- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

Gigantic, ferocious, mischievous… the asuras of religion we cannot do without

Each religion, be it Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Islam and Christianity, has its own demons. Mara is the personification of the evil and tempter of man in Buddhist mythology and Hariti is the mother of demons. The Tirthankaras of Jainism tried to reform the demons, destroying their evil propensities. The Hindu epics and puranas have produced innumerable demons. While the gods get prominence...

Each religion, be it Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Islam and Christianity, has its own demons. Mara is the personification of the evil and tempter of man in Buddhist mythology and Hariti is the mother of demons. The Tirthankaras of Jainism tried to reform the demons, destroying their evil propensities. The Hindu epics and puranas have produced innumerable demons.

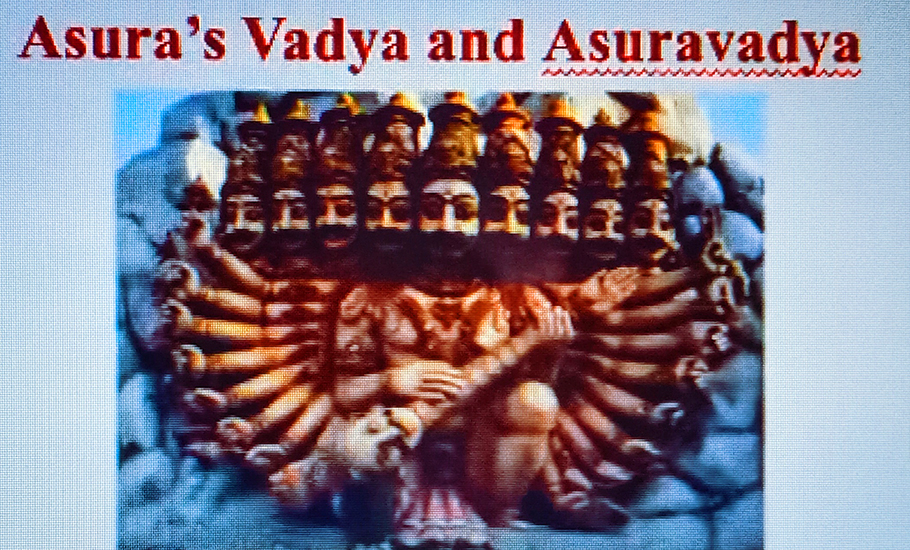

While the gods get prominence in the epics and puranas, the demons are considered inauspicious. Indian mythologies and literatures characterise asuras as oversized or dwarfish, one-eyed, pot-bellied, with protruding teeth, disfigured face, hump-backed, multi-headed or with no head at all. Despite having these awful descriptions attributed to them, there are some who are known as maestros in musical instruments. Ravana, Banasura and Surapadma are asuras who are known to have great skills in playing musical instruments.

“Ravana was an expert in playing ‘veena’, Banasura in ‘mizhavu’ and Surapadma in ‘timila’ (an elongated hour-glass shaped percussion instrument),” according to Akhil KN, a research scholar at Department of Archaeology, University of Kerala.

Demonology is the study of demons who are regarded as harmful, heinous or malicious causing uneasy conflicts and undesirable diseases, and it is also the study of a set of beliefs related to demons. In a recently held international webinar, conducted by the Department of Archaeology, University of Kerala, 26 scholars and experts from different parts of the world spoke on “Demonology in South and Southeast Asian Sculptural Art”.

Interestingly, Ravana, Banasura and Surapadma are devotees of Shiva, the god of dance and music. “Ravana is the asura frequently shown as playing either a bowed veena (Ravanahatta) or a normal veena. Ravanahatta sculptures are scanty. It is noted in some Ravana sculptures of Sri Lanka. It is believed that Hanuman picked up this instrument and brought it to today’s north India after the end of the Ram-Ravana war. Ravanahatta is today played in some parts of Rajasthan and Gujarat,” said Akhil, while speaking on ‘Asura’s Vadya and Asuravadya in Sculptural Art’ at the webinar.

“According to ‘Bhagavathapurana’, Banasura is an expert in percussion instruments. But in the Mysore school of painting, he is shown as playing stringed instruments apart from percussion instruments. In Kerala, however, Banasura is shown as playing a regional percussion instrument called ‘mizhavu’. Though referred to as a musician in literature, Surapadma playing his musical instrument ‘thimila’ is not seen in sculptures so far,” he added. Many don’t know the other side of Ravana, who was an ardent devotee of lord Shiva. “Ravana is highlighted as a villain in the Ramayana. But there is another side to his personality, which many don’t know. He was a scholar, musician and a good ruler. We have a lot of sculptures of Ravana that display his positive side,” said Sivasankar Babu, a heritage enthusiast, while speaking on ‘Ravan – The Brahmana Among the Demons’.

‘Balagraha’ is a combination of two words ‘Bala’ and ‘Graha’. ‘Bala’ is pertaining to children while ‘Graha’ means to seize or grasp. ‘Balagrahas’ are mentioned in a list of afflictions, any of the demons that are believed to harm children,” according to Chaitanya Arun Sathe, an independent researcher from Poona. He said the Graha-Rogas have separate entities from other general disorders and they affect many paediatric age groups. Both mythology and medicine describe Balagrahas, as demonic beings, and their attraction to blood; an embryo-eating menace (Atharva Veda), a deity dedicated to afflicting pregnancy, causing stillborn births; another assigned to destroy a child during the first 16 days after birth and then disease-causing snatchers do their work.

Chaitanya said the first reference of Balagraha is seen in Rig-Veda as Bhutas’ menacing foetuses and neonates. The ‘Vana Parva’ of Mahabharata explained the morphology of the Grahas along with their attack on up to 16-year-old children. Markandeya Purana talks about 16 demons out of which eight are male and the rest are female. Shatapatha Brahmana depicts Graha as some mythical power. Grahas and Atigrahas each eight in number are described in Brihadaranyaka Upanishad.

“Acharya Sayana described the word Grahi to be harming the child. The Sushruta Samhita, Charaka Samhita, Kashika Sutra, Kasyapa-Samhita and Skanda Bhaishajya also mentioned Graha Rogas, Grahas attacking in foetal life, infancy, and paediatric age group are explained,” said Chaitanya, while speaking on ‘Balagrahas: Sculptures of Demonic Spirits Responsible for Infant Mortality’.

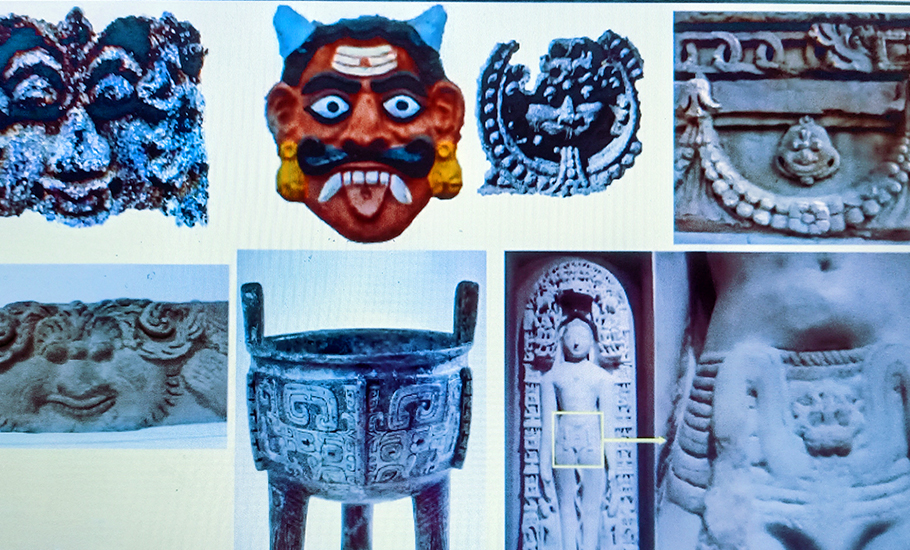

Were they worshipped? Chaitanya said worship of these Balagrahas was popular in the pre-Kushan and Kushan era of 1st-3rd century CE. “Several sculptures and panels of Gandhara, Kuṣhaṇ period were found depicting these Balagrahas,” he added.

In the night during which Sakyamuni meditated with the aim of reaching awakening, he was attacked by Mara and his army of demons. The legend is well-known in art where it appears from an early period and was constantly reproduced through centuries. “A profound change took place in Bihar and Bengal from the 10th century onwards in the composition of the army with the presence of Hindu deities showing their aggression towards the Buddha and finally submitting to his power, thus showing a radical transformation in their personality. It is in this context that they are then introduced into the iconography of various terrifying Buddhist deities to whom they submit,” said Claudine Bautze-Picron, a Buddhist scholar of the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Paris.

Within the expanding pantheon of Buddhism, there were multiple cases of conversions, assimilations and inclusions of a plethora of folk deities and also demons within the folds of Buddhism. “One such case is that of Hariti, who was inculcated into the Buddhist pantheon, through the positive teachings of Lord Buddha,” said Pallabi Bagchi of the Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, the Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, Vadodara.

“The transition in her identity from that of a child devouring demoness to that of the Goddess of fertility, the mother of demons and protector of children, highlights the role of Buddhist teachings and knowledge to lead the people into the right direction. This transition from a negative to a positive character is sculpturally depicted, especially in the Gandharan and Mathura schools of art. While her journey within the Buddhist narrative ends with her conversion, her story continued to spread, through art and stories into Southeast Asia,” said Bagchi, during her lecture on ‘Demoness Hariti: Mythology, Art and Dissemination in South and Southeast Asia’.

Hariti gained popularity as time passed. The Hariti cult seems to have been well-established by the Indo-Greek and Kushan times as it is indicated by the archaeology and sculptures of this period, according to Vinay Kumar, another scholar. “Hariti with her clan was also part of the progressively significant devotional cult. Hariti flourished as a child protector. She was an ogress-turned-goddess. She was one of the most represented sculptures in Buddhist art of Gandhara. She was a Yakshini at first with her consort Panchika, who was later turned into a goddess, as mentioned in Hariti Sutra, a Hinayana text. Now, during the advent of the smallpox pandemic, she was established as a goddess who protects children from smallpox in the Mahayana period during the Kushanas,” said Vinay Kumar, of the Department of Ancient Indian History, Culture and Archaeology, Banaras Hindu University.

Symbols have been acting as bridges between man and his ideas. One of the commonly found adornments in Indian art is in the form of Kirtimukha, a demon-like ferocious face. Kirtimukha resembles a demon face depicted in both lion and human form having building eyes, wide open nostrils, stout horn, curled eyebrows and frowns on forehead. “The general concept behind the demon-like motif is to warn against gluttony and ward off evil eyes. Kirtimukha generally represents animal features such as lion, ram, dragon and serpent which vary individually or in combination of both,” said Nayancy Priya of Department of Ancient History Culture & Archaeology, Nava Nalanda Mahavihara, Nalanda, Bihar while speaking on “Kirtimukha : A Demon Like Ferocious Face.”

Kirtimukha is not always ferocious though. Nayancy said Kirtimukha is depicted with a laughing and calm face as well. Earlier, the Kirtimukha was exclusively used at Shiva temples but later on it began to be used indiscriminately on various shrines to ward off evil. “The authority of the motif goes back to its Chinese counterpart which is depicted on the bronzes from the Shang dynasty, (BCE 1200). In India, the earliest Kirthimukha can be seen on the relief of the Amaravati stupa,” she added.

Even though several of the great deeds of lord Shiva have been immortalised in sculptures, the defeat of an asura called Jalandhara is seen only in a few places, according to R Gopu of the Chennai-based Tamil Heritage Trust. Speaking on ‘Jalandhara Story in Pallava Sculpture’, Gopu said, “Themes like the ‘Descent of the Ganga’, ‘Gajasamhara’, ‘Annihilation of Tripura,’ are quite popular in Pallava sculpture, and continued to be popular in the subsequent Chola, Vijayanagara and Nayak eras. But the defeat of Jalandhara is only seen in a few Pallava temples in Kancheepuram. Among these, several aspects of the episode are depicted in the Kailasanatha temple in Kancheepuram.”

Indian religious beliefs and practices had contributed to South and Southeast Asian cultures. The deities, demons and the aesthetic forms that flourished in India were transmitted to south and Southeast Asian countries through trade and commerce.

“As in India, religious images of demons have been observed in temples and other religious edifices of South and Southeast Asia since the 2nd century BCE. They are seen in stone, wood and metal. Demons are one of the most diverse subjects in art history of South and Southeast Asia in terms of style and form. They have provided a source of artistic inspiration because of their peculiar characteristics and the mysticism surrounding them. They appear in many different forms. So different aspects of demonology have to be viewed in a South and Southeast Asian perspective for their comprehensiveness,” said Preeta Nayar, of the Department of Archaeology, University of Kerala, in the concept note of the webinar.

“The study of demonology requires a deep understanding of the cultural development of humans and religions. A comprehensive study on demons consisting of well-known as well as lesser-known characters in sculptural art from a pan-Asian perspective was the idea behind the webinar,” she added.