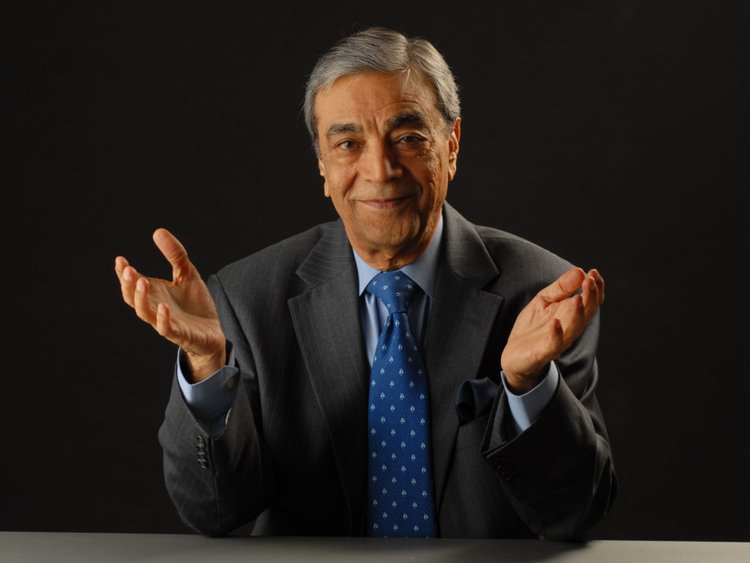

Zia Mohyeddin: A thespian, a showman and a passionate storyteller

Zia Mohyeddin (1931-2023), the British-Pakistani thespian, who juggled acting, direction and broadcasting, passed away on Monday at the age of 91. A virtuoso, an aesthete, a storyteller and a raconteur, he revelled in the expanse of language, ever attuned to its inflections and nuances. He also had the distinction of being the first from his country to have lived his Hollywood dream.

How do you encapsulate a life as richly lived as Mohyeddin’s, a life spent in the service of performing arts and literature? I’ll attempt this in the light of his work. Before his death, Russian playwright and master of short stories Anton Chekhov wrote to his wife: “You ask me what life is? It’s like asking what a carrot is. A carrot is a carrot and nothing more is known.” Mohyeddin saw modern life as a carrot, “devoid of graciousness and shorn of the past and unheedful of the future,” he wrote in A Carrot is A Carrot: Memories and Reflections (2011), a collection of short essays, in which he ruminated on, among other things, his father, his discovery of the Western world and his undying love for language and literature.

A Life Less Ordinary

Before Mohyeddin became the president of the National Academy of Performing Arts when it was founded in Karachi in 2005, he had journeyed through the world of acting and direction in England and America for nearly fifty years. Having been trained in theatrics at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts in London (1953-1956), he was part of a theatrical production of Julius Caesar in 1957 and made his West End debut with the role of Dr Aziz in A Passage to India in 1960.

Mohyeddin made his film debut with the British classic, Lawrence of Arabia (1962), directed by David Lean, in which he played Tafas, the ill-fated Arab guide of Lawrence (Peter O’Toole). Also featuring Omar Sharif, the film marked Peter O’Toole’s film debut and fetched him his first Oscar nomination. It catapulted Mohyeddin to fame and soon other films followed, including Fred Zinnemann’s Behold A Pale Horse (1964) and Jamil Dehlavi’s Immaculate Conception (1992).

Also read: For Balkrishna Doshi, architecture was an instrument for the greater good

As an actor and director, Mohyeddin had his share of triumphs and setbacks, but it was all, in the end, worth it. “The compulsive irrational human instinct — the Need to Act — gives rise to more disappointments than anything else, but I’d rather live through these than own a chain of Wal Marts…. The moment of elation as you step forward to take a bow and hear the surge of applause rise to a crescendo, compensates for all the frustrations that a theatrical career, necessarily, entails,” he wrote in A Carrot is A Carrot.

The Sound of Music and Words

Mohyeddin owed his love for the sound of words and literature to his father, Khadim Mohyeddin, a senior lecturer of English at Punjab University in Lahore. An amateur musician, Khadim spent most of his early life in the intense pursuit of music and could play Tabla, Dilruba and Harmonium. Later, as a lecturer, he spent all his spare time in trying to enlist support to have classical music introduced as one of the subjects in Punjab University.

In his heyday, Khadim was also fuelled by nationalism. He had famously burnt his English clothes and joined the Khilafat movement (1919-24), wandering in and around what was then known as Poona, trying to acquire musical knowledge from the gurus who lived in Maharashtra. When he died, Zia Mohyeddin discovered, among his father’s papers, a little black book, yellowed with age, in which he had put down more than 175 bandishen (songs set in ragas, with strictly codified ascending and descending modes), the date when he heard these renditions, as well as the rhythmic cycle which laces these compositions. That little book was one of Zia’s dearest possessions.

Also read: Mary Roy, the indomitable fighter who lived on her own terms

After Partition cleaved lands, and hearts in 1947, it made Khadim embittered and testy. He stopped believing in human kindness. To add to his woes, the newly-established Radio Pakistan in Lahore came under a cloud for broadcasting music that was ‘infidel’ in name. So, overnight, ragas like Shiv Ranjini and Saraswati were proscribed, leaving musicians bewildered about what was kosher and what was not. The impassioned clerics stressed that musicians should only concentrate on raga Aiman, seen as the greatest of all the ‘Muslim ragas.’ Of course, the clerics never cared to find that in scale and structure, the musicians were only playing the Raga Yaman, which had been sung in India for thousands of years.

It was his father who kindled in Zia a love for English literature and the musicality of words, which he would later hone as an actor and a reciter of verses.

Poetry Recitation

In recent years, Zia had come to be known as an indefatigable and fastidious reciter of verses, who took the beauty of Urdu poetry to the masses. In the subcontinent, poetry, he always said, was not so much recited as hammered (he used the Urdu word, bhanbhorna for this). “The readers (as well as most poets) thump out each line as if it stood by itself, irrespective of the rhythm of the following line or lines. The temptation of stressing and pointing out the rhyme is too strong for them to resist. The rhyme should be heard clearly, but if the phrase does not require any pause, the reader should go on to the next line without one,” he’d say.

Also read: ‘Rishi Sunak: The Rise’ review: The success story of a minority in Britain

The fault lay, he underlined, with the false notions we have about our system of scansion. Most reciters think that because the lines rhyme, they have to intone them if not to sing them outright. Poetry reading, he pointed out, had become akin to the rhetoric that emanated from the pulpit. It may mesmerise some listeners, just as sermons do, but it demeans the colour and music of the words which the poet has, intuitively, (or consciously) arranged as the vehicle of a particular experience.

“Poetry does not sound better or more meaningful if you were to scan it technically or more meaningful if you were to scan it technically. Most people, when they set out to recite poetry to a gathering, confuse the inherent rhythm of a poem with its meter. Rhythm is the actual movement of the words and this is rarely in agreement with the beat of the meter. The expressiveness of the verse depends upon the variations of the rhythm and the artful use of inflections. Naturally, you cannot disregard the prosodic arrangement,” he wrote in one of his essays.

The first duty of a reciter, according to Zia, is to understand and respect the poem he recites: “If he is serious about his work, he should try to train himself as to speech and voice; only then will he be able to develop a perception about phrasing, tone and clear, well-formed sounds. A training in rhythm is also necessary as well as the precise and rapid articulation, correct pronunciation and a range of tone and timber. A capable reader of poetry must give the effect of spontaneity and ease. Laboured speech kills the subtlety of fine poetry.”