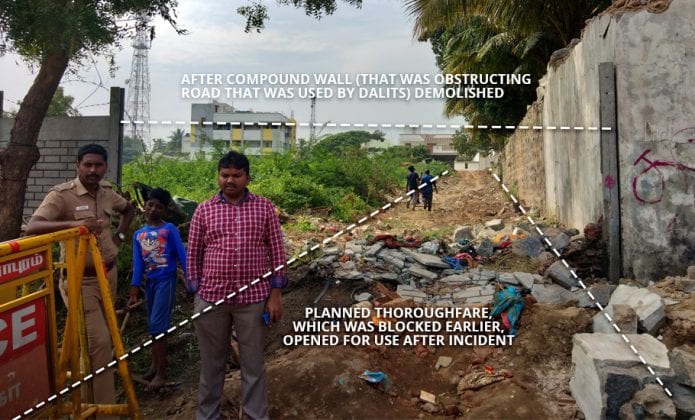

“The caste Hindus have also blocked as many as three scheme roads (thoroughfares earmarked for development under various schemes) that were supposed to connect our village with Mettupalayam-Ooty main road and constructed walls to obstruct us from taking that route,” says 40-year-old D Santhi, who resides by the side of a scheme road.

Although the accused parties, Santhi adds, claim to have built the compound walls to protect their property, she and other AT Colony residents feel otherwise. “What is the need for them to construct such huge walls only on one side — the side facing AT Colony — while on the other three sides of their houses, the wall height is less than seven feet,” asks Santhi.

While one such ‘untouchability wall’ on the scheme road was removed after the wall collapse killed the 17 people, AT Colony residents allege that caste Hindus have encroached land meant for scheme roads and built their bungalows on it.

According to residents, while most of the Dalit men work in farms in and around Mettupalayam, the women work in bungalows in the locality as maids and describe their job as “bungalow work”.

“Initially, even we thought they were just compound walls. It was only after we asked them about the imposing height [of the walls], that they told us to our face that they did not want to see Dalit faces first thing in the morning,” says P Sharanya, who works in one of the bungalows in the locality.

Sharanya is unable to fathom what would go wrong if the “bungalow people” see “Dalit faces in the morning as soon as they wake up”.

A woman in her mid-30s, whose father too had built a similar wall, says she did not know it was a “wall of untouchability”.

“We were told that there is a scheme road marked on our plot. So, we built our building in an area that was not earmarked for it. But as there were no development work carried out, my father told me that he had raised the wall.”

She, however, believes the tile-roofed houses of the Arunthathiyars were an eyesore for their beautiful bungalows with lush green lawns. “But it [the wall] was not intended on caste lines,” she claims.

However, the caste divide in the village clearly runs deeper.

According to the Dalit residents, it took over 30 years for them to gain entry into the village temple. “It wasn’t long ago. I remember it was only when my daughter reached high school, we were allowed inside the common Mariamman temple in the village. Until then, we were called only to play the Jamab — a traditional percussion instrument — during the temple festival, that too from outside the temple. Don’t know how many more years it will take for them to treat us as equals,” says P Vennila, whose daughter is a BCom first-year student now.

UK Palanisamy, who belongs to the Arunthathiyar community and is a cadre of the Communist Party of India (CPI), has been fighting for the removal of the ‘caste walls’ since 1998.

“But we did not take it up as a big movement as the people here wanted a peaceful environment. Our children have started going to the schools and colleges only recently. So, we did not want to spoil that environment,” he says.

Also read | Dalits vs Dalits: How caste walls are getting new narratives

But Palanisamy has not stopped questioning the “caste walls”.

“Of all the walls, the one that crumbled and crushed 17 people to death was the tallest and it is the only wall that is built with basalt rocks. Whenever we questioned, they would abuse us, hurl casteist slurs and chase us away, saying nothing would happen,” he adds.

Talking about the administrative side of the problem, a retired surveyor of Mettupalayam municipality tells The Federal that the proposed scheme road should have materialised a decade ago.

“However, whenever the matter of constructing a road on scheme roads crops up, elected members of the local body — who are mostly caste Hindus — would object to it and put the matter on the backburner. So, it never materialised,” he claims.

Even when any civic work is proposed for the Arunthathiyar Colony, the elected representatives hardly pay heed,” the retired surveyor adds.

P Kanmani, another resident, says, “Even these roads [within their locality] were laid only when the chief minister [Edapaddi Palaniswami] visited the spot to condole the wall collapse deaths,” she says, pointing at the freshly carpeted tar roads.

Frustrated over the apathy, she asks if AT Colony has to lose someone every time their village needs basic amenities.

Mettupalayam MLA and AIADMK leader OK Chinnaraj claims he was unaware that such a discriminatory wall existed or the fact that bungalows and such compound walls are blocking scheme roads in the village.

“They might have told the local body officials, but I was not aware about the developments. Had I been informed, I would have taken action. We will soon remove the walls and houses obstructing the roads and discriminating the AT Colony residents,” he says.

Municipality Commissioner Suresh Kumar too sounds ‘hopeful’ and claims work will begin soon on a scheme road from AT Colony connecting the roads leading to the Mettupalayam Road.

He was, however, “unaware” of the other scheme roads and the high walls blocking them, as he had joined just 15 days ago.

According to Untouchability Eradication Front’s state general secretary K Samuel, Dalits have been facing this form of the discrimination for years now.

“Although they claim it [raising the height of the walls] was unintentional, these people feel entitled to carry out such illegal activities. Will any Dalit be able to construct such huge walls and claim it was not discriminatory after killing 17 people?” he asks.

“If it wasn’t intentional, they would have removed the walls in the first place when people approached them to reduce the height,” Samuel adds.

But it’s not just the caste Hindus that Samuel and others from AT Colony are miffed with. Accusing the police and administration of caste bias, Samuel says, “This was evident during the recent lathi-charge on protesters following the wall collapse incident. Policemen too hurled casteist slurs at the Dalit villagers and beat them up for protesting against the caste Hindus.”

What has hurt the villagers most, they say, is how everyone — from police to politicians — have sided with the rich and the powerful. “This is enough to say how high the walls of casteism are, literally,” says Kanmani.

One wall, she adds, may have collapsed, but the caste divide has only deepened.