- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Budget 2024-25

- Business

- Series

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- Budget 2024-25

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

Fund shortage, internal conflicts amid tall claims cripple Sanskrit studies

In Mani Ratnam’s Bollywood movie Guru, actress Aishwarya Rai dances to ‘Barso re megha’ song atop a historical monument located in Melkote, Karnataka. The picturesque Raya Gopura, an unfinished monument built during the Hoysala dynasty rule around the 10th century, on which she stands, overlooks a series of deep stepped temple tanks and farmlands on a hill. The Raya Gopura even features...

In Mani Ratnam’s Bollywood movie Guru, actress Aishwarya Rai dances to ‘Barso re megha’ song atop a historical monument located in Melkote, Karnataka.

The picturesque Raya Gopura, an unfinished monument built during the Hoysala dynasty rule around the 10th century, on which she stands, overlooks a series of deep stepped temple tanks and farmlands on a hill.

The Raya Gopura even features in Rajinikath’s superhit movie Padayappa where he gets his daughter married to the man she loves.

Melukote, a historical temple town of archaeological importance in Karnataka’s Mandya district located about 150 kms from the state capital, is a famous shooting spot.

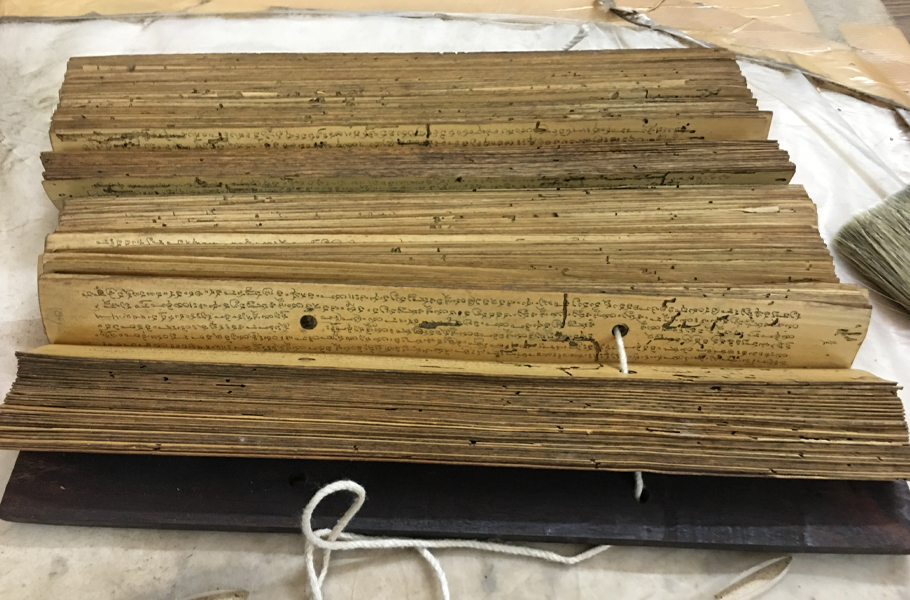

But behind the monument lies the efforts of a Sanskrit Research Academy that not many know. The Academy was established in 1977 to propagate the philosophies of theologian Ramanujacharya (who lived in exile in Melukote) and to dig deeper into Sanskrit research across the spectrum from science and technology to mathematics and history and more. The institute is located two kilometres from one of the oldest Sanskrit colleges in the country, which houses over 1,000 centuries-old manuscripts.

The Academy, which managed to stay afloat for the last four decades with private donations from culture enthusiasts, philanthropists, and paltry government aids, is now fighting to survive due to fund shortages for research projects, not enough scholars and poor infrastructure to maintain historical manuscripts and books.

Several Sanskrit institutions across the country are facing a similar plight.

This, while the Centre has passed the Central Sanskrit Universities Bill, 2020, and spending a whopping ₹643.84 crore on the promotion of Sanskrit in the last three years, when only ₹29 crore has been spent on five other classical languages — Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam, and Odia.

A centre in ruins

While the Bharatiya Janata Party-led government at the Centre is gung-ho about promoting Sanskrit and India’s rich history, the reality on the ground is starkly different.

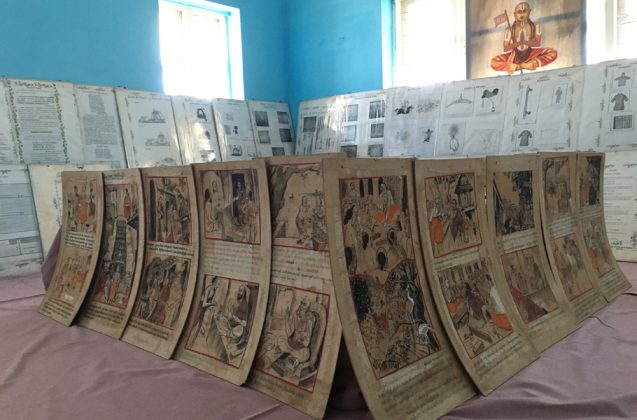

At the Sanskrit Research Academy, the racks in the manuscript division overflow with palm-leaf manuscripts, with not much space for new ones. Similar is the condition of the library. The researchers work out of a dilapidated building that requires repair. The museum material (artworks) are arranged on the floor of one of the rooms meant for gathering.

For the last three years, the Academy has been depending on crowdfunding for the upkeep of the buildings and research works due to the reduction of funds allocated by the government.

The management wrote multiple letters to higher education department officials, local administration, and the Chief Minister of Karnataka seeking funds to the tune of ₹4.5 crore as a one-time grant. They highlighted that it was needed for the upkeep of the library and cottages allocated to researchers, payout to contractual scholars, setting up an e-library, renovation of existing buildings. But all in vain, according to documents verified by The Federal.

S Kumar, who has been heading the institution for the past decade and is also the registrar of the Academy, says that though they have ambitious plans to collect over a lakh manuscript from across the country and build a repository in one place, and make it available online to scholars across the globe, the lack of funds hampers all plans.

“(Funds for) Paying salaries for staff alone is not enough. The government needs to allocate requisite funds for research and futuristic projects,” stresses Kumar. “If we ask for ₹4.5 crores, they give one-tenth of it. Largely, the money is spent on maintaining the 18 acres of land and paying (contractual) scholars who are not on rolls,” he adds.

It’s not just about funds. Some experts say even the availability of human resources is a constraint as the institute is located in a rural area. Besides, they opine that today most Sanskrit’ers are worried about their future livelihood more than the research work.

The Academy’s founding member and Sanskrit scholar MA Lakshmithathachar (84), however, is not happy with the way things are handled there.

“With respect to Sanskrit research, unless you make it relevant to the modern world, people will not be interested in it,” he says.

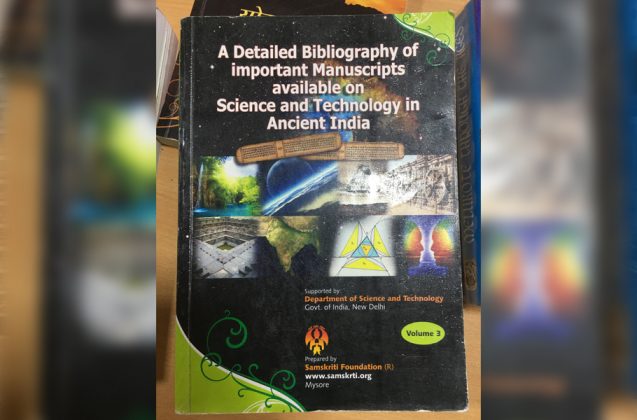

He says that is why he, through the private trust Samskriti Foundation, is bridging the gap between the past and present and making it appealing to the future world. “And I want the Academy also to do the same.”

The Samskriti Foundation is into mining information about many different topics as varied as aeronautics, Ayurveda, linguistics, and so on from various source texts in Sanskrit. But he also wants the Academy to do its bit for the greater good.

At 84, Lakshmithathachar sits comfortably in front of a big TV screen at his home wearing a headphone as he mentors students and researchers through Google video chat. Neither has his enthusiasm or work in Sanskrit gone down nor has his removal from the service dented his image, he says.

Mired in controversy

However, things did not go smoothly about a decade and a half back.

In 2004, the then deputy commissioner of Mandya, CN Seetharam, unauthorizedly took control of Lakshmithathachar’s office and the Academy. This was subsequently challenged in the High Court, which later observed that that the DC did not submit enough documents to take control of his office. The case was later disposed off.

A high-powered government committee in 2009 noted that though Lakshmithathachar was removed on the grounds of financial misappropriation, the person handling the finance during his period (S Kumar) was subsequently made the registrar. And that the circumstance under which Lakshmithathachar was removed remains questionable.

https://youtu.be/p7cqmoot7W4

Although he denies having started the Foundation or having taken any salary, Lakshmithathachar admits that he was part of it while in government service.

He says he was frustrated of being in a government setup and unable to do things due to red-tapism, and that prompted him to be part of a private trust and continue with the Sanskrit research and promotion in a better way.

Lakshmithathchar explains the difficulty in seeking funds. He says government officials look at it from a different prism. “If I go with a namam (trident mark on the forehead) and veshti (white dhoti) and seek funds for a project, officials think my work is restricted to purohitam (priest work) and conducting rituals, and nothing else.”

“When I proposed to bring out an encyclopaedia of Indian science and technology (through the ages) in 12 volumes costing around ₹6 crores, the government secretary said it was good but it had to be routed through Department of Science and Technology and prestigious institutions like IIT or IIMs,” he adds.

Lakshmithathachar, on the other hand alleges that the Academy is getting enough funds but not much work is being done after his removal.

Citing documents obtained through RTI, he alleges anomalies in the appointment of staff and fund management. The documents (a copy of which has been accessed by The Federal) are yet to be submitted to a new government committee seeking probe into his findings and seeking action into the previous committee reports.

The registrar Kumar, however, denies these allegations, saying after a writ petition was filed in the High Court questioning the finding of the committee report, an order has been passed in favour of the Academy.

“The high-powered committee was set up to say how to develop the institution. However, the committee failed to give us, the working members, an opportunity to explain and went ahead merely based on a former staff (Lakshmithathachar’s allegations) who is trying to tarnish the image of the institution,” he says. “The accounts are audited every year and the documents are available for public access.”

Besides, Kumar says that Lakshmithathachar’s image overshadowed the institution and people thought it was his Academy and not that of the government’s. “He could have achieved what he’s doing as part of the Foundation while he was part of the Academy. Instead, he chose to aid a private body and trying to tarnish the Academy’s image,” Kumar adds.

Things went from bad to worse for the Academy and in 2016-17, it was brought under the ambit of Karnataka Samskrit University and is no longer an independent body.

In 2017, the Mandya DC reportedly even wrote to the Department of Endowment, seeking the Academy’s eviction saying it operated without renewing the land lease period.

Institutions in a limbo

The state of affairs in other Sanskrit institutions across the country is no different. Staff shortage, fund crunch, lack of researchers and students are common complaints.

In a Lok Sabha reply in 2019, the government said 50% of the teaching posts in Sanskrit Universities remained vacant.

Recently, at Patna University (PU), only two students took admissions (until December) in the Sanskrit department against 40 sanctioned seats in three colleges. Similarly in Pataliputra University, nearly 87% of the Sanskrit seats remained vacant, according to reports. It’s the same story every year since 2016.

In Assam, the state government cited lack of funds as a reason to shut 99 aided Sanskrit learning centres along with state-run madrasas. The government cited lack of funds and the need to usher in “secular education” as the reason, while also adding that Sanskrit learning centres would become centres for studying Indian history and civilisation.

In Uttar Pradesh, after struggling to find enough students willing to pursue Sanskrit, the government last year ordered shutting of some Sanskrit institutions and clubbing some with others. In 18 institutes, there were no professors at all. Media reports indicate some schools were run with peons managing the affairs.

In Madras Sanskrit College, for a sanctioned 24 PhD scholars, wherein six professors would be required to handle four scholars each, only 18 scholars are there.

Dr TP Radhakrishnan, principal at Madras Sanskrit College, says the interest is dying down among students so much that Sanskrit is their last option.

Lakshmithathachar too concurs, saying while not more than 30-40 scholars are available across the world for vishishtadvaita (a branch of Vedantas) research, he finds it difficult to entice them to come and work or live in Melukote, a rural area, without the requisite infrastructure.

“Had the institution been set up in a city like Bangalore or Mysore, it would have gotten its due recognition and money long ago. I did a mistake by setting up in a rural area,” he rues.

To improve the scenario, Radhakrishnan says we need to improve the intake quality and that comes with rigorous promotion of the language backed by opportunities for those who graduate.

“Then scholarships and stipend should be given to PhD students on the lines of other UGC recognised courses (₹3,000 a month at least),” he says. “And lastly, the government should hire more experts to teach.”

If not, Radhakrishnan and others fear that the study of Sanskrit could in a matter of time become like the Raya Gopura—an unfinished monument with only glamour value.

(An earlier version of the copy mentioned that Lakshmithathachar was expelled from the Academy in 2004. We apologize and regret the inconvenience caused.)