Beyond Hindu-Muslim binary: The Buddhist Claim on Ayodhya

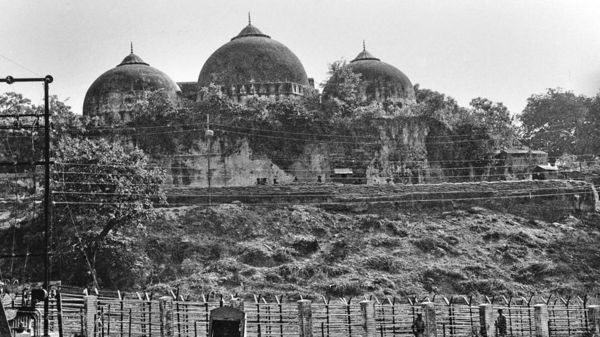

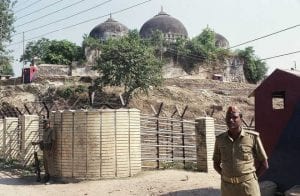

The Babri Mosque-Ram Janmabhoomi land dispute may have reached its climax after a 140-year-long legal battle. But has it really ended? Is the verdict really about ‘equity and good conscience’ as pronounced by the Supreme Court? Was the mob which demolished the mosque right in its claim? Has the unanimous judgment by a five-judge constitution bench favoured the majoritarian faith or is it really based on the strong archaeological evidence?

Several ambiguities rise after reviewing the verdict. The apex court cited an Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) report and concluded that “the underlying structure was not an Islamic one.” Meaning, the original structure was built in pre-Islamic times.

The ASI, however, has not established the existence of any Hindu temple. If one goes by the verdict, which has based on ASI findings, it becomes clear that the bench was preoccupied with the conventional Hindu-Muslim question and not available evidence.

However, the truth, one could argue with good reason, lies beyond this temple-mosque binary. The ASI believes that there is strong evidence showing a Buddhist link to the site, where the mosque was demolished.

Ayodhya signifies a great importance in the Buddhist literature. It is referred to as Saket in traditional Buddhist literature. British archaeologist Alexander Cunningham who was also the first director general of the ASI identified three Buddhist places — Mani Parbat, Kuber Parbat and Sugriv Parbat at the site of Ayodhya.

Also read | Three trusts stake claim for Ram temple construction in Ayodhya

Cunningham identified Mani Parbat and Kuber Parbat as stupas and Sugriv Parbat as a Buddhist monastery. One can also infer the existence of Buddhist structures in Ayodhya from the records of Chinese travellers Xuanzang and Faxian. John E Hill (2004) in his book, ‘The Peoples of the West from the Weilüe Yu Huan: Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265 CE,’ noted that Ayodhya (then Saket) was ruled by the Buddhist Kushan Emperor of India in c. 127 CE.

Following such significant historical evidence and facts, Vineet Kumar Maurya, a resident of Ayodhya and an Ambedkarite Buddhist had filed a writ petition in the Supreme Court in March 2018 claiming that excavations at the disputed site had unearthed remains from the Ashokan era linked to Buddhism.

Although the Supreme Court heard the petition, it was not considered significant as the temple-mosque binary or ‘matter of faith’ was the primary basis for the judgment. Question remains, if the judgment was based on the non-Islamic or pre-Islamic evidence at the disputed spot then why did the Buddhist claim gain no importance?

Was the judgment about reviewing the evidence scientifically or was it about proving that there exists the ‘Hindu Collective Consciousness’? Was it really about the demolition of a temple by Muslim invaders or is it about the appropriation of Buddhist stupas by Brahmin priests?

Also read | Evolutionary logic and history contradict belief Rama was born in Ayodhya

History from the margins speaks differently

Balwant Singh Charvak a known Dalit-Ambedkarite intellectual from north India in his book ‘Ayodhya Kiski? Na Ram Ki, Na Babar Ki’ (Whose Ayodhya? Neither Ram’s Nor Babar’s) – argued that there is no evidence of the existence of a Ram Temple at the disputed site. He, however, like other Ambedkarite scholars argued that the disputed spot was a worshiping site for lowered castes who according to him were the early Buddhists.

Charvak writes that the spot was a grand Buddha Vihara. He further argues that with the decline of Mauryan kingdom and murder of the last Mauryan king by the Brahmin king Pushyamitra Sungha, Buddhism also perished in first century BC. With an intention to revive Brahmanism, King Pushyamitra Sungha ordered the massacre of Buddhist monks as well as the destruction of Buddhist Viharas, Buddhist cultural and learning centers.

Brahmin not Babar demolished Buddha Vihara

When Babar or his general Mir Baqi arrived in Ayodhya there were only Buddhist ruins left scattered. According to Balwant Singh Charvak, Babar had built what is known as Babri Masjid with the scattered Buddhist ruins. Therefore, it was not Babar or Mir Baqi who destroyed or invaded the Buddha Vihara at Ayodhya but it was Brahmin king Pushyamitra Sungha and other Brahmins, writes Charvak.

Importantly, such understanding of Indian history goes beyond the mosque-temple binary and poses a strong opposition to the Brahamanical supremacy.

In his attempt to reformulate the erstwhile untouchable’s past, Ambedkar made historical departure from the conventional arithmetic of Hindu v/s Muslim. While tracing the roots of untouchability, Ambedkar in his text ‘Revolution and Counter-Revolution’ in the destruction of Buddhism by Brahmins and Brahmanism, he stated that India’s history is “nothing but a history of mortal conflict between Buddhism and Brahmanism.”

Nevertheless, conventional history of India’s religious life remained wedged in the Hindu-Muslim conflict. This binary later became more obvious specifically in the post partition era. Thus, the discussion around religions like Sikhism, Jainism and Buddhism remained mostly in the realm of spirituality.

As a result of having fewer followers in India, Buddhism’s relevance was largely limited to a few ancient historians and students of religious philosophy. In 1956, Ambedkar reintroduced Buddhism as an organised religion in India by converting to the faith with lakhs of erstwhile untouchables.

Soon, Buddhism as a religion became a significant part of the anti-caste movement in general and the Dalit movement in particular. Ambedkar reviewed the Buddhist past as a path against Brahamanical traditions and held counter-revolutionary Hindus responsible for its decline in the country of its birth.

Following Ambedkar’s step, many anti-caste scholars and activists have attempted to frame the evolution of religious life in India through a Buddhist lens. Reinterpreting historical facts, anti-caste scholars argue that major temples like Bhuteshwar and Gokarneshwar in northern India, Jagannath temple at Puri, Sabarimala Ayyappa temple in Kerala, the Tuljabhavani temple in Maharashtra, Shaivite temple at Bodh Gaya many more Hindu temples in different parts of the country are appropriation of local lower caste deities and Buddhists sites.

DC Ahir — a notable Ambedkarite and Buddhist scholar in his books ‘Buddhism in South India’, ‘Buddhism in Modern India’ and ‘Buddhism Declined in India’, has detailed how Buddhist shrines in various regions of the country have been appropriated as Hindu temples by Brahmins.

Buddhists the first ‘religious other’

For this reason, the anti-caste movement believes that the Buddhists were the first ‘religious other’ in a society created by the Vedic-Brahmin-Hindu ideology. This led to the persecution of Buddhist sites and followers. In contemporary times it is Islam and Muslims who have become the immediate ‘religious other’ and are facing the same fate what Buddhism met in the past.

The claim of Ayodhya site as a Buddhist Stupa or Vihara, was never backed by an organised mass.

Also read | AIMPLB to seek review of Supreme Court’s Ayodhya verdict

Although the Buddhist history of Ayodhya is a subject of passionate conversation in the anti-caste movement, never has there been any movement by any socio-political Ambedkarite Buddhist organisation for the reconstruction of the stupas and Viharas that were destroyed by Pushyamitra Sungha. The anti-caste Buddhist claim is about the reconstruction of Buddhist history rather than reconstruction of Buddhist sites.

(The author is a PhD candidate in sociology at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.)

(The Federal seeks to present views and opinions from all sides of the spectrum. The information, ideas or opinions in the articles are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Federal.)