Court could have been magnanimous in Prashant Bhushan case

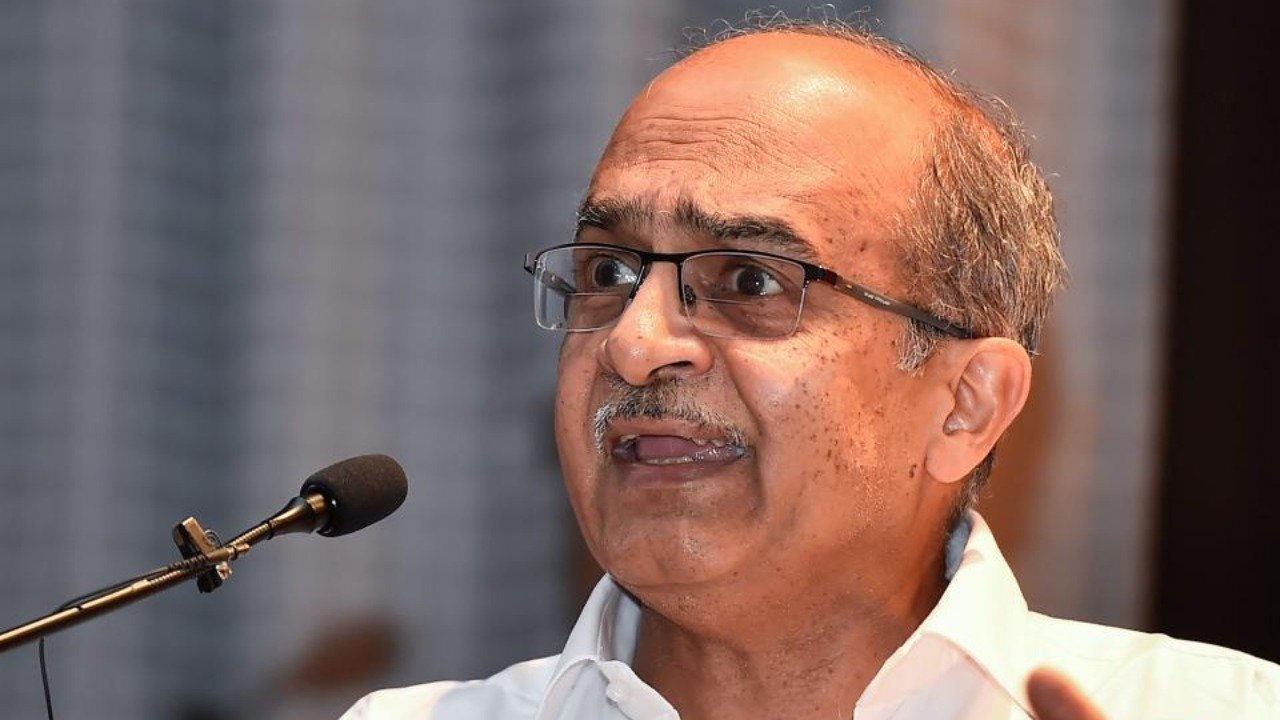

The Supreme Court holding lawyer-activist Prashant Bhushan guilty of contempt of court for his two tweets sent out in the last week of June 2020 is on expected lines.

The Supreme Court holding lawyer-activist Prashant Bhushan guilty of contempt of court for his two tweets sent out in the last week of June 2020 is on expected lines. Mr Bhushan’s tweets, as quoted in the judgment, referred to the (a) conduct of the sitting Chief Justice in a given context; and (b) how historians when in future look back at the last six years to see how democracy had been destroyed in India even without a formal Emergency, they would particularly mark the role of the Supreme Court in this destruction, and more particularly the role of the last four Chief Justices of India.

The facts that emerge from the chronology of events show that the Court at some point of time decided to consider this matter expeditiously. It also decided to consider it suo motu (on its own). The reasons for such expeditious suo motu Court intervention were not clear from the 108 page judgment that was handed out on Friday (August 14). Justice Arun Mishra, one of three judges of bench and the senior most judge of the Court (third in seniority), retiring on September 2, 2020 could be another notable point for the expeditious trial. The sentencing of Prashant Bhushan is now posted for August 20. It took just two months for the Court to deliver this verdict. Another contempt case against Prashant Bhushan filed in 2009 is still awaiting conclusion.

The highest Court of the land generally does not take up matters suo motu unless it is extremely necessary for it to intervene in the public interest.

Besides the Contempt of Court Act, 1971, the Supreme Court has the Constitutional mandate to act as the Court of Record and has enormous powers to decide any matter that impedes the administration of justice and questions the authority of the Court. The present judgment refers to a plethora of cases decided by it that provide the broad interpretative matrix as to what is the scope of the phrases ‘administration’ and ‘authority’ of the Court. All the earlier verdicts quoted in the judgement clearly point out the context and the external factors that lead to the decision in any given contempt case. If the reference is made in the personal context of a judge, it is clear from the cited judgments, the Court has no jurisdiction to entertain such a contempt petition.

Given the enormous judicial power and Constitutional mandate, the highest Court of the land has a special responsibility to guard against the arbitrary exercise of power by other wings of India’s democratic set up such as the Executive (the Government) and the Legislature. This is the Constitutional scheme and the Supreme Court (upto a point High Courts) has the power to balance and protect the rights of the citizens, especially the vulnerable and marginalised sections of the society.

It is, therefore, obvious that those who study the working of the Constitution and its historical role in dealing with the emerging challenging and complex situations within our country hold the Court responsible for doing or for not doing something in any given context or time period.

India has a political and constitutional history of more than seven decades. In all these years the Indian Supreme Court, no doubt, has played an important role in shaping the lives and times of the Indian people. It is also equally evident and clear that in many of the earlier historical and political contexts the Indian Supreme Court buckled under pressure and failed to live up to its given Constitutional mandate. These have been well recorded and written about by many scholars in India.

Therefore, an expression of mere anguish towards failure of earlier six Chief Justices in dealing with prevailing Emergency-like situation ipso facto should not warrant a criminal contempt against Prashant Bhushan. This would be against the basic tenets of the Constitution that guarantees freedom of speech and expression as guaranteed under Article 19 (1). The Court should be magnanimous enough to balance this Article 19 (1) right with the reasonable restrictions as incorporated in Article 19 (2).

This larger question needed more consideration. However, the Court spent just one small paragraph on this issue without getting into the larger ramifications of its curtailment. In fact, the much larger question is – how a court against whom such allegations are made could decide the matter of contempt judicially on its own? The basic provisions of the Contempt of Court Act, 1971 to that extent are in violation of the basic procedural issues relating to the principles of natural justice. To simply put it, one cannot be a judge in one’s own cause which is known by the Latin maxim Nemo judex in causa sua i.e, no one is judge in his own cause.

Take for example, the working of the American Constitution in the last 200 years or more. It has gone through various vicissitudes and upheavals. Many path breaking decisions of the American Supreme Court, even in the context of criticism, to uphold the liberty of freedom of speech and expression should be taken into consideration.

Even the Indian Supreme Court, in some of its celebrated dissenting opinions, has gone on to celebrate the majesty of its freedom and justice in protecting the rights of ordinary citizens. But, the invoking of its robust independence in dealing with or not dealing with (or delaying as alleged) in certain matters in recent years is a matter of concern to many. It is creating a perception that the Court needs to battle. All of us, including lawyers of all hues, have stake in this as it is the Court that provides us the last refuge from the arbitrary exercise of power.

The confirmation of criminal contempt against Prashant Bhushan must be seen in the above light. He, like scores of eminent lawyers, academics, journalists and others, for over three decades has strived for building an independent and robust judiciary. The Court, hopefully, will take into account these factors while taking a decision in sentencing him. This is a major challenge for the Court to overcome and restrain its own enormous powers to protect the larger freedom of speech and expression.

(Venkatachala G Hegde teaches at the Centre for International Legal Studies, School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi)

(The Federal seeks to present views and opinions from all sides of the spectrum. The information, ideas or opinions in the articles are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Federal)