- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

A Ladakhi royal family fighting Chinese land grab since 1980s

The erstwhile royal Dorje family has lost their ancestral property, a heritage castle in Chabji to the Chinese while another one in Chumur area has been made out of bounds as it falls in the border buffer zone.

For over three decades now, an erstwhile royal family from eastern Ladakh’s Chabji-Chumur area has been putting up a solitary fight to retrieve their land from Chinese domination. They have repeatedly requisitioned power corridors in Srinagar and New Delhi for an intervention. The family’s pleas went unheeded all these years until a fresh wave of border clashes broke out between Indian...

For over three decades now, an erstwhile royal family from eastern Ladakh’s Chabji-Chumur area has been putting up a solitary fight to retrieve their land from Chinese domination.

They have repeatedly requisitioned power corridors in Srinagar and New Delhi for an intervention. The family’s pleas went unheeded all these years until a fresh wave of border clashes broke out between Indian and Chinese troops in this mountainous cold desert.

The two-acre piece of land (16 kanals and 5 marlas), located near the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in Chabji-Chumur area of Ladakh, has been occupied by the Chinese since 1984.

The land that once housed a heritage castle was the ancestral property of Rongdol Dorje and his brother Tsering Dorje.

“I cannot forget my childhood days spent in that 150-year-old palace built on our ancestral land named after our forefather Kunzang Dorje,” Dorje Dawa, the 60-year-old son of Rongdol Dorje, tells The Federal in an exclusive chat. “The Chinese have ruined the castle by raising their own ugly structures on it.”

During their monarchical reign in Ladakh, Dawa says, his ancestors were known as the ‘Rupsho Rajas’, after the Rupsho Valley.

“We had a 300-year-old palace at Chumur and a 150-year-old castle at Chabji.”

During summers, the family used to stay in Chumur and would shift to Chabji in winters. Their summer and winter homes were 20 km apart. Today, the royal family’s summer palace at Chumur has become a buffer zone with the Indian armed forces making it out of bounds for the family and civilians due to security reasons. The low-lying and relatively warmer Chabji winter home—a fertile area for cultivation—is now under Chinese domination and remains elusive to the family.

Before the 1980s, the Dorjes and many nomads from Rupsho valley used the land for winter grazing and cultivation of barley and peas, and grass for cattle, Dawa says.

Sometime in 1985, a teenage land tiller who was looking to grow barley was pushed back by the Chinese troops.

“It had never happened before,” Tshering Tobgail, now 52, tells The Federal. “They never vacated the fields after that.”

“We were literally thrown out of our lands,” says Dawa.

Since then, Dawa and his uncle Tsering Dorje, the struggle-hardened campaigners, have been awaiting the “much-needed” intervention from New Delhi to restore their rights on the ancestral land.

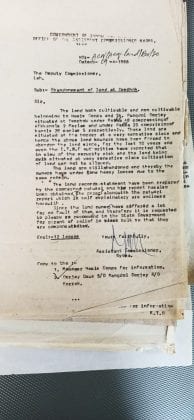

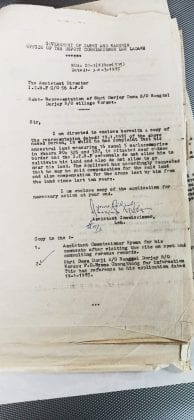

With original revenue documents showing Rangdol Dorje and Tsering Dorje as owners and signed by the revenue officer (patwari) of Kurzok Halwa in Nyoma tehsil of Leh district, they ran from pillar to post requesting intervention.

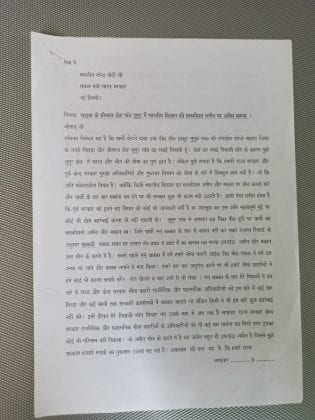

“We even ran a multi-front movement against the Chinese occupation by raising the matter from the district administration to the chief minister of the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir to the Prime Minister of India, but to no avail,” Dawa says.

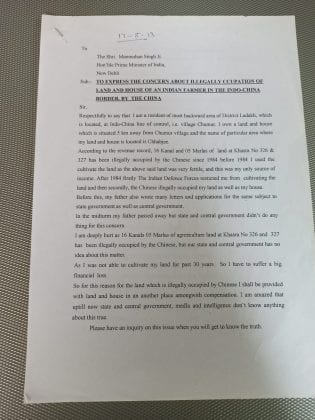

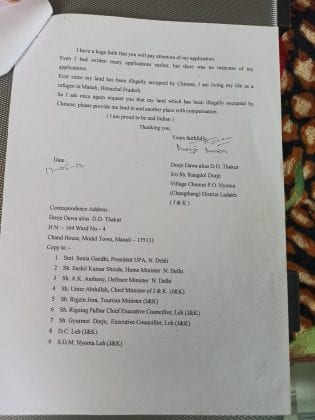

In 2013, he had written to then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, requesting intervention to retrieve his land occupied by the Chinese. A copy of the letter was marked to UPA chief Sonia Gandhi, then home minister Sushil Kumar Shinde, then defence minister AK Anthony, then chief minister of Jammu and Kashmir Omar Abdullah and other ministers and officials concerned.

After Narendra Modi took over, Dawa had written to the current Prime Minister too, accusing the state government and previous central government of being clueless about the border issue.

‘No one entered India’

After the two most-populous countries began locking horns at the Line of Actual Control (LAC), the Dorje family raised the matter again.

While defence analysts assert that Chinese troops intruded into the Indian side along the LAC in eastern Ladakh, PM Modi recently said that “no one entered India”.

New Delhi maintained that China was given a befitting response at the LAC.

But Ladakh natives, aware of the ground situation and monitoring the confrontation site, paint a contrasting picture.

“China is acting shrewd at the LAC,” says Gyurmet Dorjey, Congress Councillor from Ladakh. “They thrash our nomads for grazing their Pashmina goats and other livestock in the winter pasturelands at Korzok, Chumur and Tegzzong areas falling near the LAC.”

Around one lakh Pashmina goats are dependent on this winter grazing land, Dorjey adds, but China’s PLA is hampering their age-old practice with their incursions on Indian side.

He says that the natives have been raising the issue for many years now.

In 2015, when the then-Home Minister Rajnath Singh visited Ladakh, he was also supposed to visit Chumur. “We had prepared the representation,” Dorjey says. “But Singh went back from Demchok itself.”

In the same year, a letter from the local representatives of Leh Autonomous Hill Development Council (LAHDC), a copy of which is with The Federal, highlighted the Chinese incursion on the land of the two Dorje brothers in Ladakh.

Despite raising the issue, the matter has remained untouched in the five years since.

Silent land grab

“The only reason China is so adamant to occupy pasture lands along the LAC in Changthang is to prevent nomads from their traditional grazing and get hold of this strategic mountainous region,” Dawa says, blaming government agencies for “misreporting” China’s LAC incursions to Central ministries all these years.

“Due to the negligence of the agencies, I lost my 16 kanal and 5 marlas of land while the government lost their 65 sqkm land in the same area of Chabji to China over the years. The silent land grab technique by China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) is gradually shrinking India’s Ladakh.”

The unabated Chinese incursions have altered the ground reality and life in eastern Ladakh. Dawa says that during his childhood, around 55 nomadic families used to live in Chumur itself. “But due to fear of the Chinese now,” he says, “they have reduced to only 11. Rest of them have left the area long back.”

According to him, not only have the borderlines between China and India changed in eastern Ladakh, but it has also affected the nomads associated with the famous Pashmina industry of the world.

“These nomads of Changthang are innocent,” Dawa says. “The government has largely ignored their plight, even when they lost their only livelihood, their winter pasture lands, to repeated Chinese incursions over the years.”

Even today, Dawa says, not many know how, 280 km from Leh city, China is eating away at Indian borders. He also blamed the “biased media” coverage for that.

“Ask me, as a native, I will tell you what the border people are going through right now. They can’t even raise their voice against the wanton land loot of their homes and pastures. Has anyone ever seen these nomads protesting against the government?”

Demchok property with armed forces

As the “only person in Ladakh” who owns a 300-year-old ancestral property in the cold desert, Dawa says his family had to give away another heritage property in Demchok, close to the LAC on the eastern extreme of Ladakh, for a paramilitary barrack to come up there after 1947.

“Before 1947, our home in Demchok would shelter two Lamas,” he says. “The house and land was then given to the Indian troops to set up their office and tents to keep an eye on the enemy.”

In the 1962 war, when the Indian side suffered casualties, Dorje’s house was badly hit. “But again in 1965, the Indian army and government agencies set up their makeshift arrangements there which still exists,” he says.

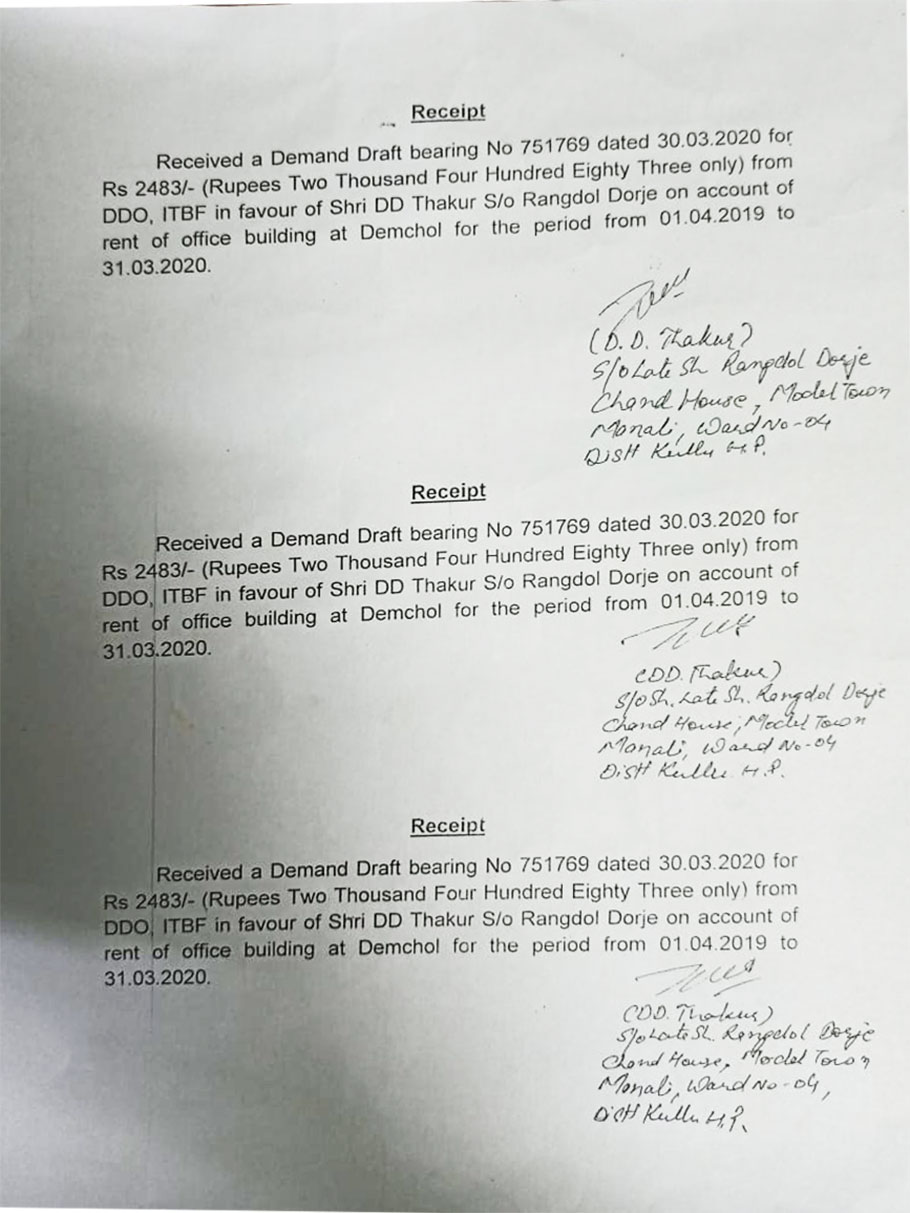

“My family is being paid ₹200 monthly rent for the strategic site,” he says, showing receipts amounting to ₹2,483 given by the Indo Tibetan Border Police (ITBP) as the annual rent for the property.

While the local administration has pleaded his case for appropriate compensation, Dawa wants New Delhi to fight China in the international court to keep it away from Ladakh.

“We don’t merely fight for our ancestral land, we fight for India’s land under Chinese occupation,” says Dawa. “My land is proof that the area belongs to India.”