- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Forgotten healers: When barbers in TN were also medicinal experts

In the 17th-18th century, hairstyling was a traditional profession taken up mostly by a community, called Ambattans, who also acted as healers following the Siddha practice.

When matinee icon Rajinikanth, in his 1979 film Aarilirunthu Arubathu Varai (From Six to Sixty), discovers the secret love affair of his sister, he asks her what the boy does for a living. As the girl hesitates to respond, the brother asks, in jest, if her lover is a barber. In cinema halls across the state, this sparked off bouts of laughter every time the film was screened. For, that is how...

When matinee icon Rajinikanth, in his 1979 film Aarilirunthu Arubathu Varai (From Six to Sixty), discovers the secret love affair of his sister, he asks her what the boy does for a living. As the girl hesitates to respond, the brother asks, in jest, if her lover is a barber. In cinema halls across the state, this sparked off bouts of laughter every time the film was screened. For, that is how the society looks at barbers, often using the word ‘barber’ as an adjective of ridicule. The same society, however, is in awe of ‘hairdressers’ in swanky ‘hair salons’ who come from different caste groups and earn well, having even undergone specialised academic training in hairstyling.

But barber shops in Tamil Nadu earlier used to be more of a hangout spot for a generation nurturing interests in politics and films. Sadly though, while these shops were celebrated, the barbers were not.

In the 17th-18th century, hairstyling was a traditional profession taken up mostly by a community called Ambattan, colloquially known in Tamil as Naavidhar. They used to remove hair from the head, face, underarms and even private parts, besides acting as healers following the Siddha practice. Male barbers were called Naavidhar while female barbers were known as Maruthuvachi.

A novel tracing history

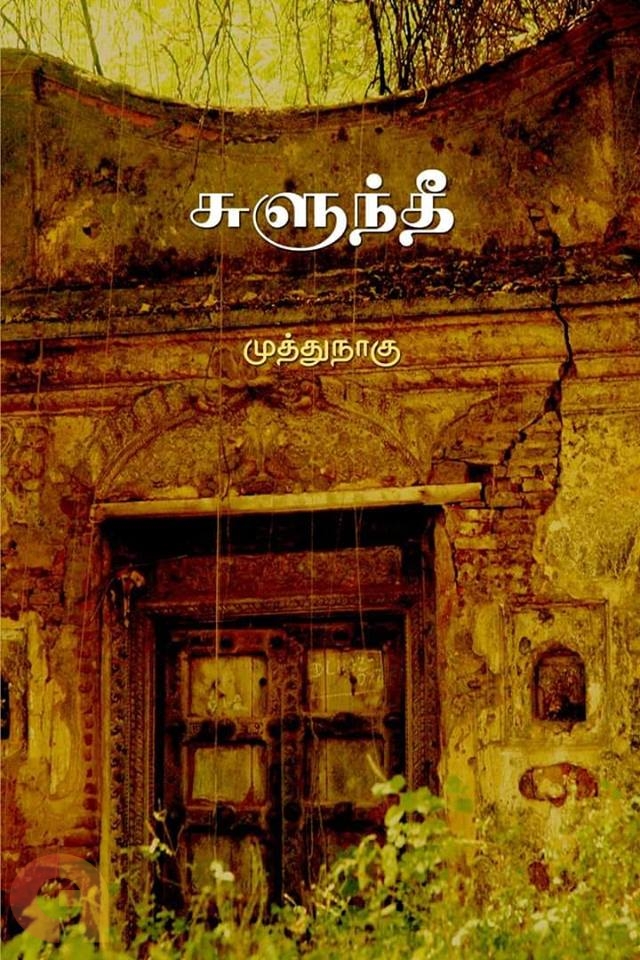

While much of their history faded away due to the political turmoil in the region — with the change of kings and the arrival of the British — a novel titled Sulunthee in Tamil by Theni-based journalist and photographer R Muthunagu traces several customs and traits of the profession in his 480-page book.

In those days, poor people, including barbers, used firewood from a tree called Sulunthee as firewood in kitchens and to light up their homes as well. Muthunagu says firewood became a symbol of the poor and hence the title of the book.

The novel is about Raman, a barber-healer in the administration of Kannivadi polygar, appointed by the Nayak rulers. Raman dreams of making his son Maadan a warrior and not a barber like him. However, the administration’s jealous commander prevents this. After Raman dies, when the Kannivadi administration assigns his job to his son Madaan, the commander, using his malicious ways, denies Madaan the job.

Unable to fulfil his father’s dream and unable to do the work that was passed on to him, Maadan sets a wrestling challenge wherein he would go back to being a barber if he loses, but that he should be made a warrior if he wins. The plot unfolds with the contest.

The author, within this fictional tale, blends the history of the Ambattan community, especially their medicinal prowess. Throughout the novel, the author explains their skills, citing at least 50 examples.

The medical supervision they provide was called ‘panduvam’. So they were also called ‘panduvar’. The panduvars had a knack for diagnosing a disease just by observing one’s breath — from which nasal opening, air comes and goes out. They earned a name for growing one’s ear by gently pulling the earlobe, because in those days, Tamil women needed bigger ears as per their one’s height and weight, so that they could wear big ear studs. The panduvar also knew how to administer cobra’s venom as an antidote to other snake bites.

Bans and wane of barbers

Coming from a family of traditional healers, Muthunagu says that it was after the arrival of the British that panduvars started losing significance, for the British restricted the sale of toxic chemicals like lead, mercury and sulphur.

“Only a siddha practitioner approved by the association of siddha doctors could buy those chemicals then, particularly sulphur, because it is an explosive material. Senthooram (a metallic compound) was the highest medicine in that traditional healing. It required sulphur. During the period of Nayaks, many who revolted against Nayaks took the help of panduvars to create explosives,” he said.

The novel is situated in Madurai in the 18th century when the state had faced attacks from seven corners — the French, the Dutch, the British, Arcot Nawabs, Nayaks, Tipu Sultan and Marathas. However, the predominant clash was between Nayaks who spoke Telugu and the Tamils.

“In those days, each community had its own mutts. There are Vaishnavite (followers of Vishnu) mutts and Shaivite (followers of Shiva) mutts. The existence of such mutts differ from place to place. In one place, the barbers would be Shaivite, in others, Vaishnavite. But mostly, the barbers were Vaishnavites,” Muthunagu says.

The heads of these mutts travelled throughout the year. During these trips, called ‘sanjaaram poguthal’, they met all kinds of communities and tried to learn their skills. Since the barbers’ work like cutting the hair or nails, were hygienic acts, they innately had a sense of cleanliness and hygiene. So, the mutt heads chose the barbers as their ‘sishya’ (student) and transferred the medical knowledge to them, he says.

“When Nayaks came to know that the rebellions had the help of panduvars in making explosives, they started killing the panduvars. That was how 23 Shaivite panduvars in Palani were killed. But there was no written record for this claim. People depend on the oral renditions of this cruelest act for hundreds of years,” he says.

Oppression under caste system

The Nayak administration was also known for excommunicating people, especially those born from extra-marital affairs, those who married out of their caste, men who married women by paying money, men who married women at night and people who kept arms like knives (in those days, only warriors and barbers were permitted to possess knives). And people were ordered not to take up any other profession other than their traditional one like barber, washerman, etc.

“In those days, barbers were not given any wages. Instead they were given land as subsidy and grains. Those lands were owned by caste Hindus. If they ask the barbers to leave the land, the latter were required to leave,” says Muthunagu, explaining how this always led to an insecure environment.

Also read | A common Tamil thread could have bound Keeladi with Harappa

“When a king or a ruler from another country captures the country the barbers live in, the highest people in the caste hierarchy like warriors and temple priests, join hands with the new ruler. One could not expect a new ruler to follow the practices of the old ruler like giving lands as subsidies. So, the powerful people like warriors and the priests usurped the lands of the barbers and washermen. During this period, the caste system became more and more strong,” the writer observes.

Though most of the panduvar were from Ambattan community, a Backward Class (BC) then and now Most Backward Class (MBC), there were also Kudumbans, an offshoot of Pallar community, a Scheduled Caste (SC). Only in Kanyakumari, since it was earlier with Travancore kingdom, the barbers were from the SC category.

Over a period of time, when the Nayaks’ oppression of Panduvar increased, they threw their literature into fire and in rivers.

“Besides individuals, these kinds of healing and medications were once taken by the institutions like mutts. The mutts provided three kinds of services to the people — yoga, satsang and vaidya,” says historian Rengaiah Murugan.

Mutts provided medical services free of cost through their ‘Dharma Aaspathiri’ (charitable hospital) and most of the medicines prepared were by using herbs found in the country.

“Sulphur was also used to build wells. Since it had an explosive nature, the British banned these chemicals. After Dravidian movements started, these mutts also lost their sheen,” says Murugan.

Then came the kings and the British

Before the arrival of the Nayaks, the lands were with the temples. All the people had a stake in those lands without caste differences. It was during Nayak rule, the lands were brought under kings, he says.

The kings wrested the lands from the locals and gave it to their people, who had migrated with them.

These people discriminated against the locals based on the kind of work they did. Since each caste had its own barbers, a barber from one community would not serve people from other communities. “That’s how the barbers, dhobis, carpenters were excommunicated. This tradition continues even today in some parts of the state,” Murugan says.

K Ragupathi, assistant professor of history, Thiru Govindasamy Government Arts College, Tindivanam, says the healers turning into barbers was a world phenomenon.

“The traditional healers were present once all over the world. Their main job is medicine. They were well versed in performing surgeries. Before surgery, the body hair should be removed. In those periods, the shaving knife was available only with these healers. Hairdressing was considered a healthy habit. So, the healers also performed hairdressing. There were no differences between a doctor and a barber then. Hence they were called ‘barber-surgeons’,” says Ragupathi, who had done research on baber-surgeons in Tamil Nadu.

Circa 1540, in Europe, an act was brought by academically qualified medical professionals to distinguish between surgeons and barbers. That brought about an end to barbers performing surgery, he adds.

Also read | Reliving childhood: 40 years of Azhiyaatha Kolangal

“But in Tamil Nadu, the traditional healers performed three other kinds of jobs namely, temple priests, hairdressing and performing funeral rites,” said Ragupathi.

Another reason for barbers’ excommunication was because they cut dead bodies to learn anatomy, says Raghupathi. But since religions considered the living body as a holy thing, the barbers became ‘unholy’.

Modern medicine or allopathy, brought by missionaries on the arrival of the British, sounded the death knell for barber-healers.

“Since allopathy provided fast-cure, people preferred that and the country medicine declined gradually,” Raghupathi says.

And with that, the barbers lost the equal status they enjoyed with medicine practitioners and are not looked up to in society.

As for Rajinikanth, who in all likelihood did not intend to insult the barber community, made up for the scene in Aarilirinthu Arubathu Varai the next year itself, donning the role of a barber in Johnny.