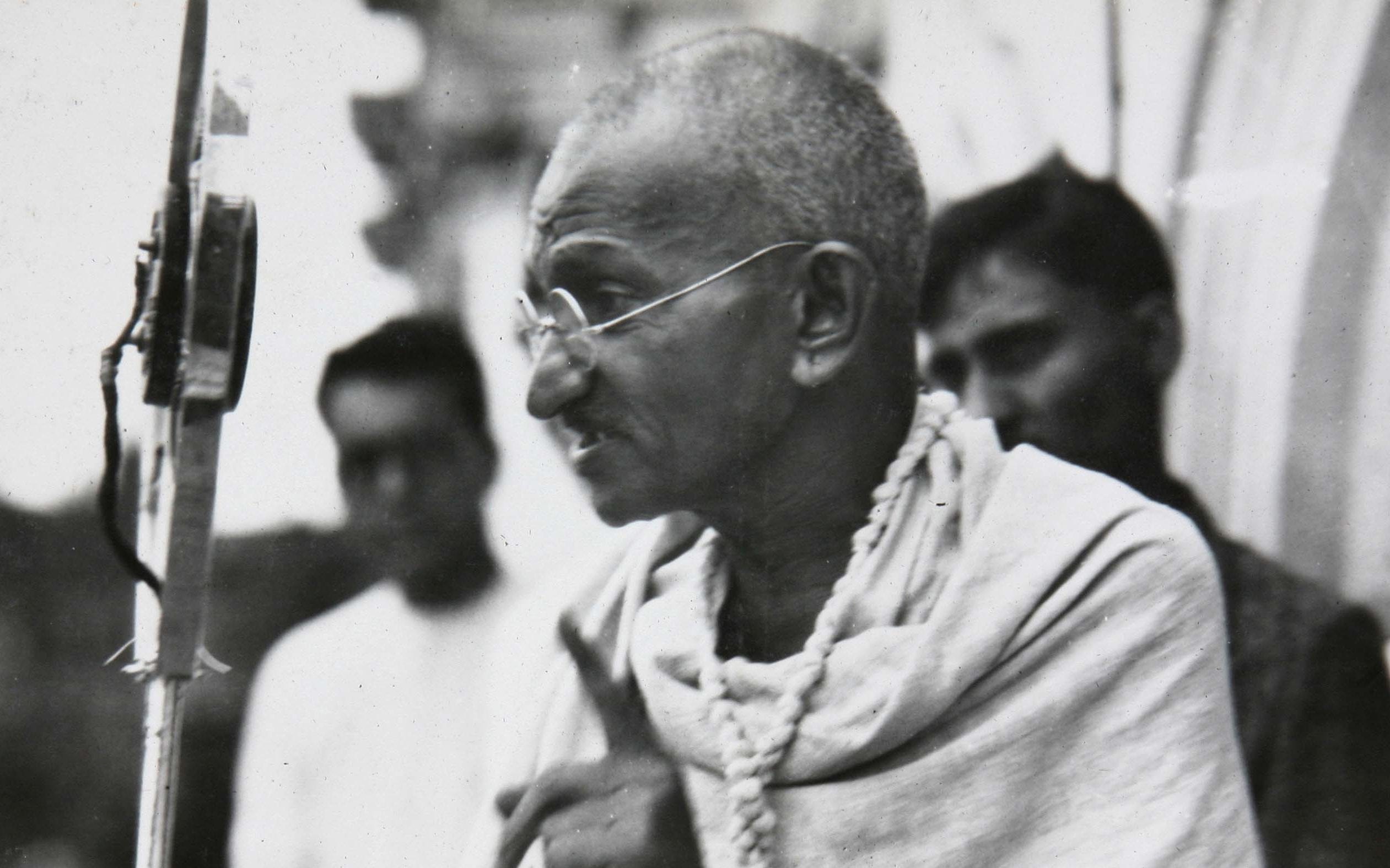

What Mahatma Gandhi said on Aurangzeb, and how it matters now

The Mahatma's many references to Aurangzeb to promote spinning stand in sharp contrast to the manner in which the Mughal emperor is now dragged into communal politics

Present leaders with a mandate to rule India are repeatedly referring to the “persistent mindset” of Indians shaped by, what they call, baarah sau saal ki ghulami (1,200 years of slavery). This manufactured narrative includes, apart from almost 300 years of British rule, the entire period of Mughal rule in large parts of India.

This description of the Mughal period as a period of slavery has the subtext of targeting Mughal rulers as invaders and treating Muslims living in India with a highly prejudiced perspective filled with sustained hate and hostility towards them.

Also read: It’s time India chased glory, not past sins

Now, apart from targeting Muslims and their places of worship, disparaging remarks on Islam itself and its revered Prophet have been made by two BJP spokespersons. The two were removed from their party following backlash from several Gulf countries. Indonesia and the Maldives, too, reacted very sharply to express their hurt feelings.

Mughal period not one of slavery

The twisted understanding and interpretation of history in terms of 1,200 years of slavery is done in a calculated manner — in complete contrast to facts of history — to spin polarised narratives and deepen and sustain divisiveness for treating Muslims in an unfair manner.

This sinister strategy should be seen in the backdrop of the Mandir-Masjid agenda, which, of late, has gained huge traction because of the orders of a court in UP to do a survey in Varanasi’s Gyanvapi Mosque.

Also read: Hindutva politics of hate, manipulation of history now India’s cross to bear

The whole idea of repeatedly invoking the 1.200-year narrative is aimed at recurrently stoking communal hysteria for projecting Hindus as victims of the Mughal rule. The fight among rulers of that period is falsely projected in terms of the clash of faiths they represented.

For instance, the fight involving Shivaji and Aurangzeb on one hand, and Rana Pratap and Akbar on the other, is projected as a fight among Hindu and Muslim rulers. It flows from the concoction of history to reaffirm the convoluted version that India suffered baarah sau saal ki ghulami. This is being done in negation of the vision of India articulated during the freedom struggle, especially by Mahatma Gandhi, the Father of our Nation.

Gandhiji, instead of describing the Mughal rule as a period of slavery, saw in it some aspects of swaraj which enabled Shivaji and Rana Pratap to take on Aurangzeb and Akbar, respectively. He said that with the advent of British rule in India, this swaraj prevailing in the pre-British period was lost.

Also read: Bulldozer politics dents the rule of law

It is worthwhile to quote the Mahatma’s exact words. Addressing a huge gathering on March 24, 1921, in Cuttack, he famously said, “The pre-British period was not a period of slavery. We had some sort of swaraj under Mughal rule. In Akbar’s time, the birth of a Pratap was possible, and in Aurangzeb’s time a Shivaji could flourish. Have 150 years of British rule produced any Pratap and Shivaji?”

The Mahatma on Aurangzeb

It is instructive that during the freedom struggle Gandhiji invoked the name of Aurangzeb on multiple occasions when he spearheaded a nationwide campaign for making spinning and the usage of khadi a mass movement.

In his article ‘Music of the Spinning Wheel’, published in Young India on July 21, 1920, Gandhiji observed: “Slowly but surely the music of perhaps the most ancient machine of India is once more permeating society.” He then referred to Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya’s statement that ‘as long as the ranis and maharanis and the ranas and the maharanas of India did not spin yarn and weave clothes for the nation, he would not be satisfied’.

Gandhiji then added that they could follow the example of Aurangzeb who made caps for himself by weaving and, very importantly, said: “A greater emperor — Kabir — was himself a weaver and has immortalised the art in his poems.” It is indeed educative that Gandhiji invoked both Aurangzeb and Kabir at the same time for awakening consciousness of the princely classes and those from royal families to take to spinning, an important component of the struggle for independence anchored in non-violence.

Also read: How BJP is becoming its own dangerous enemy

Almost a year later, on October 20, 1921, he wrote in Navjivan about his visit to Rander in Surat district. He found that wealthy Muslims, who earlier were not showing interest in spinning or other activities such as boycotting foreign clothes, had involved themselves in weaving and had started shunning foreign apparel.

He observed, “The notion that a wealthy person need do no work should be banished from our minds…Aurangzeb had little need to work, but he used to sew caps.”

Among the notes the Mahatma wrote in Young India on November 10, 1921, in one note, under the caption ‘A Plea For Spinning’, he reflected on the conditions laid down for civil resisters to weave and use khadi. When some people opposed the conditions on the grounds that it was undignified to do spinning, done usually by women, Gandhiji observed: “The underlying suggestion that a wielder of the sword will not wield the wheel is to take a distorted view of a soldier’s calling…Aurangzeb was not the less a soldier for sewing caps.”

Gandhiji’s many references to Aurangzeb to promote spinning stand in sharp contrast to the manner in which the Mughal emperor is now invoked to create a false impression that there was a clash of faiths in the pre-British period. Such wrong interpretations inflame passions and deepen divisiveness along religious lines.

British divide-and-rule policy

In this context it is illuminating to recall Gandhiji’s speech delivered in Pembroke College in Britain in November 1931. He said that many well-intentioned Britishers wanted to see India free from British rule but apprehended that with the departure of Britishers, India would become a victim of external invasion and get caught in never-ending internal conflicts.

He pointed out that internal conflict and chaos were the outcome of the British policy of divide-and-rule. He pleaded with them to withdraw from India by drawing their attention to the pre-British period, when there were no Hindu-Muslim riots, which became a recurrent occurrence after the commencement of British rule. To drive home the point, he said that we never heard of riots even in the reign of Aurangzeb.

Also read: Madurai and the making of the Mahatma and his Khadi revolution

Again, while speaking at the plenary session of the Round Table Conference in London, on December 1, 1931, Gandhiji said that “Hindus, Mussalmans and Sikhs were not always at war during pre-British era, and with the onset of British rule and the policy to divide people along religious identities, such conflicts became more frequent”.

He stated that both the Hindu and Muslim historians in their accounts of pre-British era wrote about the peaceful coexistence of people of diverse religious persuasions during that period.

Against this backdrop, Gandhiji recalled Maulana Muhammad Ali, who claimed that he would prove “…through documents that British people have erred, that Aurangzeb was not so vile as he has been painted by the British historian; that the Mughal rule was not so bad as it has been shown to us in British history”.

As the process is on to celebrate the 75th anniversary of India’s independence and leaders representing the Government of India are talking ad nauseam about Amrit Kaal in the context of such celebrations, we need to recall the pre-British period outlined by Gandhiji to counter the distorted interpretation that our country suffered slavery for 1,200 years.

Out of such a deliberately flawed understanding of history, attempts are being made to divide people on Hindu-Muslim lines and further intensify that divide around Gyanvapi Mosque and Kashi Vishwanath Temple.

Gandhiji on Gyanvapi Mosque and Kashi Temple

In this respect, Gandhiji’s articulations of 1926 on the temple-mosque issue of Benaras are of added relevance so that communal amity, being constantly assaulted by the powers that be, is safeguarded and enriched.

In 1926, a correspondent wrote to Gandhiji, “Witness the site at Kashi (or Benares) where had stood the temple of Vishwanath for long centuries, since even before Lord Buddha’s time — but where now stands dominating the ‘Holy City’ a mosque built out of the ruins of the desecrated old temple by orders of no less a man than the ‘Living Saint’ (Zinda Pir), the ‘Ascetic King’ (Sultan Auliya), the ‘Puritan Emperor’— Aurangzeb.” The correspondent then put a sharp question to Gandhiji: “Do these facts mean nothing to you Mahatmaji?”

In his reply, published in Young India on November 4, 1926, Gandhiji wrote, “These facts do mean a great deal to me. They show undoubtedly the man’s barbarity. But they chasten me. They warn me against becoming intolerant. And they make me tolerant even towards the intolerant.”

His resolve to become tolerant even towards the intolerant and, that too, on being informed about the alleged barbarity associated with the demolition of Kashi temple and construction of a mosque there, represents the spirit of reconciliation by completely eliminating any desire for revenge. What he said constituted a celebration of higher values rooted in non-violence and respect for the faith of others. It, in fact, upheld the wholesome idea of reconciliation, accommodation and understanding, which remain the foundational pillars of the idea of India.

Such values remained central to the understanding of the Mughal era and the pre-British period in India. Now, when these values and foundations are getting endangered by the ruling leaders saying that history would be rewritten by them because only Mughals got prominence in history books, we need to recall that spirit of reconciliation articulated during the freedom struggle and nip in the bud revengeful and polarised persuasions of those wielding power.

(The writer was Officer on Special Duty and Press Secretary to former President KR Narayanan)

(The Federal seeks to present views and opinions from all sides of the spectrum. The information, ideas or opinions in the articles are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Federal.)