- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

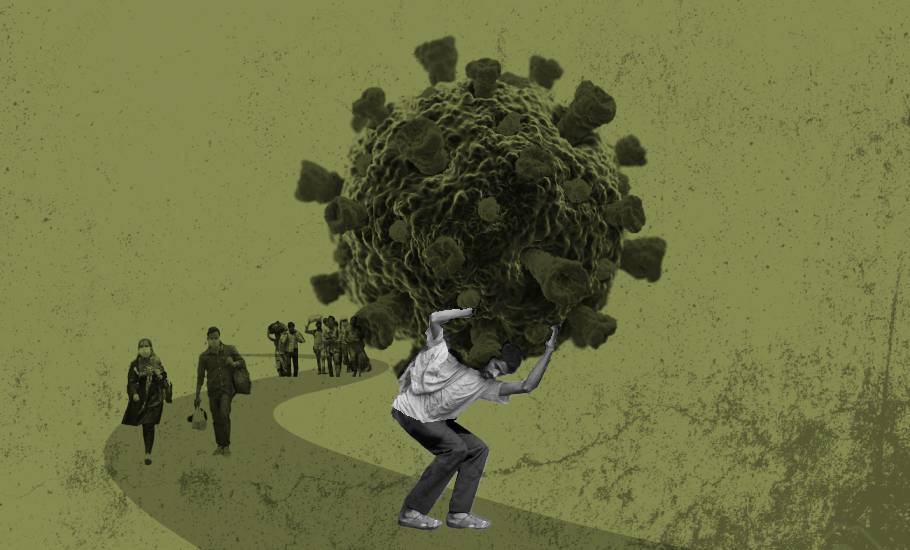

Back in their villages, only hope for migrants is UPA-era MNREGA

More than any long term measures, the migrant workers seeking immediate relief after their recent nightmarish experience are pinning their hope on the MNREGA, once ridiculed by Prime Minister Narendra Modi as a living monument of the failure of the erstwhile Congress-led UPA government.

Tucked away in the rough terrains surrounded by small hillocks, Uparbatri, Dumdumi and Bongabari are just dots on the map of West Bengal. Every year hundreds of youths from these villages quietly migrate to big cities in search of livelihood as the dry rain-fed fields here often do not yield enough to sustain the staple dietary needs of the villagers. The exodus would have gone unnoticed, as...

Tucked away in the rough terrains surrounded by small hillocks, Uparbatri, Dumdumi and Bongabari are just dots on the map of West Bengal.

Every year hundreds of youths from these villages quietly migrate to big cities in search of livelihood as the dry rain-fed fields here often do not yield enough to sustain the staple dietary needs of the villagers.

The exodus would have gone unnoticed, as it has been for years, but for the COVID-19 infused reverse migration, which has exposed the dearth of livelihood avenues in rural India.

Since Saturday, the villages suddenly shot into prominence after six youths from there died and several others were injured in a road accident in Uttar Pradesh while trying to flee hunger in Rajasthan, where they migrated a few months ago so that they could earn enough to feed themselves and their families back home.

Tragedy and despair

On Sunday, even before the bodies of the deceased reached the villages, district magistrate Rahul Mazumdar and minister for Western Region Development Santiram Mahato visited the bereaved families and handed over cheques of ₹2 lakh each.

The mortal remains reached the villages on Monday morning. As the ambulance carrying three bodies reached Uparbatri, all restraint let loose before the outpouring of grief.

Arati Rajowar, wife of one of the deceased, Swapan Rajowar (22), was inconsolable. On Thursday (May 14), Swapan had called his father to inform him that he along with a group of others had decided to walk home. Swapan was working at a marble factory near Jaipur.

The next day, he called again to inform them that they had reached Uttar Pradesh and boarded a Patna-bound truck. During the conversation, he was very excited about the home-coming and kept on saying how much he was missing his two-and-a-half-year-old son.

Early on Saturday (May 16), the tragic news came. The police informed that the truck in which they were travelling met with an accident, in which four persons from Purulia district died, including one Ajit Mahato of the village.

The next day, the police broke the news that Swapan and Dhiren Mahato, from the village too had died in the accident while another youth Gopal Mahato sustained injury.

The news devastated the villagers.

A similar pall of gloom descended over other two villages struck by the tragedy.

The migration of fear

Sleep has eluded Uma Karmakar, mother of Shivram Karmakar, since she got the news of the accident. One of her sons, Shivram (28), broke his right ribs in the accident and is now undergoing treatment at Purulia Sadar hospital.

Her two other sons are stuck in Tamil Nadu and Gujarat.

“With a very heavy heart, we let our sons migrate to far off places so that they can earn a decent living. No mother wants her children to be away from her, but what is our option? What will we eat if they don’t go out to work?” she said over the phone of one of her neighbours.

When the DM and the minister visited their Bongabari village, she told them to create enough job avenues in the villages so that no one needs to venture out for a living.

From his hospital bed, Shivram says after what he had experienced this time, he would think a hundred times in the future before migrating to far off states to work.

“Henceforth, I will take up a job only if it is within the state or at the most, in neighbouring Jharkhand. Otherwise, I will have to look for some odd jobs in the village itself,” he said.

MNREGA — the panacea

Shivram was working at Balaji Garden, a sprawling marriage venue, near Jaipur. He said after being discharged from the hospital, he would first apply for a job card under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MNREGA).

The small plot of land the family owns is not very suitable for agriculture. There are vast swathes of land in Purulia, Bankura, Jhargram, Birbhum, West Burdwan and West Midnapore districts of the state which cannot produce anything naturally.

Last week the state government identified 50,000 acres of barren land in these six districts of the state for income-generating activities like horticulture and pisciculture involving locals.

More than any such long term measures, the migrant workers seeking immediate relief after their recent nightmarish experience are pinning their hope on the MNREGA, once ridiculed by Prime Minister Narendra Modi as a living monument of the failure of the erstwhile Congress-led UPA government.

Nurul Islam, who has cycled about 2,300 km from Maharashtra’s Mulund to reach home at West Bengal’s Kaliachak in Malda; Narayan Baidya, who traversed almost 2,000 km on foot from Pune to reach his village Mayurhat in Bengal’s Nadia district; or Amar Mudi, a construction worker, who has returned to his village in Purulia from Bihar’s Patna, walking over 400 km, are all seeking employment guarantee under this scheme instead of regular jobs in far off places.

This is a general trend across the country.

“So much demand for the MNREGA works has never been seen before,” says Jean Drèze, the renowned economist and social scientist who works as a visiting professor at Ranchi University.

Talking to The Federal over the phone he said large-scale employment should be given to migrant workers, who have returned home, under the MNREGA to offset their financial loss.

“The plan should be put in place for continuation of MNREGA work even during the monsoon by getting people involved in plantation work, land leveling and even road construction,” he says.

Ironically, even Modi has now realised the importance of the scheme he had never missed an opportunity to take a dig at.

Too little, too late

To provide a fillip to employment, his government has decided to allocate an additional ₹40,000 crore under MNREGA over and above the ₹61,500 crore budgeted earlier.

The scheme, however, has its own inherent limitations. For example, only unskilled labourers can be hired under the scheme, and that too for 100 days of employment (per household), within 15 days of requisition. A failure to provide employment within the stipulated time frame has to be compensated through an unemployment allowance. Even the average daily wage rate of ₹210.86 is lower than the minimum wage rate fixed by the states.

In view of the present rural distress and growing demand for jobs, the MNREGA needs to be restructured by providing more than 100 days of employment and expanding its ambit by including new areas such as MSMEs and cottage industries.

Unfortunately, apart from the additional fund allocation, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman did not make any announcement to make the scheme the fulcrum to provide jobs to migrant workers.

The allotment according to the finance minister’s own admission would create 300 crore-person days work in total. Given the fact that there are 13.62 crore job card holders in the country, this would mean that the average days of employment provided per household will be less than 25 days.

With more migrant labourers like Shivram set to queue up for the job cards, the current allocation will be further too less.

“The allocation is not adequate for the whole year. But I hope the government will provide more funds,” Drèze says.

If he does not succeed to get enough work under the rural job scheme, Shivram says he would have no other choice but to migrate again, a prospect he shudders to even think of.

(This story is part of a series on Migrant Workers)