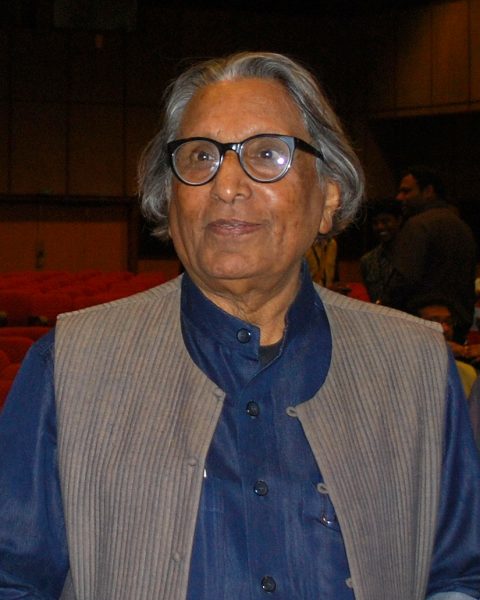

For Balkrishna Doshi, architecture was an instrument for the greater good

Balkrishna Vithaldas Doshi, India’s first winner of the Pritzker Prize — considered to be the architecture’s equivalent of the Nobel Prize — passed away on Tuesday at the age of 95. The architect, urbanist and educator, who has been awarded the Padma Vibhushan posthumously, leaves behind an enviable legacy that will be onerous for modern architects to emulate.

The bulwark of Doshi’s architectural philosophy was an interplay of tradition and modernism, an interrelationship of indoor and outdoor space, an abiding concern for the climate and an insatiable urge to blend the old and the new, the regional and the universal.

Architecture for greater good

During his career spanning seven decades, which included the turbulent years of post-Independence, Doshi emerged as a champion of low-cost housing for the country’s poor. Architecture, for him, became an instrument for the greater good. He created new forms that were as much embedded in social, historical and cultural awareness as they were in the enduring values of modern architecture. His philosophy reflected the desire to establish links between the community and nature.

Born in Pune in 1927, Doshi came of age in the era immediately after Independence during which the leaders of the country were confronted with the mammoth task of building the nation. If Jawaharlal Nehru had the vision of an industrial future, which combined liberal democracy and technological prowess, Mahatma Gandhi saw a village as a repository of values. Doshi struck a balance between the industrial town with the unmistakable signs of progress and modernity, and the pristine, uncorrupted rural landscapes untouched by the urban chaos.

Also read: How Indian queens across history scripted stories of valour and victory

Having seen extreme poverty as a child, he remained committed to the idea of social housing. “(In India) we talk of housing, we talk of squatters, we talk of villages, we talk of towns — everybody talks, but who is going to really do something about it? I took the personal decision that I would work for the ‘other half’ — I’d work for them and try to empower them,” he had told CNN in an interview once.

A vocabulary of his own

In the beginning of his career, Doshi worked under modernist master Le Corbusier in Paris in the early 1950s, before he returned to India to oversee Corbusier’s projects in Chandigarh and Ahmedabad. He also counted Louis Kahn, arguably one of the most significant architects of the 20th century, among his friends. He, however, developed a vocabulary of his own, profusely using vaults, shaded courts, grassy platforms, water gardens and hooded sources of light as elements of his style.

Years after he returned from Paris, he settled in Ahmedabad, where he established his practice, Vastu Shilpa Consultants. Guided by his father-in-law, Professor Rasikbhai Parikh, a scholar of Sanskrit, he immersed himself in the study of shilpa (architecture) and established his practice with Vastu-Shilpa Foundation for Studies and Research in Environmental Design. It was in Ahmedabad where he came up with some of his best-known projects: from Tagore Memorial Hall to Amdavad ni Gufa, an underground museum that boasts of a series of domed roofs.

As William J. R. Curtis underlines in Balkrishna Doshi: An Architecture for India (1988), Doshi explored “the mythical and poetic dimensions of nature: the flow of breeze and water, the contrast of light and shade, the relationship between ground and sky, returning to the wisdom of the vernacular, with its timeless solutions for dealing with social space, climate, materials and human scale.”

In harmony with nature

Doshi fused architecture with urbanism and envisioned man in absolute harmony with the natural order. With a penchant for mythological and visionary allusions, he worked towards a synthesis between the values of the East and the West. With dedicated collaborators (since 1977) like Joseph Allen Stein and Jai Rattan Bhalla, as well as Achyut Kanvinde, Doshi designed iconic buildings like the Indian Institute of Management in Bangalore, and Sangath, his own studio in Ahmedabad.

Beginning with Modernist influence in the1960s and early 1970s, his practice was marked by a search for indigenous Indian models till the mid-1980s. In subsequent years, he moved to drawing on the primal, mystic elements of early Buddhism as well as Hindu and Islamic models. The historical, religious and social strands blend well in his works. In IIM Bangalore, for example, he showcases how he absorbed the features of the Islamic palace complexes like Fatehpur Sikri (cascades of terraces, pillared halls, airy pavilions) and Hindu cities like Madurai (strong axes, shaded walls, courts and tanks).

Also read: What has led to the great resurgence of literature from Japan

Doshi remained deeply interested in the evolution of vernacular residential typologies, from the gridiron patterns of Bohravads (the neighbourhoods of the rich Gujarati Muslims) to the ornamental façades (jharokhas or projecting balconies and carved latticework wooden windows) of the old residential precincts or pols of Ahmedabad.

His early association with Corbusier and Kahn, both of whom created an enduring framework that was seen as the high point for everything that followed, made an indelible impression on him. Grappling with the quandary of the Third World — how best to modernise without losing the core of the cultural identity — Doshi’s work is in the same register as those of other architects of the developing world, like Hassan Fathy in Egypt and Rasem Badram of Jordan. He aimed to express “a cosmic relationship” through the internal and external integration of space. His yearning to make local symbolism and associations a part of the aesthetic considerations of design is evident in most of the edifices he designed.

“Architecture should speak of its time and place, but yearn for timelessness,” Frank Gehry, another iconic architect and winner of the Pritzker Prize had said once. In the annals of Indian architecture, Doshi’s body of work symbolises the yearning for timelessness.