British left behind a ‘Himalayan’ mess; India, China still fighting over it

In the midst of the ongoing standoff between India and China in the Ladakh region, Beijing recently made an intriguing offer to New Delhi – to recognise as boundary a version of the Line of Actual Control drawn up in 1959 by the then government under Chairman Mao.

In response, the Indian government peremptorily rejected the offer. Defence Minister Rajnath Singh in Parliament said, “As yet there is no commonly delineated Line of Actual Control (LAC) in the border areas between India and China and there is no common perception of the entire LAC.”

A perusal of the 1959 Chinese offer and the various boundary lines in the Ladakh region that were drawn between the two countries in colonial India shows capriciousness on the part of the British. Had the British not ventured into drawing boundaries, probably free India and Communist China would have sorted the issue without much ado.

As with several other areas of the world, it was the British who created confusion here as well with a multiplicity of maps, borders and lines – none of which was definitively accepted by all parties concerned. The British left in 1947, leaving complex and conflicting claims that until today has left two large nations in a perpetual state of mutual hostility.

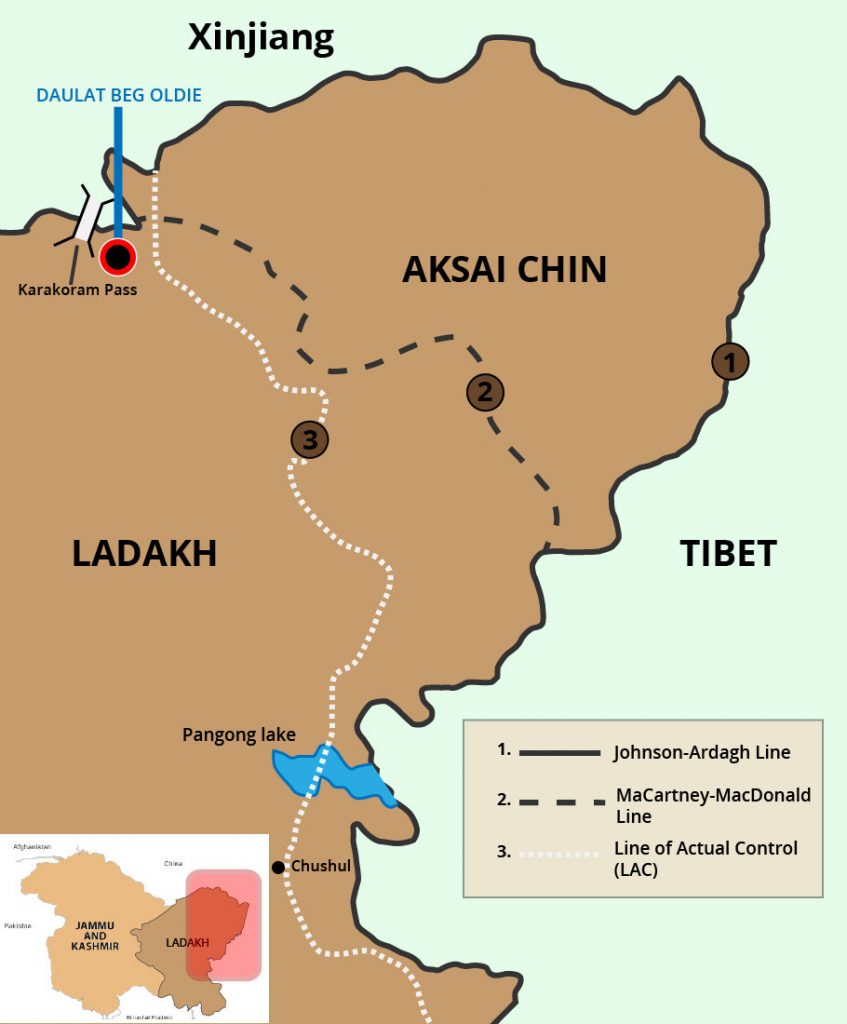

The first attempted boundary line was by a British civil servant WH Johnson in 1865, which marked Jammu and Kashmir along with Aksai Chin as part of India. Also called the Johnson Line, the British government discounted it as there were inaccuracies in the map.

A few years later, this map was modified by a British military officer Sir John Ardagh. The Johnson Line became the Johnson-Ardagh Line. The Chinese did not acknowledge this. The British, in 1899, further worked on the border map to come up with the MaCartney-McDonald (M-M) line which approximately divided the Aksai Chin area between India and China.

Until 1958, China unofficially accepted this line. But, going by reports of that period, on the ground it seemed more like no-man’s land with Indian troops patrolling many points within Aksai Chin and Chinese troops too patrolling in the same area that India considered its territory.

Despite being responsible for drawing these boundary lines, the British did not pursue any of these to their logical conclusion, which would have been to sign an agreement with the Chinese rulers. Eventually, it was the third line drawn in 1899 that remained, but without any formal acquiescence by Beijing.

Related news: If Russia plays a role, peace between India, China can be salvaged

With the British neglecting to convert the M-M line into a formal border, not surprisingly it turned into a dispute after India’s independence in 1947 and the coming to power of the Communist party in China two years later. Each government had its own interpretation of where the boundary line lay.

India chose to go with the Johnson line while the Chinese opted for the M-M line. In other words, in New Delhi’s perspective Aksai Chin belonged to India while Beijing viewed this as a part of China.

The irony is that large tracts of the Himalayas are under minimal habitation. They mostly act as a natural barrier between the two countries due to the treacherous terrain, inhospitable climate and the daunting mountain ranges that, if at all, inspire awe and are a sight to behold.

At the end of the day, one wonders what India and China are squabbling over? There is as yet no discovery of oil or any other underground natural resource in the region. Much of the vast expanse of the land claimed by India and China is unpopulated and cannot be productively used. If at all, they can be of strategic importance in a conflict situation, which becomes redundant if there is a mutual agreement.

Unfortunately, common sense and logic haven’t played a role on both sides. Instead, the difference in perspective came to a head in the 1950s when the time came for drawing up a boundary line. It is in this context that the then prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Chinese premier Chou-en Lai exchanged notes in 1959. Beijing proposed a “Line of Actual Control” (a takeoff from the M-M line) which Nehru angrily rejected.

The official map of independent India (which continues to be used even today) under Nehru’s instructions had already included Aksai Chin (as per the Johnson line) as part of Jammu and Kashmir. The Indian government refused to budge from this position.

The bonhomie that had existed from 1950 evaporated in 1959 and was replaced by rising tension over the interpretation of the boundary line.

The situation turned serious when India discovered that China had unilaterally built a 1200 km road linking Sinkiang with Tibet which ran across Aksai Chin. For the Chinese, which went by the M-M line, this was entirely legal. But, it conflicted with New Delhi’s claim as per the original Johnson line that had placed the whole of Aksai Chin within India.

War broke out three years later in October 1962. By the time fighting ended a month later China had occupied the area it had demarcated in its 1959 proposal. Aksai Chin was taken over completely.

From then until now, this is largely the situation. The Chinese have remained in an area just to the north of Galwan valley. To add salt to India’s wound, Pakistan ceded to China territory abutting the Karakoram pass it occupied in the 1947-48 conflict with India

Related news: In the event of an armed conflict, both India, China stand to lose

For China, the western sector is not merely a boundary issue as the restive Tibetan region lies alongside Ladakh. From Beijing’s view, it makes Tibet more secure if there is a buffer around it which is why it is sensitive about Ladakh. Incidentally, Chou-en Lai’s LAC proposal also coincided with the Chinese Army’s occupation of Tibet in 1959, and the fleeing into India of the Dalai Lama and Tibetan insurgents.

So, when China offers to turn the 1959 LAC as a boundary, it is basically asking New Delhi to give up its claim to the areas that India lost in the 1962 war. For India, accepting the 1959 LAC means formalising a defeat and having to change the official map accordingly. This is bound to send the shivers through any government in New Delhi, and hence the reluctance to play ball with the Chinese.

But, if the Indian government were to bite the bullet and agree to the 1959 LAC offer as a permanent boundary, chances are the border dispute will die down. China, has in the past indicated it will give up its claim over territory including Arunachal Pradesh in the eastern sector and settle for the McMahon line as the permanent boundary provided India recognises the 1959 LAC.

However, given the underlying mood of mistrust (which has now boiled over to open hostility) that exists between the two countries despite a robust economic relationship it would require statesmanship of a high order to talk peace and sign on the dotted line.