In times of NRC, CAA, ‘CPM’ clings on to new name, not namesake for safety

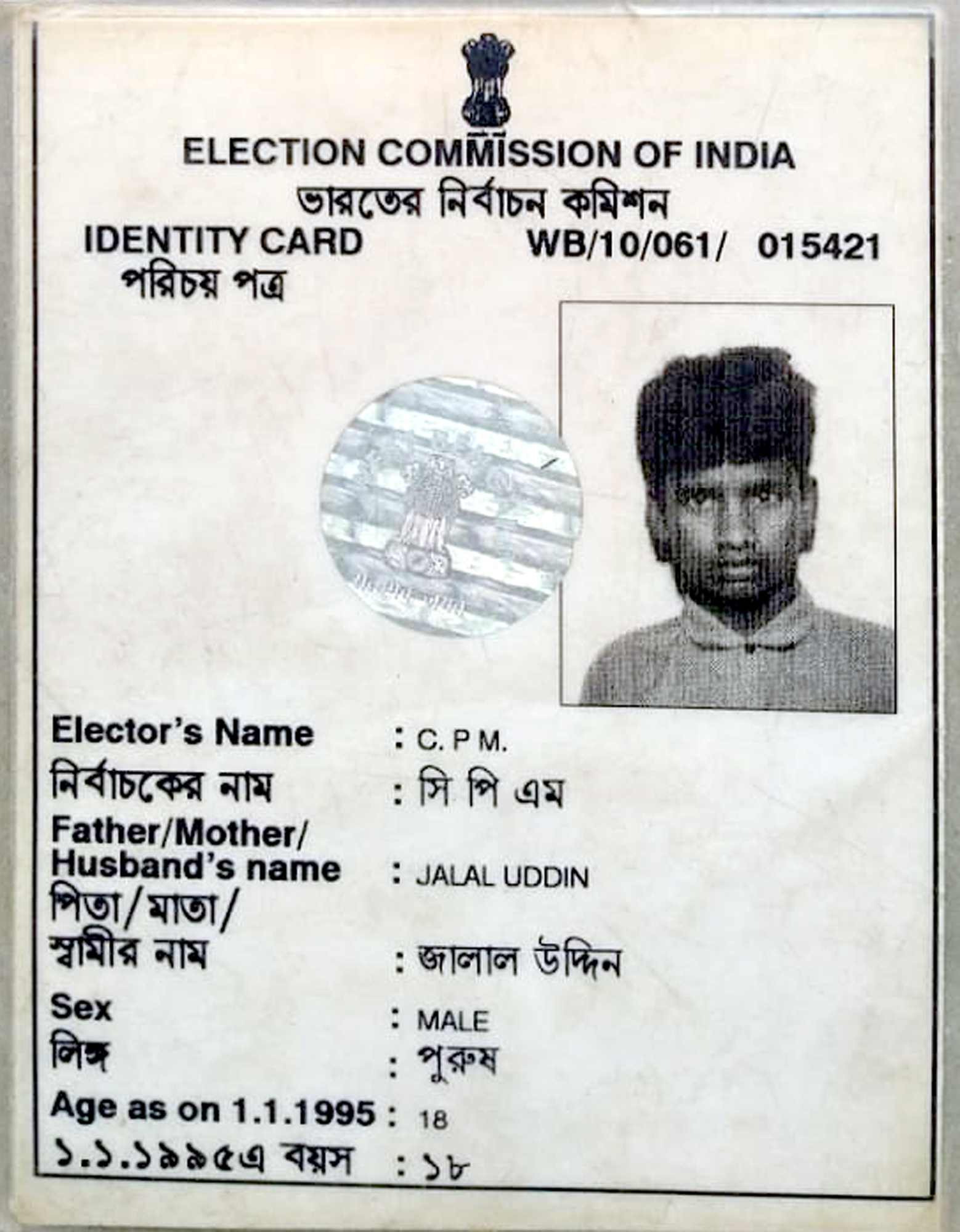

Ever heard of someone named after a political party? In June 1997, a baby boy born in a poor peasant family in Murshidabad district was named ‘CPM’, after the Communist Party of India (Marxist), barely 10 months after the first Left Front government came to power in West Bengal.

Forty two years after his birth, as the CPI (M) fights an existential battle in the state, CPM found his name inappropriate in the current political matrix dominated by controversial citizenship issues like the National Register of Citizens (NRC).

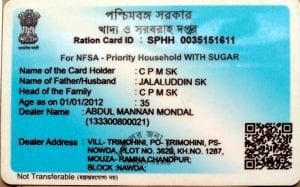

With BJP leaders continuing to stoke the fear of NRC in the state ahead of the 2021 Assembly elections, CPM recently, through an affidavit, changed his name to Ehannabi Sheikh to make it sound more compatible with names of other members of his family.

During the recent updation of the state electoral roll, he got his new name registered in the voters’ list, not willing to take any chance with any future citizenship enumerator.

“I have checked online that my new name has been updated in the voter list. Once I get the voter identity card issued in my new name, I will take steps to rectify my name in other documents such as Aadhaar and ration cards,” Ehannabi told The Federal.

Ehannabi’s move for an identity change only goes on to show that Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee’s attempt to allay the NRC fear stating the exercise would not be allowed in the state, is yet to convince many.

“I am a poor farmer, so I don’t understand these complicated issues much. But people here say possibilities of an NRC in Bengal cannot be ruled out, after all it has been done in neighbouring Assam,” he said.

After the NRC was rolled out in Assam, and the BJP leaders announced the introduction of a similar exercise across the country, his father Jalaluddin in particular had been insisting that CPM rechristen himself in sync with names of others in the family.

The name change, however, did not flicker his loyalty for the party, which had been his identity for over four decades. He firmly said “no” on being asked whether he would change his political affiliation too.

After all, Ehannabi pointed out, he did not change his name even when the political landscape in Bengal underwent a change in 2011 with Trinamool Congress dethroning the CPI (M)-led government.

He was born in April 1978. The CPI (M) was then at the zenith of its popularity, particularly in rural Bengal. Within months of taking charge, the Jyoti Basu government took several initiatives for land reform and decentralisation of power, making it the darling of rural masses, which helped it to go on to rule the state uninterrupted for 34 years since then.

Ehannabi’s birth coincided with the preparations for the panchayat elections held in June 1978 in which Left Front won a landslide victory, making West Bengal the first state in the country to successfully implement the panchayati raj system.

One of Ehannabi’s uncles, Anwarul Haque was put up as a candidate by the CPI (M) in the rural body elections. It was during the campaign that everyone started to call the newborn child “CPM” lovingly. After Haque won the gram panchayat elections, the baby was officially christened ‘CPM’, amidst the jubilation of the electoral victory.

That was a different era, when a name perhaps was not as significant as today.

In today’s NRC-CAA driven political fabric of Bengal, Ehannabi feels even a name could decide whether one stays in a detention camp or at home with the family.