- Home

- News

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- World Cup 2023

- Features

- Health

- Budget 2024-25

- Business

- Series

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Premium

- Science

- Brand studio

- Home

- NewsNews

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Sports

- Loading...

Sports - Features

- Budget 2024-25

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium

5 yrs on, what demonetisation doesn’t let the common man forget

On the evening of November 8, 2016, Dheeraj Rai’s shop in Gandhi Nagar market, Delhi’s largest textile bazaar, was teeming with shoppers fetishizing over the right fit and colour of jeans that Rai and his team of tailors had been sewing for years. That was the last time he remembers seeing such a footfall on his shop floor. “As soon as news spread about pradhan...

On the evening of November 8, 2016, Dheeraj Rai’s shop in Gandhi Nagar market, Delhi’s largest textile bazaar, was teeming with shoppers fetishizing over the right fit and colour of jeans that Rai and his team of tailors had been sewing for years. That was the last time he remembers seeing such a footfall on his shop floor.

“As soon as news spread about pradhan mantriji’s notebandi [Prime Minister’s note ban] announcement, there was chaos everywhere. Things started to fall apart soon after,” says Rai. The days and months that followed brought more chaos and fewer and fewer customers to his shop. “I had to let go of my assistants one by one, I couldn’t afford to pay them anymore. Soon, I was neck-deep in debt.”

It took Rai three years to wobble back on his feet, only to crash-land a few months later due to the pandemic. “Now, I have become a complete kangaal (pauper). My panauti (misfortune) that began with notebandi just refuses to go away.”

While Rai still curses that evening of 2016, there are millions of others who have similar tales of an unending nightmare — some more devastating — that continue to haunt them even five years after the old currency notes of Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 were rendered void.

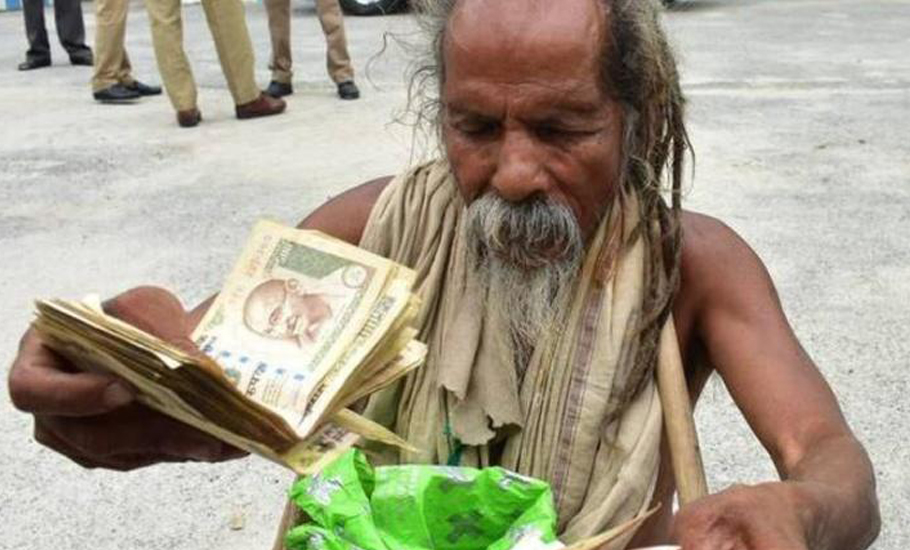

In Tamil Nadu’s Krishnagiri district, a visually impaired man in his 70s got to know about demonetisation from a cobbler only on October 17 this year and realised that all his savings — Rs 65,000 — were in the old currency notes.

Chinnakannu had saved that money ‘earned’ seeking alms on the streets of Chinnagoundanur village in Krishnagiri. He was then directed to the Collectorate office by some good Samaritans for help. While Chinnakannu’s story went viral following media reports, the administration forwarded the petition to the RBI. Amid all this, a Chennai resident offered to compensate him for the loss.

But not everyone is as lucky. Just four days after demonetisation, a newborn baby died in Mumbai after being denied treatment by a hospital as the parents could not pay the necessary deposit in notes less than Rs 500 denomination.

Jagdeesh and Kiran Sharma’s three-day infant was one among more than 100 people whose deaths have had strong links with the suddenly executed move. Several of them who died awaiting their turn to withdraw money suffered from heart ailments, hypertension, diabetes and other ailments. But their families believe it was the sheer impact of the move that added to the stress and ruined families forever.

Experts believe the after effects continue even now. In 2018 , two years after demonetisation and a year after the implementation of the GST — another hurriedly implemented move that saw major chaos — businesspersons’ suicide rose by three per cent. In the following year, businessperson suicides grew by 13 per cent. This likely worsened during the pandemic.

Among the non-fatal long-term implications, growing unemployment and increase in inequalities leading to a decline in demand have been too palpable to ignore. The result has been an economic slowdown even before the Covid-19 pandemic hit in 2020.

According to Prof Abhijit Sen, economist and former member of Planning Commission of India, demonetisation has had very little long-term positive impact. “In the short term, alternatives to cash emerged. But that transition would have happened even without demonetisation. In actual terms, demonetisation led to falling back on real income as it put the economy in doldrums with people losing jobs, industrial output getting affected with a sudden cashless economy.”

For the common man, the losses continue to grow every year even as economists debate if the masterstroke to curb black money was a success or a disaster.

The big announcement

At 8:15 pm on November 8, 2016, PM Narendra Modi appeared in a televised speech, announcing the scrapping of two of the highest-valued notes back then — Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 — that accounted for 86 per cent of all currency notes in circulation in value. The note ban came into effect as of midnight on that day.

The prime minister listed out three reasons behind the move a) rooting out black money, b) eliminating counterfeit currency and c) ending the financing of terrorism. Soon, many in the government, including his then defence minister the late Manohar Parrikar, called it a “surgical strike” and “masterstroke”.

In the ensuing melee, the prime minister announced that he was willing to take any punishment if Indians decided that they had suffered without any cause.

Many among the common man, and not just intellectuals, too felt the goals were laudable. So, the move was inevitable. But soon, most of these people started to doubt their own optimism.

Within days, in what could perhaps be termed as admission of mistake, the government changed the goalpost. It soon announced that the move was aimed at making the economy “cashless”. When leading economists started making noise and saying that the cashless dream would take a long, long time to realise, the government pared down the goal to a “less cash economy”.

To add insult to government’s injury, as much as 99.3 per cent of the demonetised Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes returned to the banking system by August 2018, indicating that just a miniscule percentage of currency was left out of the system after the note ban aimed at curbing black money and corruption.

While there was no impact on black money or black-income generation, the goal to suck dry terror funding also seemed far from achievable, as per government’s own statistics just a year later. Cross-border terrorism in J&K, in fact, went up between November 1, 2016 and October 31, 2017. There were 341 terror incidents during this period compared with 311 a year ago in the same time span. While the total number of such incidents recorded were 2,140 in 2018, the figure stood at 3,479 in 2019 and 5,133 in 2020, according to the Ministry of Home Affairs. However, the government says it saw a sharp decline in 2021 with only 664 instances of ceasefire violations reported till June. Could this be an impact of the demonetisation five years later? Seemingly unlikely.

When it comes to digital payment, in other words a cashless economy, it did spike immediately after demonetisation. But by May 2018, “the cash-to-GDP ratio was already back to pre-demonetisation levels, according to this March 2019 study.

A survey of more than 1,000 small-scale merchants concluded that less preference for digital payments in India is not due to inadequate availability of options but because of low demand. The reasons behind this low demand include “a perceived lack [of] customers wanting to pay digitally and concerns that records of mobile payments might increase tax liability”.

There are other concerns as well. After demonetisation, 38-year-old Mallika from Guwahati upped her usage of mobile wallets and debit cards. “I started using UPI to pay my bills and buy groceries and even for cab rides,” she says. However, soon Mallika realised that she was spending more. “Earlier, if I wanted to get vegetables for Rs 100, I was paying cash and spending only that much on that particular occasion. Now, I have to buy a minimum amount. The online delivery provider won’t deliver unless it matches their minimum purchase level. Neither would the shopkeeper swipe the card.”

“Also, I feel I’m more susceptible to phishing and online fraud,” says the mother of two.

There was again a rise in digital payments in 2019-20. In fact, a massive one. According to data by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), India recorded 3,412 crore digital payment transactions in 2019-20 from 2,326 crore the year before and more than six times the level five years before. In other words, during these five years, that is, between 2015-16 and 2019-20, digital payments saw an annual growth rate of 55.1 per cent in terms of transaction volumes. In 2020-21, the number of digital transactions rose even further to 4,371 crore.

So is true for cash flow, albeit at a slower pace. Five years after the demonetisation, currency notes in circulation went up in the last financial year as many people opted to hold cash as a precaution amid the COVID-19 pandemic disrupting normal lives and economic activities. The trend likely continued this year, too, as a devastating second wave of the pandemic during April-May forced people to pay cash for everything from medicines to oxygen cylinders on the black market.

The same reason — pandemic — is attributed to the rise in digital payment as well. The RBI in its Annual Report 2020-21 noted that the Covid-19 pandemic fuelled the proliferation of digital modes of payments.

While many like Mallika preferred or were forced to stick to digital for no-contact delivery of essential items due to the fear of contracting the Coronavirus, it wasn’t an option for many men and women — farmers, labourers, elderly, digitally unlettered — who generally don’t come to mind at once when talking of a cashless economy.

Sachin Meega, a farmer leader and president of Karnataka Kisan Congress, says other than commercial crop farmers, the rest are still struggling as an aftereffect of demonetisation. “When the note ban was announced, it crippled the rural economy with lesser cash and farmers couldn’t buy seeds and fertilisers. To save the crops, many took loans from money lenders at higher rates of interest, which they are still paying back,” he says. Even the dairy sector is in a difficult state.

“Before demonetisation, the cost of feed was Rs 600 per 50kg bag. Today, it has increased to Rs 1,300. So where’s the real benefit? It only increased the input costs. Farmers are still getting Rs 26 per litre of milk as it was in 2016.”

Black money, he says, is not in farmers’ pockets. “They are still struggling for survival.”