- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

Ground report: Paying the price for 'free-and-fair' polls at Pulwama

There’s a chill in the air as midnight descends on Kangan village in Pulwama district of South Kashmir on April 29. Two youngsters — 21-year-old Danish Ashraf Dar and his 14-year-old cousin, Shahnawaz Ashraf Dar — are fast asleep in their home. Fourteen others, including two children, are also curled up in the house. Anantnag: the economic hub of Valley echoes of militancy Anantnag,...

There’s a chill in the air as midnight descends on Kangan village in Pulwama district of South Kashmir on April 29. Two youngsters — 21-year-old Danish Ashraf Dar and his 14-year-old cousin, Shahnawaz Ashraf Dar — are fast asleep in their home. Fourteen others, including two children, are also curled up in the house.

- Anantnag: the economic hub of Valley echoes of militancy

- Anantnag, also known as Islamabad, is one of Jammu and Kashmir’s oldest districts. Located 1,600 m above sea level, Anantnag city is the third largest in the state with a population of over 10 lakh people.

- The city, 53 km from the state’s capital Srinagar, has a high concentration of troops as it lies on the strategic North-South Corridor road. Anantnag is of the four southern districts of the Valley where local militancy is gaining ground. After the recent Pulwama attack where 40 CRPF jawans were killed, the Lok Sabha election in this constituency is being held in three phases.

- The district houses the highest number of tourist destinations, making it the economic hub of Kashmir Valley. These destinations include the city square Lal Chowk, where Jawaharlal Nehru raised the Indian flag in 1948.

- Anantnag is famous for exporting handicrafts, handloom products, saffron, apples, apricots and walnuts. Due to its exporting capacity, the district, with a total GDP of $3.7 billion, was declared a major Towns of Export Excellence in 2010.

Around 2 am, about a dozen police and armed forces personnel enter the narrow pathway that leads to the house and cordon off the building. One of the policemen repeatedly bangs on the door, startling the family awake but they are too terrified to react. Soon, the police force the door open, and three of them enter with guns in hand. The police inform them that it is a cordon and search operation (CASO) conducted by security personnel to control insurgency in the Valley. They ask all the women to get inside one room while they look for Danish and Shahnawaz.

The two youngsters take a beating from the security forces as anxious family members watch on. They are eventually taken into custody so that they can reveal the identity of their friends in the neighbourhood who pelted stones at the armed forces earlier. The family assumes Danish and Shahnawaz will return soon.

It is 6 am, four hours since their arrest, and they still hadn’t returned. The second leg of the three-phase polling in Anantnag constituency has begun. Shahnawaz’s mother and uncle visit the Pulwama police station, about 5 km away from their house, to meet them, but the police won’t let them in. The officials inform the family that they identified Danish and Shahnawaz as stone pelters and they took them in to ensure a “free and fair elections” ahead of phase five on May 6, when Pulwama will exercise its franchise. No assurances are made on when the two youngsters will be released.

Similar cries elsewhere

On the same night, the police arrested youngsters Umar Ahmad Dar and Mudasir Ahmad Wani from their homes in the same village. While their families await their return, the police told The Federal that they would not be released until the elections are over.

Shahnawaz’s mother, Famida Banu, cries as she says her son had a mandatory test to take in the matriculation board examination at school the next morning. “I visited the police station four times this week but met him only once. They beat him in front of us. They show no mercy, we are helpless,” she says.

When asked if they were aware of their kids pelting stones, the answer was a definite ‘no.’ Danish and Shahnawaz’s uncle, Abdul Amir Dar, narrates an incident where, while playing cricket a month ago, one of the kids got injured in the head, and Danish — a first-year degree college student — put him on his shoulder and ran for help. He says the police may have mistaken this as a stone pelting accident and noted his mobile number and identity.

About a kilometre away, in Murran village, people narrate similar stories of arrests at midnight. Most of them are youngsters. The police book them under the Public Safety Act, a preventive detention law where the accused may be confined in prison for an indefinite period without trial.

After the Pulwama-based suicide bomber Adil Ahmad Dar attacked and killed a convoy of 44 Central Reserve Police Force soldiers, the CASO and midnight arrests intensified in and around Pulwama. Villages like Gudoora, Newa, Parigam and Kakapora, which are around the police headquarters, also became targets.

Though officials did not confirm the number of civilian arrests during the CASO, villagers say the police picked up at least 18-20 youth from each village.

Police show no mercy on kids

Around 3 am on the same night, the police detained 12-year-old Shahid Riyaz Thoker from Murran. His crime? Aiding stone pelters in the region, the police say. Shahid, a juvenile, was sent to juvenile observatory home in Srinagar about 35 km away. His father, Riyaz Ahmad, a daily wage worker, was forced to make daily visits from Pulwama to Srinagar to meet his son. He lost his earnings for the week in the process.

“What choice have I got if not leave my job and go meet my son? How can I let this young boy stay away from us,” asked Ahmad over the phone while waiting to meet Shahid. Another family member, Nissar Ahmad Yatoo, too, was picked up by the police the same night.

In another locality, the police broke open the door of a house to arrest a youth while they jumped walls and cordoned the house in another, a detained person’s family says.

“They pulled me out first as they did not find my brother, who was sleeping in another room. They beat me and verbally abused my sister for stopping them,” said Muzaffar Ahmad, who owns a butcher shop in Murran. “They let me go as soon as they found my brother (Imtiaz Ahmad Ganai), who they claimed was a stone pelter.” The police took Ganai into custody the same night.

When Muzaffar and his sister visited the police station and asked the officials to show them the video based on which they identified their brother as a stone pelter, he claims the police showed them a video that did not have his brother.

“I can understand when it’s the Army as they have been doing this (search and arrests) for years. But the state police was ours. How could they do this to us? If the election is on May 6, why arrest people a week before?” asks Muzaffar.

About 200 metres away, a youth who owns a car went to rescue it during one of the stone pelting incidents in Murran last week. The police surveillance vehicle caught him on camera and they arrested him by barging into his house at midnight, claiming he was a stone pelter too.

Police action and its reflection on the electoral process

With no government in place in Jammu and Kashmir after the Peoples Democratic Party- Bharatiya Janata Party’s alliance fell apart in July, the state came under president’s rule. And the Centre is seen as a force behind these military actions.

The anger against the armed forces and local police will reflect in the electoral participation. Of the 30-40 people The Federal spoke to across various villages in Pulwama, not one said they would go and vote on election day.

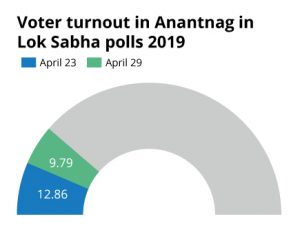

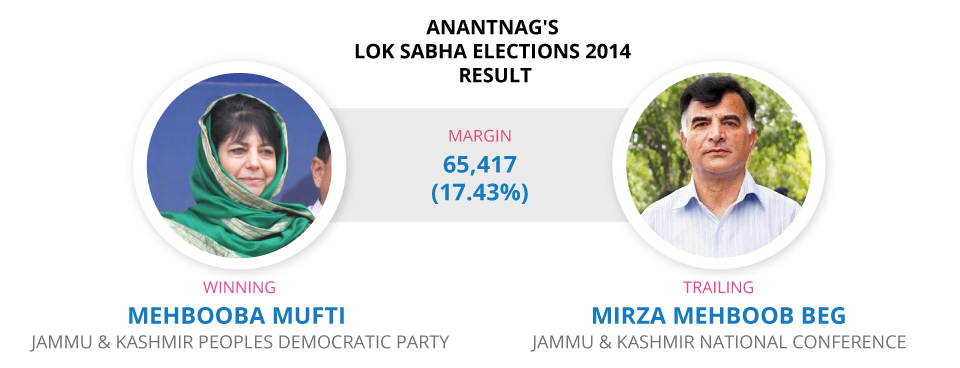

Pulwama and Shopian are said to be crucial for former Kashmir chief minister Mehbooba Mufti of PDP. While the first phase saw 13.61 per cent voting, the percentage dropped to 10.3 in the second phase on April 29. People expect a single-digit turnout on May 6 because of the arrests and search operations.

While the police say that they work to ensure the election process goes smoothly, their actions terrorise the villagers who feel threatened to come out on the streets to vote. In Pulwama, neither the local issues nor Article 370 of the Indian Constitution that grants special status to Jammu and Kashmir, which the right wing parties seek to abolish, were the point of contention for the election. Simply put, it was the nocturnal raids, midnight arrests and the CASO that worried people.

Police say their actions are right

As this reporter entered the Pulwama police station to meet some of the arrested youth, the police denied permission. When questioned whether Shahnawaz was allowed to take his exams or not, the police said nothing except that he was in jail.

High-rise walls and two big gates protect the Superintendent of Police’s office located about half a kilometre away from the Pulwama market. People walked in and out with requests to meet their dear ones. One woman cries to the police but the officer on duty said it was just another ‘routine’ during the election and not to worry. In 200 metres, there are three police checkpoints to meet the SP. Only some get permission to meet him.

A senior police officer, sitting outside the lawn area with other police officers in the SP office, first denied that they detained any under-18 teenagers. But when The Federal narrated some incidents, the officer, on condition of anonymity, said they do not go by the age of the person, but they go by the police surveillance footage of stone pelting incidents and pick up people accordingly.

“We don’t have their names. We go by photos and identify people with the help of our intelligence team. We do this to ensure a free and fair election,” the officer said. “I will be held responsible if anything happens to my staff (armed forces and police). So, I have to take preventive action. We only arrest those who pelted stones at the police and armed forces before and are repeat offenders.” The officer says they do the operations at night because, a couple of times, the villagers threw burning charcoal when they tried to arrest people during the day.

When asked if the victims, teenagers under 18, will be allowed to go to school or take exams/test, the officer gets angry by the term ‘victim.’ He questions the reporter’s integrity and goes on to show a couple of stone pelting videos on his phone. In the video, the locals attack police and the armed forces vehicles. “I show them no mercy. What are they fighting for? Did we hurt women? Did we loot them? Did we stop them from performing namaz (prayers)? What is the freedom they are seeking?” the officer asks.

However, villages echo a different sentiment. Nawaz (who wishes to go by his first name) says, “If there are terrorists in a particular locality, it’s between the police, armed forces and the terrorists. They should not victimise the entire village. But since the police do not follow that principle, youngsters, angered by the police action, pick up guns and stones. And our votes will not change anything when it hasn’t in the past two decades.”