Bengal village with Naxal past embodies failure of Modi’s ‘adarsh gram’

If any one village sums up the failure of the Centre’s Sansad Adarsh Gram Yojana (SAGY), it is Sebdella, long known for its association with the Naxal movement.

If any one village sums up the failure of the Centre’s Sansad Adarsh Gram Yojana (SAGY), it is Sebdella, long known for its association with the Naxal movement.

The scheme’s failure is now well documented by a government’s own assessment study. Seven years ago on a cold winter day, the scenario was different.

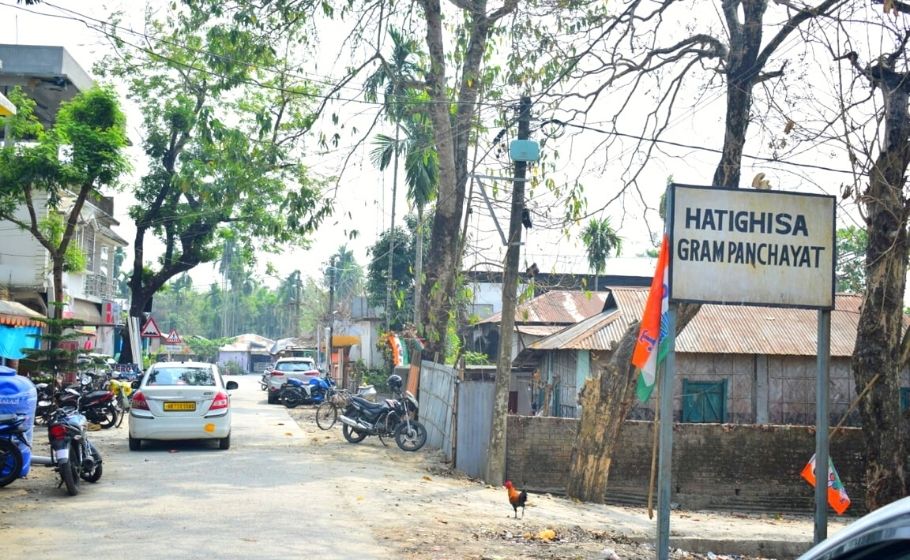

Sebdella was stirred up in anticipation of a change that eluded the village for decades, even after a hard-fought armed rebellion. The sleepy village in West Bengal’s Darjeeling district is part of a 30-village cluster under Hatighisa panchayat adopted by then Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) parliamentarian from the area S S Ahluwalia to develop its as a model village.

On that day in November 2014 Ahluwalia visited Sebdella to announce the launch of his ambitious plan under the SAGY, one of the earliest flagship schemes of the Narendra Modi regime.

The scheme, launched by Modi in October 11, 2014, envisages developing physical and institutional infrastructure of the adopted villages to make them stand out as an ‘adarsh’ — a role model. At the launch of the scheme, the BJP MP promised to usher in holistic development and make the Hatigisha village panchayat self-reliant.

The selection of the panchayat for Modi’s pet scheme was loaded with political symbolism. One of the villages under the panchayat is Sebdella where a founding leader of the Naxalite movement of the 1960s, Kanu Sanyal, spent most part of his life and eventually committed suicide in the village in 2010. The Naxal leader’s tin-roofed modest house has been converted to Kanu Sanyal Memorial Trust Bhawan after his death.

Hatigisha was the hotbed of the peasant uprising that swept Bengal in the late ’60s and early ’70s. The panchayat is the part of Naxalbari development block. Naxalbari, now a hardscrabble town, was the cradle of the armed rebellion came to be known as the Naxal movement.

“Ahluwalia had once come here, promising to make the area a model village. I was also called in the meeting. There the BJP MP told me that he would fulfill the dream of Kanu-da in his own way. I told him it’s good if you can achieve it….. We all will support you,” said Shanti Munda, a close aide of Sanyal.

Septuagenarian Munda, who lives in Sebdella, said that was the last time she saw Ahluwalia in the area. As for the promised model village, she said it became another pipe dream.

The model of development can be gauged from the crippling shortage of water the villagers grapple every day. There are only two deep tubewells to cater to the water need of around 250 houses in Sebdella, having a population of 1276 people. The tubewells remain dry most part of the year.

“The only source of some water in the village is taps installed by the panhayat in four places. Twice in a day for a few hours we get water from the taps. To collect water there is always a long queue,” said Sebdella resident Sushma Munda, who is studying Arts in Nakshalbari (Naxalbari is also spelled as Nakshalbari) College, some 10 kms away. The college was established in 2008.

The tar road that leads to the village from the highway has been crumbled into a dirt track in many places due to lack of maintenance. Link roads within the village are mostly mud pathways. That the village is desperately poor is evident from mud hutments that dotted it.

The situation is no different in Nandalal, Giramuni, Damdama and other adjoining villages under Hatigisha panchayat. A brief visit to the place gives an impression if anything, this panchayat adopted by the BJP MP, is a model of underdevelopment.

A former pradhan of the Hatighisa panchayat, Jyostho Mohan Roy said apart from building a culvert behind the Hatigisha High School at a cost of Rs 25 lakh, Ahluwalia did nothing towards making the village ‘adarsh.’

“Except for the road leading from the highway to Sebdella and other adjoining villages, no road is tarred. There is also an acute shortage of potable water,” said local farmer Prasanjit Mallik.

Related news: In poll season, Mamata adds ‘Maa’ to birth-to-death welfare schemes

Admitting that Ahluwalia failed to implement the SAGY, the BJP’s national council member Ganesh Chandra Debnath blamed the state’s Trinamool Congress government for the failure. “The state government was totally non-cooperative. In every step it created hurdles for implementation of any development project, be it in providing piped drinking water or construction of a public toilet. As a result, Hatigisha was deprived of the benefit of another development scheme of the Modi government,” says Debnath, who was deputed by Ahluwalia to oversee implementation of the scheme.

Hatighisa, however, is not an isolated case of failure of the scheme as the recent study of the government points out. The study commissioned by the Rural Development Ministry found out in August last year that the scheme failed to make any “significant impact.”

“In isolated cases, where MPs have been proactive, some infrastructure development has taken place, but the scheme has not made any perceptible impact,” the study said.

The study was conducted by a 31-member common review mission (CRM) team led by former bureaucrat Rajeev Kapoor.

For the failure of the scheme the CRM blamed its current format. “Our experience in the field makes us presume that because of non-allocation of funds for the SAGY programme, there is a tendency of omission about the programme,” the CRM said.

That the scheme is getting a quiet burial is evident from the lack of interest parliamentarians are showing in adopting villages.

In the first phase (2014-16) of the scheme, 703 villages were adopted. In the second phase (2016-19) the number came down to 500. It then dwindled to 290 in the third phase (2016-19). In the fourth phase (2019-20) the number had slightly increased to 359, only to nosedive to just 24 in the fifth phase (2020-21). In the adopted villages most of the projects planned were not completed, the study showed.

Related news: WB govt carrying on social welfare schemes despite tight fiscal condition : Mamata