- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

A Padma Shri winner’s search for the dying languages in the Andaman Islands

Located southeast of the Indian subcontinent in the Bay of Bengal, the Andaman Islands are a cluster of about 550 islands, rocks and outcrops running from north to south. Even though historians and scholars have been visiting the islands for their research, details about the islands’ people and their rich culture are not much known to the outsiders. In 1996, veteran filmmaker Priyadarshan...

Located southeast of the Indian subcontinent in the Bay of Bengal, the Andaman Islands are a cluster of about 550 islands, rocks and outcrops running from north to south. Even though historians and scholars have been visiting the islands for their research, details about the islands’ people and their rich culture are not much known to the outsiders. In 1996, veteran filmmaker Priyadarshan made Kaalapani, a Malayalam feature film based on the historical events that took place in the Andaman Islands during the early 20th century AD.

The dreaded Cellular Jail in Port Blair in the Andaman Islands where many Indian freedom fighters were incarcerated by the British became popular after the movie turned a box-office hit in Malayalam, and remade it in many other Indian languages subsequently. Even though the popularity helped increase the tourist inflow to the Islands, the cultural and social multitudes of the people in the Andamans remained an enigma.

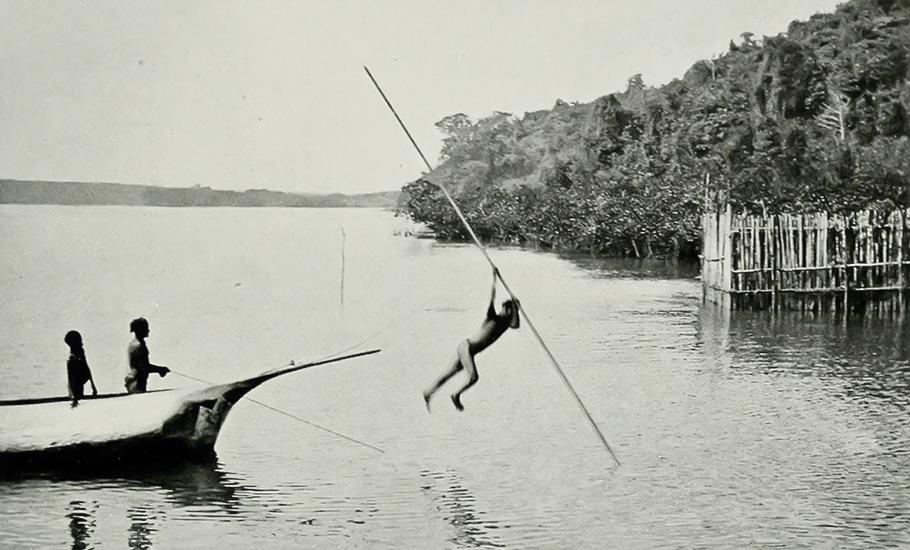

Geneticists claim that the Great Andamanese, an indigenous people of the Andaman Islands, are survivors of the first migration from Africa that took place 70,000 years ago. Considered the last representatives of those who lived during the pre-Neolithic times in Southeast Asia, scholars believe that they are possibly the first settlement of the region by modern humans.

The Andaman Islands are home to four ancient tribes, the Great Andamanese, Onge, Jarawa and the Sentinelese. Despite being a culturally rich society, the language and people’s way of living are in significant danger today, according to linguist and social scientist Anvita Abbi, who has carried out first-hand field research on all the six language families of India, extending from the Himalayas to the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. “While the languages of Onge and Jarawa are transferred intergenerationally, the language of Great Andamanese is moribund with four semi-speakers left as of 2022,” said Anvita, who was the first guide for a PhD on Jarawa, another endangered language of the island.

Also read | The atlas of lost islands in a rapidly drowning world

Anvita Abbi has been working on tribal and endangered languages since 1977. It was after conducting thorough research and innumerable visits to the islands that she documented Great Andamanese, the language of the Andaman Islands. A lot of fieldwork in the Andaman Islands was challenging. It was in 2001 that she first visited the Andaman Islands to conduct a pilot survey of the languages spoken in Great Andaman and Little Andaman. She saw water snakes more poisonous than any cobra, crossed narrow creeks laden with crocodiles, and lived in shanties regularly visited by snakes, scorpions and leeches. It has been more than two decades, and her attempt to preserve the languages of the island is on. The biggest challenge, however, came in the form of the language itself which was on the brink of extinction with less than nine speakers who were sort of semi-speakers, who had stopped speaking in their heritage language.

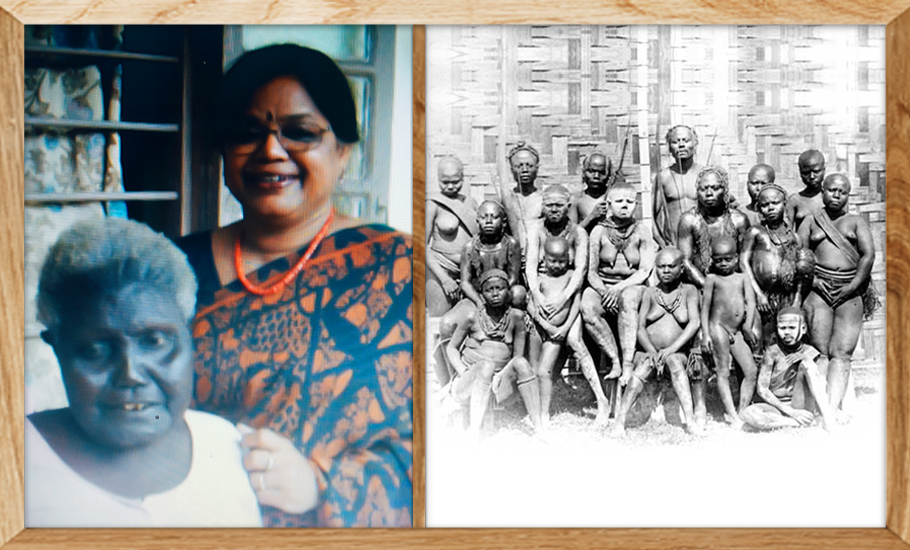

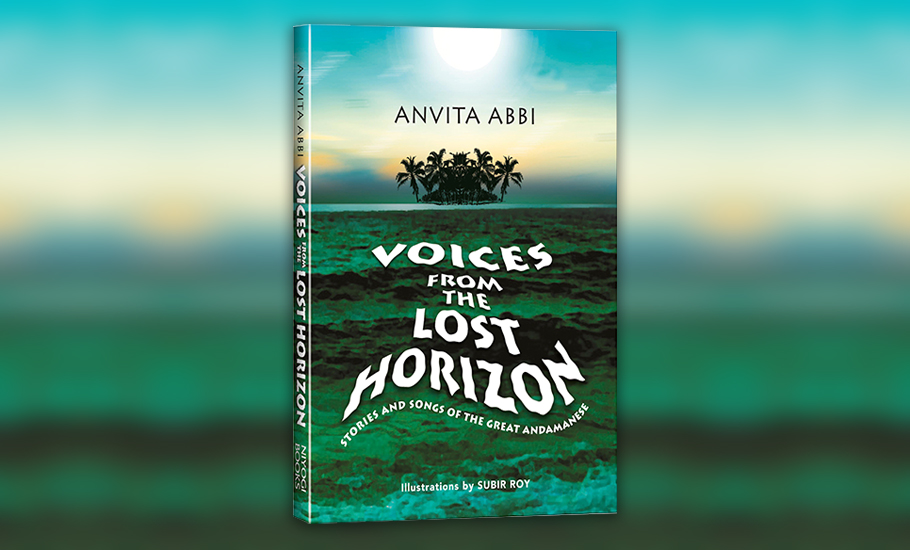

“No one had heard any story for the last 40 years nor had anyone sung in Great Andamanese languages. In such a scenario, my constant struggle was to motivate them to remember and narrate or sing. Boa Sr, the main singer of the 46 songs given in my latest book Voices from the Lost Horizon (2021) obliged without much ado as she remembered songs but extracting narrations and grammatical structures was really challenging. I am happy that finally I could document all these to the best of my ability before these voices turned into whispers,” Anvita told The Federal.

The Andaman Islands are separated from the Malay Peninsula by the Andaman Sea, an extension of the Bay of Bengal, and are part of the Union Territory of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands belonging to India. The capital city of the Andaman Islands is Port Blair, situated in the south of the Islands, 1,255 km from Kolkata and 1,190 km from Chennai.

There are 10 languages in the Great Andamanese family, which can be grouped into three varieties: southern, central and northern. These are: Aka-Bea, Aka-Bale, the southern variety; Aka-Pucikwar (known as Pujjukar in the currently spoken language), Aka-Kol, Aka-Kede, Aka-Jowoi, as the central variety; and Aka-Jeru, Aka-Bo, Aka-Kora (known as Khora by the present speakers) and Aka-Cari (known as Sare by the present speakers) a northern variety. Except for Jeru, all Great Andamanese languages are now extinct, according to Anvita. She said the present-day Great Andamanese language is a mixture of four northern varieties, with sporadic interferences from the central variety such as Aka Pucikwar.

There were several reasons that drew Anvita towards working on Great Andamanese. The topography of the area, its people, and their antiquity and above all scant availability of published material on their language coupled with the fact that her observation in 2003 after conducting a pilot survey of the languages of the Great Andaman that this language seems to be a class apart from the other two languages of the region – Onge and Jarawa.

“Unlike Jarawa and Onge, Great Andamanese is a moribund language. I was encouraged by my linguist friends to study and document the language widely to unearth a vast knowledge base buried in the linguistic structures of Great Andamanese before it is lost to the world. Not only my results of 2003 were later corroborated by geneticists in 2005 it gave me assurance and proof beyond doubt that this group of languages forms the sixth language family of India,” she said.

The history of the present Great Andamanese, according to Anvita, is a tale of many tales. “Outsider-contact has brought diseases, subjugation, sexual assault, and ultimately decimation of the tribal culture, tribal life, and tribal language. For years, the Jarawas maintained the same isolation and now they regret the interaction with us. Most of the Great Andamanese people have forgotten their heritage language and speak only Andamanese Hindi. Some of them have a passive knowledge of Bangla (Bengali),” said Anvita, who won the Padma Shri, the fourth highest civilian award of India and the Kenneth Hale award from the Linguistic Society of America for her work.

When Anvita reached the island, there were 10 speakers but now only three remain who can speak present-day Great Andamanese but prefer not to. “Colonisation by the mainland Indians exposed the tribe to babu Hindi as well as to the lingua franca Andamanese Hindi existing in the Island. As of today, a few of them are hired by the government in Port Blair and some children go to the local schools so that exposure to local Hindi is intensive. The elders lament that they did not teach their heritage language to the youth. Boa Sr, the last speaker of the Great Andamanese language would say, ‘Everything is gone, our land, our forest, our water, our language, nothing is left,’” she added.

It had always been a mystery whether the Andamanese community practised cannibalism. “There is and was a total denial about this fact by the community members. However, a couple of folk tales collected during the project reveal that cannibalism was practised by some. There are enough references of head-hunters. They are mentioned as if the tendency resided with supernatural beings that were not part of the common society,” said Anvita.

If you want to study the language of a people, you need to first understand the history of the people who mainly speak it. The knowledge of the people on the island was remarkable. “These tribes are neither poor, nor uneducated. Their knowledge of the environment comprising birds, fishes, medicinal plants and their uses, sea life, weather predictions, and the earth they walk on is amazing. They are neither cowardly nor violent. They safeguard their folks both women and children from outside intervention. They have known the wonders of isolation and that is what they want to maintain. However, we have lost Great Andamanese as the process of mainstreaming them started with colonisation first by Britishers and later by Indians,” she added.

The danger of colonisation haunts the island people even today. “They are nowhere now– neither connected to their roots nor connected to the world that the government offers. Cultural amnesia and loss of their heritage language has affected their cognitive and perceptive powers adversely. The modern generation neither feels connected to forest and sea-life nor to city-life. It’s a lost civilization bewildered by their present. In this scenario, the stories and songs of my recent book may serve as the only priceless heritage of the ancient civilization of India,” said Anvita, who taught linguistics at Jawaharlal Nehru University for four decades. She is now an Adjunct Professor of linguistics at Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, Canada.

Anvita’s unending passion for the language and culture of the people in the Andaman Islands eventually led her to document many dying languages there. How does documentation help? “Since language codes our perception, worldview, history, indigenous knowledge about ecology, history of migration and secrets of human survival, it is of utmost importance that we retain and know about the languages of the tribes,” she said. “As of today, we have more than 800 languages in the country which are spoken and not written down, engulfing a vast amount of secrets of human nature, human tolerance for others and survival. Orality results in cumulative expansion of knowledge. Intergenerational transmission of this knowledge is done through language. If this transmission fails as is happening today language documentation becomes mandatory.”

For instance, Anvita tried to document Great Andamanese as best as possible before it turned into oblivion. The Great Andamanese people were hunters and gatherers till the end of the 19th century, their knowledge about the environment is locked in their language which has been extensively documented in the trilingual interactive dictionary (Dictionary of the Great Andamanese Language) and later in a book on birds titled Birds of the Great Andamanese that she brought out in 2011. More than 97 names for different birds, 157 names for varieties of fish, about 300 names of flora including many medicinal plants, six different names of seashores depending upon their distance and nature, 18 different names of smells and odours – all indicate that any disturbance to the environment leads to damage to the indigenous culture and language.

“The language is depleted of this vast information when jungles are uprooted, or tribes are dislocated as words lose context and information. When the tsunami came on December 26, 2004, tribes of the Andaman, Jarawa, Onge and Great Andamanese saved themselves as their knowledge about tsunami was intact in their language. They immediately interpreted the patterns of waves and sea churning and running to a safe place,” said Anvita.

Nao Jr was the eldest male member of the tribe and the true heir to his brother the former king, Jirake. “Nao Jr knew three of the four languages which have come together to form what we call today the Present Great Andamanese (PGA). With the help of Nao, we produced the very first “Book of Letters” and in this way we gave a script to the language. The specimen of the script can be viewed on any page of the dictionary which is in trilingual mode,” said Anvita, who launched her website (www.andamanese.org) recently.

Since Great Andamanese is a moribund language of the only surviving pre-Neolithic tribe, the remnants of the first migration out of Africa 70,000 years ago, she said she was driven to launch a website introducing readers and users to the world of ancient knowledge, beliefs, values and of course the heritage language.

“My work does not limit to Great Andamanese alone as I have researched on the languages of Onge and Jarawa, as well as two of the endangered languages of the Nicobar Islands such as Luro and Sanenyo, I thought of a comprehensive website of Andaman and Nicobar Islands and that is what this site is about. It is an interactive website as one surfs one finds oneself in the ancient world of sounds, songs, conversations, narrations, and the beauty about the uniqueness of the language of the Great Andamanese people. It is full of images and videos of songs sung by Boa Sr the last keeper of heritage language of the world Bo from the Great Andamanese people. Videos of Jarawa and Onge are also included,” said Anvita.

For Anvita, the journey with the languages never ends. She is working on documentation of Luro and Sanenyo, the two languages of the Nicobar Islands. “The interactive dictionaries of these two languages are already uploaded on the website of the Central Institute of Indian Languages, Mysore. The work on their grammar is on,” she said.