Vivan Sundaram: Trailblazer in installation art, pioneer in use of found objects

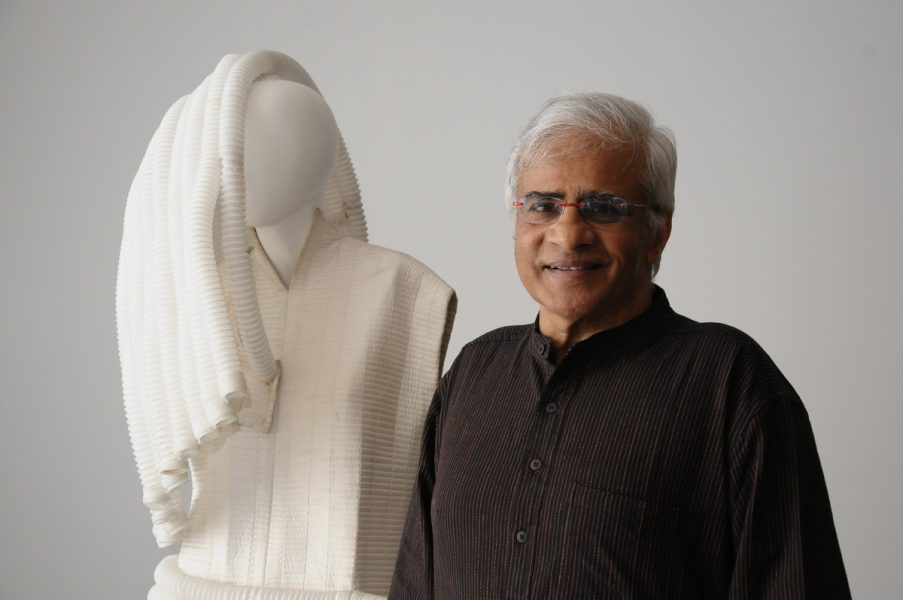

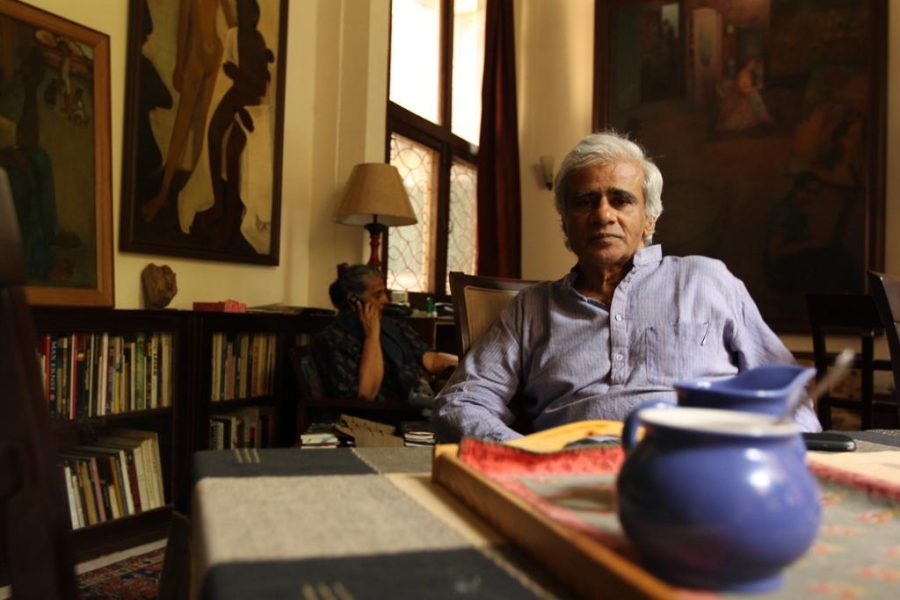

One will always remember Vivan Sundaram (1943-2023) as an artist with iconic shock of white hair and signature black kurta. His quick wit and infectious smile were often tinged with a touch of sarcasm. It’s difficult to come to terms with the fact that the artist, who was a rebel and a vanguard of many important movements, has left us.

On March 29, at 9.30 in the morning, Sundaram departed from the art world — as his body succumbed to the trials he was facing — at a hospital in Delhi; he was battling pulmonary embolism and had been in the hospital for the past few weeks. His cremation was held on Thursday (March 30) at 12 noon, at Lodhi Cremation. Known for his exceptional talent, boundless creativity, and unbridled passion, Sundaram is survived by his spouse, the critic-curator Geeta Kapur.

Sundaram belonged to a group of artists who emerged in the wake of India’s independence in 1947, and who sought to create a new kind of art that was deeply rooted in the country’s complex social and political realities. These artists rejected the Eurocentric model of art that had dominated Indian art schools under British rule, and instead sought to forge a new aesthetic that was grounded in India’s rich cultural heritage.

A pioneer in the use of found objects and a master of assemblage, Sundaram created works that were not just visually stunning, but also thought-provoking. He was a true innovator, always experimenting with new forms and materials, and never afraid to take risks. Most recently, Sundaram was one of 30 artists specially commissioned to make new work to mark the Sharjah Biennial’s 30th anniversary edition.

Also read: Vivan Sundaram, a seminal figure in India’s art scene, dies at 79

The ongoing Sharjah Biennial 15: Thinking Historically in the Present (February to June 2023), conceived by the late Nigerian curator-critic-poet Okwui Enwezor and curated by Hoor Al Qasimi (Director of Sharjah Art Foundation), includes Sundaram’s photography-based project, Six Stations of a Life Pursued (2022), signifying a journey with periodic halts that release “pain, regain trust, behold beauty, recall horror, and discard memory”.

Born in 1943 in Shimla (Himachal Pradesh), Sundaram pursued painting at the Faculty of Fine Arts, M.S. University of Baroda (1961-65) and later at the Slade School of Art, London (1966-68), where he also studied the History of Cinema. While in London, he actively participated in the student movement of May 1968 and helped establish a commune where he resided until 1970. Upon returning to India in 1971, Sundaram collaborated with artists and students’ groups to organize protests and events, particularly during the Emergency period.

Early beginnings

I met Sundaram for the first time in 1996, when I was a student at the Maharaja Sayajirao University Faculty of Fine Arts in Vadodara. As a former student of the faculty himself, Sundaram graciously presented us with a slide show of his work and even shared his idea of reinterpreting the work of his maternal aunt, Amrita Sher-Gil.

The resulting exhibition was a digital reference to the archival imagery of his grandfather, Umrao Singh Sher-Gil (1870-1954), who was a philosopher and self-taught photographer. Through his grandfather’s documentation of his mother, aunt, and wife, Hungarian opera singer and pianist Marie Antoinette Gottesman, Sundaram wove a complex web of relationships into his work.

Sundaram’s Re-take of Amrita, created between 2001 and 2005, featured digital photomontages that blended images spanning three generations. The artwork incorporated not only Sundaram’s family, but also “paintings, mirrors, and household interiors of the period,” collapsing time and space into contemporary fictions.

At that time, I was an inquisitive student and a half-formed critique. It was a welcome surprise when Sundaram patiently answered my queries and encouraged me to continue to think critically. I met him next at Chemould in Mumbai in 2001 when I was working as an arts journalist at The Indian Express.

I wrote about the show Re-take of Amrita at Chemould Art Gallery, which was then situated above the Jehangir Art Gallery. One could say that this was really the beginning of our friendship and his guidance, which remains with me. Whenever we met at art openings, talks, and get-togethers, he gave me critical feedback on my writing and suggested readings on art, not just in India but internationally as well.

Also read: Riyas Komu interview: How art can be a site of political discourse, dissent

Regarding Sundaram’s work on Sher-Gil, art historian Rakhee Balaram writes, “The images created by Sundaram in Re-take of Amrita interweave complex portraits within portraits of the genealogy of a cosmopolitan family. Vivan’s appearance as a small child in one of the photographs, seated on his grandfather’s lap with a Voigtländer camera and surrounded by members of his family at different ages, tells another story. One could say that the image belies an adult Sundaram’s intent, on the one hand, to come to terms with the burden of ‘legacy and a world of which he is unaware except through memory, photographs and paintings’, and on the other, ‘a design in retelling that truth through his own eyes.’ The game becomes as tragic and timely as any epic.”

“In the early 1990s, when one looks back at the breakthrough of mediums, where the norm for artists was working with traditional oil paintings (which Vivan also did), Vivan would be considered one of the earliest “breakthrough artists,” says Shireen Gandhy, who helms Chemould Prescott Road. “Often, artists who paved the way, giving courage to others to walk that path, are considered trailblazers. When it comes to installation art, Vivan was that trailblazer. It was a new term, fairly unknown to the contemporary world,” Gandhy says.

“Vivan’s Marxist ideology, his sense of justice, and his strong politics intersected with his art practice. I will never forget his engine oil drawings (1992) after the Gulf War. It was possibly the first time he broke out of mediums like charcoal, pastels, or oils. These were large works on paper made with engine oil, with trays of oil at the bottom of each work that felt like blood-spill art (and less like an oil spill),” Gandhy recalls.

“The exhibition held at two public spaces — the Shridharani in Delhi and the Jehangir Art Gallery in Bombay (presented by Chemould) — was a revelation to many. Most of these works were sold to collectors of that time. But more than that, my strongest memory was the presence of students during the course of not only the exhibition but also the installation of the show. I think it was a moment of reckoning, both for us as gallerists and for the audience to perceive works in this courageous way,” adds Gandhy.

“I have always had the greatest support, even gentle chiding and guidance, from both Vivan and Geeta. It is hard for me to express how deeply grieved I am. It is not just a loss to the art world, but a personal loss to me. We were working on a book to celebrate 50 years of TAKE on Art, and despite his ill health, Vivan was there with Geeta, giving me guidance. The two would attend exhibitions of young and emerging artists, even in their frail condition. One knows that it is a great loss of such dedication to the arts,” says Bhavna Kakar, editor of TAKE on Art and director of Latitude 28 Gallery.

Flash-Forward

Sundaram was a founding trustee of the Safdar Hashmi Memorial Trust (SAHMAT). He initiated and conceived art projects and curated exhibitions. In his own words, “My politicization in the May 1968 student movement took on a specific ideological orientation by association with comrades from the CPI(M), though I have never been a member of the party. On the art front, there was the setting up of the Kasauli Art Centre in 1976, with its informality, hospitality, and active exchange of organized discourse,” wrote Sundaram.

“As a founding trustee of SAHMAT from 1989, I have been part of some head-on politics in the period, especially from 1990 to 2003. I have curated many small and big exhibitions on behalf of SAHMAT — installed and roving shows — that were exhibited across the country and that engaged with the public domain through innovative formats,” he wrote.

Recalling Sundaram’s words and expressions, one can truly state that he will leave behind much to remember. From his “antics with fashion” — recycled out of garbage and found materials — which were used to make garments, and his work crossing over into fashion and performance in GAGAWAKA: Making Strange (2011) and Postmortem (2013), to his re-take with TRASH (2008), an installed urbanscape of garbage, digital photomontages, and three videos: Tracking (2003-04), The Brief Ascent of Marian Hussain (2005), and Turning (2008), Sundaram’s legacy will be remembered for its creativity and boundary-pushing.

Sundaram will also be remembered for his project on the artist Ramkinkar Baij, titled 409 Ramkinkars, which he co-authored with theatre directors Anuradha Kapur and Santanu Bose in 2015.

Also read: How SH Raza and Progressive Artists’ Group put India on international art map

“To say Vivan took risks is an understatement. When you look at his practice, there is a deep reverence for art history, but at the same time, he feels unburdened, addressing his issues with acute directness. Yet, he was interested in his audience completing his work,” says Gandhy, reminiscing about her experiences with him. “In Vivan’s vast body of work, two pieces have deeply impacted me — 12 Bed Ward and Memorial. 12 Bed Ward was created with old shoes, string, wire, and dimly lit light bulbs hanging from the ceiling. The room felt more poignant than eerie, evoking themes of disposability, reuse, and salvage,” she reflects.

“The other piece of work, which was particularly poignant in terms of its impact, was Memorial. The central photograph was of a man who had been killed, and was lying bent in the middle of the road. Vivian’s artwork achieved what great art does best: it left an indelible impression of a moment in history. It etched deeply into our minds and hearts the events of the Bombay riots,” says Gandhy.

Sundaram’s passing is a loss not only for those who admired his work but also for those who looked up to him as a role model and mentor. As a member of a generation of politically engaged artists who sought to use their art to effect social change, Sundaram was unafraid to take on controversial subjects and to use his art as a platform for critique and commentary. His legacy is a reminder of the important role that artists can play in shaping public discourse and challenging the status quo.