New law or not, lynch mobs need to be brought to justice

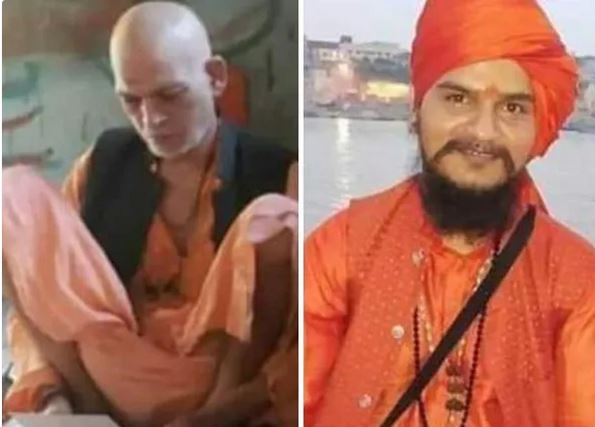

The gruesome lynching of two innocent Hindu monks and their driver in Maharashtra’s Palghar district on April 16, not only calls for the enactment of an anti-lynching law, but also to use existing laws to bring offenders to justice until the former comes into force.

Calling such incidents as “horrendous acts of mobocracy” the Supreme Court in 2018 asked the Centre to consider enacting a new law that sternly deals with mob lynching and cow vigilantism. While the Centre is yet to come up with a comprehensive penal law, the present laws are not awfully insufficient to deal with this joint crime by mobs.

Three laws that make offenders accountable

In most cases of lynching, the invisibility of the mob is often cited as the reason behind offenders going scot free. In the Palghar incident itself, more than a hundred people from a tribal community battered the two monks and their driver to death and beat up a few policemen who tried to intervene. Media reports said 2019 itself saw as many as 250 cases of mob lynchings in the country.

Difficulty in tracing individual members of a mob should not amount to immunity for killing. Section 34 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) incorporates the concept of “joint liability,” saying, “when a criminal act is done by several persons, in furtherance of the common intention of all, each of such persons is liable for that act in the same manner as if it were done by him along”. According to the law, if a hundred people contributed to the injuries of one victim after having conspired together, each of them will be guilty as if he alone caused death of victim.

Related news: Villagers lynch three on suspicion of being thieves

Another occasion which can punish mob for lynching is ‘abetment’. Whoever abets another to commit an offence, will also be liable for that offence.

The third principle, sufficient to punish lynching is ‘criminal conspiracy’. Section 120A says conspiracy, takes place when two or more people get together and plan to commit a crime and then take some action toward carrying out that plan, making it an offence. This means conspiring to lynch itself is an offence. If the conspired offence is committed, each offender is liable for the crime. 120B prescribes punishment with death or rigorous imprisonment.

These three principles make individuals in a group liable of a jointly-committed crime, without strictly examining each person’s injurious contribution to death of the victim. For instance, under the principle, a driver of a robbery gang will be equally liable for murder or grievous hurt committed by his team members while robbing the bank, although he was not physically involved in the physical assault.

Invoking law to prevent lynching

If authorities are proactive, the provisions under the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC) and Indian Penal Code (IPC) can avert incidents of lynching by preventing assembly of a mob in the first place. Under Section 129 of CrPC, any unlawful assembly or any assembly of five or more persons likely to cause a breach of public peace, can be dispersed by command of any executive magistrate or an officer in-charge of a police station or a police officer, not below the rank of a sub-inspector by use of civil force.

If it gets difficult to disperse the crowd, the executive magistrate can call the armed forces to help disperse the crowd by invoking Section 130 (1) of CrPC.

Related news: Palghar lynching: Accused held, Uddhav against communal twist

According to Section 141 of IPC, unlawful assembly is an assembly of five or more people having a common object to perform an offence.

Similarly, Section 144 of CrPC gives executive magistrates the “power to issue order in urgent cases of nuisance or apprehended danger,” which can be used to prevent unlawful assemblies which are determined to commit offences.

Supreme Court’s directions

Taking note of the string of lynchings in the country, the apex court in its July 2018 order had also told states that certain guidelines and preventive measures need to be implemented to stop such incidents.

In Tehseen S Poonawalla vs Union of India and Others (2018), the Supreme Court asked state governments to designate a senior police officer, not below the rank of Superintendent of Police, as nodal officer in each district, for the purpose. The top court order said the home department of states shall issue directives/advisories to the nodal officers to prevent such crimes. The officer will be required to form a special task force that will collect information of people likely to commit crimes or those involved in spreading hate speech and fake news, both online and offline.

The Supreme Court directed that in case of a lynching, police under whose jurisdiction the crime occurred shall immediately lodge an FIR.

It also asked state governments to prepare a lynching/mob violence victim compensation scheme in the light of the provisions of Section 357A of CrPC within one month from the date of the judgment.

The court warned that if police officers or officers of the district administration fail to comply with the directions and prevented investigation or expeditious trial of any crime of mob violence and lynching, the same shall be considered as an act of deliberate negligence and/or misconduct.

The Supreme Court wanted all the directions be implemented within four weeks.

Bills in pipeline

While states like Manipur and Rajasthan have introduced anti-lynching laws, the Uttar Pradesh Law Commission under the chairmanship of Justice AN Mittal in July 2019, published a draft bill on lynching recommending up to life imprisonment for the crime.

According to National Human Rights Commission data, Uttar Pradesh accounted for 869 of 2,008 registered cases where minorities were harassed including lynching, between 2016 and 2019.

The UP law commission due to unavailability of organised data could only collect information about 50 incidents of mob violence in the state in the past eight years. The killing of Mohammed Akhlaq in Dadri in 2015 and inspector Subodh Singh in Bulandshahr in 2018 among other incidents were referred by Justice Mittal, who concluded that the existing law is not sufficient and emphasised the need for a separate law to punish mob lynching crimes. The commission also suggested up to three-year punishment to social media criminals who are liable for disseminating provocative and offensive materials.

Related news: None of 101 arrested in Palghar violence is a Muslim: Maha home minister

The commission drafted the ‘Uttar Pradesh Combating of Mob Lynching Bill, 2019’, which is heavily based on the suggestions of the Supreme Court in Teshseen Poonawalla’s case and legislations from South Africa and Nigeria. The bill suggests punishments ranging from seven years in jail to life imprisonment for the offence, as well as imprisonment for a year for any policeman or district magistrate who fails to prevent incidents of lynching in their jurisdiction. Taking note of the role of social media, the bill also prescribes a punishment of up to three years for dissemination of offensive material.

Proving a prior or on the spot formulation of common intention is the challenge before the police, whether under old IPC or new amendment, if they bring.

In 2017, it was senior Supreme Court advocate and Rajya Sabha MP KTS Tulsi who proposed a private bill “the Protection from Lynching Bill”. The bill which has been pending with the Rajya Sabha since, was last year passed by Rajasthan as an Act.

Section 2(c) of the bill defines lynching as an “act or series of acts of violence or aiding, abetting or attempting an act of violence, whether spontaneous or planned, by a mob on the grounds of religion, race, caste, sex, place of birth, language, dietary practices, sexual orientation, political affiliation, ethnicity or any other related grounds”.

The Palghar lynching may not come under the ambit of the definition, but is based on the “wrongful belief” that the victims were kidney thieves. Manipur’s anti-lynching law covers this aspect.

The draft bills of KTS Tulsi, Manipur and Rajasthan as well as the UP draft bill also have provisions to punish police officers for dereliction of duty, or negligence, while mandating immediate registration of FIR in mob lynching cases, preventive measures, protection of witnesses, and compensation for victims.

While the bills of Manipur and Rajasthan need to be approved by the President, the Union Home Minister told the House that a committee under BPRD has been formed to recommend amendments to IPC and CrPC.

(The writer is a former Central Information Commissioner and Dean of Law in Bennett University.)

(The Federal seeks to present views and opinions from all sides of the spectrum. The information, ideas or opinions in the articles are of the author and do not reflect the views of The Federal.)