- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

Back to chasing its steel dream, Odisha faces risk of another people's movement

Last December, Odisha chief minister Naveen Patnaik was quite ebullient at the annual convention of Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce & Industry (FICCI). “I am happy to note that the investor sentiment towards Odisha is extremely encouraging. Even during the difficult COVID pandemic time, I am happy to inform you that Odisha has been able to attract new investments of over ₹1...

Last December, Odisha chief minister Naveen Patnaik was quite ebullient at the annual convention of Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce & Industry (FICCI).

“I am happy to note that the investor sentiment towards Odisha is extremely encouraging. Even during the difficult COVID pandemic time, I am happy to inform you that Odisha has been able to attract new investments of over ₹1 lakh crore across multiple sectors,” he said.

The state was fast emerging as a manufacturing hub of eastern India, he said, adding that it was ranked number one in attracting investments during April-September 2019 and was poised to retain the position.

Naveen had more reasons to be happy. Four months later (March 2021), as the country was tackling the second wave of Covid-19, global steel leader ArcelorMittal Nippon Steel inked a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with the Odisha government for setting up a 12 million-tonne integrated steel plant in Kendrapara district at a proposed investment of ₹50,000 crores.

In April, South Korean ambassador to India Shin Bongkil informed that the steel behemoth POSCO was planning to make one of the largest FDI in the history of India with an investment of US$12 billion (88,500 crore) to set up an integrated steel plant in Odisha.

Bed of roses

Observers are not surprised though. They believe that investors are bound to head back to Odisha. “With the state’s rich mineral deposits, if investments don’t come today, it will come tomorrow,” says activist and futurist, Charudutta Panigrahi.

Odisha’s minister of state for energy, industries and MSME, Dibya Shankar Mishra reasoned that, besides huge raw mineral deposits—the coastal state accounts for 28% iron ore, 24% coal, 59% bauxite and 98% chromite of India’s total deposits—there are several other factors that attract investors to the state.

“Over the last two decades, through progressive policies and stable governance, an industrial ecosystem has evolved and the steel sector has boomed in the state of Odisha under the leadership of our chief minister, Naveen Patnaik,” Mishra tells The Federal.

“Odisha has to be the most preferred destination for an investor for its rich mineral resource base, availability of water in plenty (11 percent of the country) and a concerted effort at creating a huge skilled manpower base. Coupled with this, the state of the art industrial infrastructure and industry friendly policies as well as political stability add to its attractiveness as an investment destination,” he argues.

Mishra says the government’s focus sectors are steel, aluminum, textile/apparel, sea food, petrochemicals and IT and electronics. However, the steel sector has attracted the maximum investment to Odisha.

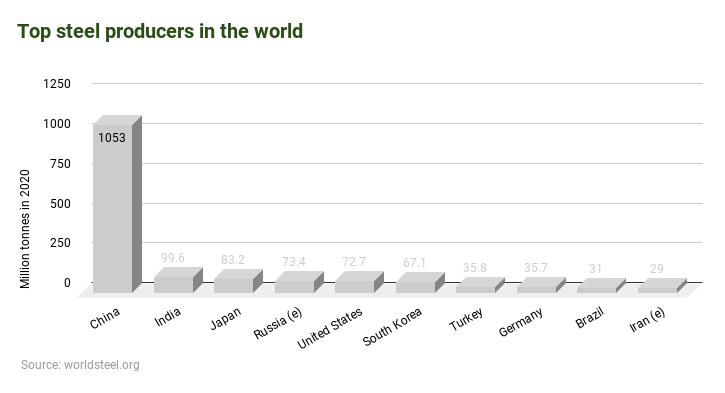

Also, at 99.6 MT in 2020, India was the second-largest producer of crude steel in the world after global leader China. Odisha, with approximately 20 MT, is India’s leading steel producing state.

With big ticket investments for greenfield projects—which also includes JSW Steel’s proposed 13.2 million tonnes per annum (MTPA) plant at an investment of ₹53,000 crores—and many existing facilities (Tata Steel, JSPL to name a few) going for capacity expansion, Odisha seems to be on its way to enhance steel production to 100 MTPA, which is one-third of the National Steel Policy’s envisioned capacity of 300 (MTPA) by 2030.

Odisha’s steel and mines minister, Prafulla Kumar Mallik says: “We are on the right track. Odisha will achieve the 100 MTPA target even before 2030.”

According to Mallik, Odisha has already signed MoUs for approximately 94 MT steel a year.

Sources in his department said, in the steel sector, the approved investment stood at roughly ₹3 lakh crores (greenfield and brownfield projects combined).

The state also figures prominently in the central government’s ambitious Mission Purvodaya scheme, unveiled in January, which aims at accelerated development of eastern India through integrated steel hubs.

A race with hurdles

However, many including Panigrahi believe that translating the MoUs and investments into projects on the ground may not be that easy.

“We welcome the investments in the iron and steel sector but with clearly laid out benefits for the local communities,” Panigrahi asserts.

Prashant Paikray, spokesperson of Anti-Jindal and Anti-POSCO movement, is much more uncompromising.

“We don’t want any project here. Earlier we were against Posco, now we are against JSW’s project,” he declares, citing the lack of rehabilitation for people displaced decades ago for the Hirakud and Rengali dams and those affected by the Indian Oil Corporation’s (IOC) refinery project in Paradip.

“If the government is serious about setting up industrial projects, let it do that in a no man’s land,” Paikray suggests.

He also notes that most of the labourers at the IOC are from outside, very few locals get to work in the project. “If the local people are not provided with jobs or alternative sources of livelihood, why would one part with his land and for what?” he asks.

Noted environmental activist, Prafulla Samantara is sharper, saying: “At no cost, Odisha’s interest, climate justice or sustainable livelihood of the marginalised people in particular and the farmers in general will be allowed to be compromised.”

He adds that the aim of the industrialists and the “insensitive governments is to completely destroy the state’s future”.

Land acquisition and agitations

Resistance and agitations against industrial projects have been a common trait since the 90s when Odisha went for massive industrialisation with the advent of liberalisation and economic reforms.

Local communities, often backed by NGOs or political groups, have resisted the acquisition of land against their wishes or against the poor rehabilitation and compensation given to them.

Dismissing the government’s enthusiasm over the surge in investments, Congress leader Arya Kumar Gyanendra says big investors were only eyeing Odisha’s natural resources for profit.

He then recalls Odisha’s past experience with Posco and ArcelorMittal, and says: “The Odisha government should stop patting its own back. It’s the same government which had failed to provide mines and required land for which both Posco and ArcelorMittal had shelved their projects.”

Although steelmakers in public and private sectors have a significant presence in Odisha, foreign firms have so far failed to establish any major manufacturing capacity in the state.

In 2006, ArcelorMittal had planned to set up a similar 12 MTPA greenfield plant in Odisha’s Keonjhar district. However, it abandoned the plan in 2013 on account of delays in the land acquisition process and lack of assurance on a captive iron ore mine at that juncture.

Posco too, had initiated the process for its (12MTPA) facility near Paradip in Jagatsinghpur district. Till 2013, the state government managed to acquire only 2,700 acres and transferred 1,700 acres as against the original requirement of 4,004 acres.

According to former Oidsha chief secretary, Gokul Pati, the site allotted to Posco was mostly government land occupied by the locals, who were largely into farming, especially of betel vines. Private land was minimal. The government had acquired the land and offered ex-gratia to the affected families under compensatory grounds but many people were not happy and the resistance continued.

The final blow came with the change in mining laws by the Centre in 2015, which made it mandatory for companies to go through the auction route for captive mines. Earlier, it was on a nomination basis. The same year Posco suspended its project in Odisha.

If Posco and ArcelorMittal left after finding it difficult to set base, Tata Steel met with a major roadblock when 13 tribals, including three women and a 12-year-old boy, were killed in a police firing during a protest against the setting up of Tata Steel plant in Kalinganagar in 2006.

Over the next many years, the company held several negotiations with locals and tribals, provided rehabilitation and resettlement to the families of victims. It was only nine years after the incident that it was able to set up a steel plant in Kalinganagar in 2015.

New policies pave the way

In 2006, the Odisha government also came up with a Rehabilitation and Resettlement (R&R) Policy that improved the compensation package for displaced people.

As per the policy, affected families would be taken into confidence before their land is acquired and an adequate compensation would be given as per norms. Those set to be displaced would also be resettled in an appropriate manner. The policy also assures jobs to locals in the industries which come up in the areas, but activists have decried that this rule is violated. As per the last update in 2018, affected families were set to get upto ₹8.5 lakh as one-time settlement if they were to lose their homestead and agricultural land for industrial purposes.

Former chief secretary Pati says Odisha’s R&R policy is more ‘pro people’. “It’s one of the best in the country,” he claims.

However, according to a resident of a village next to the site where earlier Posco was interested to establish its project, some of the locals whose betel vines (on government land) were dismantled accepted compensation.

While many refused to accept the same, there are some who are yet to receive their compensation. “They feel frustrated,” he says.

Further, the state government has been improving its policies for industries. In February this year, it enhanced the land acquisition ceiling for industries. Private companies can now purchase 500 acres in rural areas and 100 acres in urban centres.

On the environment front, experts say today there are stringent environmental rules. Environment was an issue in case of the Niyamgiri hills (for Vendanta’s Lanjigarh project). It is mandatory for every project to take environmental clearance. Over the past years, several industries have been penalised for violating environmental rules. But steel majors do not see these as a deterrent.

Observers say these developments triggered a beeline of investors to Odisha. A year after Tata established its steel plant, JSW Steel in 2016 sent a proposal for a mega project in Paradip, the same place where POSCO had planned its plant. Soon, others followed.

What the future holds

But what observers question is whether the new rules will be followed in letter and spirit and locals and tribals will be benefitted from the industries.

According to Pati, who was also the industries secretary, steel industries in India are experiencing a substantial increase in demand due to massive infrastructure spending as a result of the stimulus provided by the countries affected by Covid-19 pandemic.

Mineral rich states like Odisha have, therefore, an excellent opportunity to attract investment in the sector but they need to activate a governance framework to encourage the potential investors while at the same time enhancing long term sustainability with emphasis on public goods and welfare.

According to Sudhir Patnaik, editor of Samadrusti, both Prime Minister Narendra Modi and chief minister Naveen Patnaik’s policies on mines and industries are the same.

“Unfortunately, for the ruling political leadership across the country, the tribals who have protected the natural resources of the country for generations are the enemies of such resources and also development. They can be dispensed with. Such a development paradigm has been legitimised by the civilised society. As a result, the ruling leadership assumes that their actions have got the backing of the larger society. The silence of the mainstream society is indeed painful,” he says.

Senior journalist Nilamadhab Nayak who has reported extensively on the tribals and their displacement in Kalinganagar, says, “Displacement has disturbed the unity among the tribals. Many of them have been won over by companies. Over the years, their voice has thinned, their opposition has of little meaning.”

On the other hand, he says, “The Congress and the BJP (who are in opposition) failed to take up their issue.”

He further points out that the tribal displacement issue “has no impact on the electoral fortunes of the state. We have seen it in Kalinganagar.”

Stating that there is already a rise in “woke” capitalism, Panigrahi feels in the days to come, the companies will try to play a decisive role in the policy making of the state.

“Here comes the role of the civil society, which, unfortunately, is entirely nonexistent and apathetic in Odisha. In the absence of the civil society, companies will make up for it and have a large say in the development of the concerned district of their mining operation. As a result, there is a scare that the interest of the local tribes will be compromised. In the past we had very bad experiences,” he says.

A BJD leader who did not wish to be named however dismissed such concerns.

“Every action and policy of the BJD government is in the interest of the people and everyone in the state knows that CM Naveen Patnaik is committed to their welfare. They also know that industries are essential and will benefit them. The government tries its best to use maximum government land for industrial purposes. As and when private land is required, the affected families are taken into confidence and adequately compensated with as per the R&R policy. All this is done in a fair and transparent manner and the people are happy.”

But activist Paikaray, however, reveals that people have their own plans. “The locals are ready to hit the streets and launch a people’s movement,” he says with a steely determination.