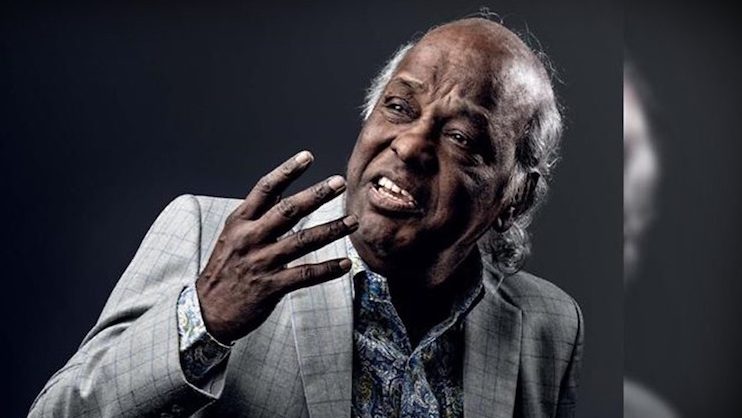

Rahat Indori: Rebel who reminded us India belongs to everyone

Sabhi ka khoon shamil hai yahan ki mitti main,

Kisi ke baap ka Hindustan thori hai…

Four decades ago, when Rahat Indori wrote these angry yet prophetic lines, he scarcely imagined they would one day become an anthem for a generation of Indians fighting a perversion of the idea of nationhood.

“I had forgotten these couplets after reciting them in mushairas (gathering of poets) in the 90s and the 80s,” Indori was to recall at a place called Khargone during one of his last public appearances before his death on Tuesday, August 11, because of Covid-19. But, the lines were destined to become immortal.

Around five years ago, an ugly binary was being imposed on India. Buoyed by the electoral victory of their idol Narendra Modi, the Indian rightwing had unleashed something similar to an ideological purge with a diabolical narrative: those who supported the government’s majoritarian agenda, muscular nationalism and condoned the crimes of cow vigilantes on the rampage across India were the real patriots; those who didn’t were, well, anti-nationals to be packed off to Pakistan.

As the rowdy rightwing raised the decibel level on TV, social media and other public platforms, it resorted to the classic chicanery of taking refuge in symbolic patriotism by appropriating chants of ‘Bharat Mata ki Jai’ and the tricolour for their agenda.

Out of nowhere, Indori’s lines serendipitously began to echo as the fitting counterpoint to these slogans. On TV debates, on social media and at gatherings of Indians keen to reclaim the idea of India from the slogan-shouting, tricolour waiving pseudo nationalists, two poetic lines shut down the rightwing: kisi ke baap ka Hindustan thori hai (India doesn’t belong to a few, everybody has contributed to the nation with their blood and sweat).

Four years later, Faiz Ahmed Faiz and his ‘Hum Dekhenge’ was to become the anthem of another round of civil resistance to the Modi government’s Citizenship Amendment Act. But, by then Indori and his poetry had been guaranteed immortality in every narration of the Modi government’s first tryst with a rebellious, argumentative India.

Rahat Indori’s greatest contribution to poetry, ironically, was his biggest regret. And in this dichotomy lies the story of two Indias—one that loved this rebellious, irreverent, romantic and sometimes naughty shair; and the other that was petty and bigoted enough to divide art with the scalpel of religion.

Indori, who died in the city that will be forever identified with him, underlined this cruel divide at one of his last mushairas (gathering of poets) on February 17 this year. The mushaira was being held in the backdrop of nationwide protests against amendments in Indian citizenship laws and threats of a national register of citizens. In many parts of the country, hundreds of men and women were hitting the streets to rally the country against a law that was seen primarily a draconian act to terrorise and harass Indian Muslims.

On that February night, in a place called Khargone, you could feel Indori’s pain in every line he recited. He started by asking a poignant question:

“Hume pehchante ho?

Hume Hindustan kehte hain,

Magar kuch log jaane kyun

Hume mehmaan kehte hain?

(Do you recognise us?

We are called Hindustan,

But we don’t know why

Some people call us guests)

Then, he continued, voicing the angst of a large number of people whose loyalties have been questioned: “In some videos going viral, I have been called a jihadi. But Allah has told me, I am not jihadi but unique.” Then he read another brilliant couplet:

“Main mar jaun toh meri alag pehchaan likh dena

Lahoo se meri peshani par Hindustan likh dena

(When I die, mention my unique identity,

On my forehead inscribe Hindustan in blood)

Then, on popular demand, he came to his immortal lines, the one that will forever define him. “It pains me when people think this couplet is the couplet of a Muslim poet. When I had written it some forty years ago, it was meant to convey the passion of every Indian. But, sadly, the times have changed.” By the time he read the first line of his couplet, the Khargone sky was resonating with chants of “kisi ke…”

For his fans, Indori, whose father pulled a rickshaw after migrating to Indore from the adjoin town of Dewas, was neither a jihadi nor a Muslim poet. He was the god of 21st century shairi, a star so bright that every time he rose to read his poetry, he was greeted with a roar reserved for Indian cricketers (imagine Sachin-Sachin) and Brazilian footballers.

Indori would recite sher (couplet) after couplet, interspersing them with jokes and witty repartees, taking his audience on a magical journey. Like a magician, he would pull out many persons from his oeuvre—sometimes he would become a rebel, sometimes a philosopher, sometimes a romantic and sometimes a naughty teenager couching madcap lines in poetic metre and delivering them with a wink and a suggestive smile. On his day, Indori would take the audience on a rollercoaster: he made their blood boil, he made them pensive, he made them blush, he made them smile, and he often made them cry.

But, Indori wasn’t just a poet. He was a complete performer blessed with the art of mesmerising the audience with his mannerisms, diction and delivery—someone with a different andaz-e-bayan (style of rendition). Often his poetry would start with a whisper that would silence the audience and end on a high note that shattered the silence, as if it had been scored to the rhythm of an Andrew Rieu concert in Vienna.

Indori was a master of voice modulation, switching from a silken soft to a baritone. Such was the throw of his voice that you could have easily heard him a good 100 metres away without a microphone, on top of a screaming, clapping audience. To this he would add the drama of his body. To the rhythm and cadences of his voice, almost on cue, he would throw his hands towards the sky, thump the lectern and turn his eyes flaming red with passion.

Rahat Indori is no more. But his shayari will continue to inspire millions and, perhaps, a few more revolutions. And those who had the privilege of hearing him live would one day quote Firaq Gorakhpuri to say, “Generations to come would envy you for the fact that you had the privilege of seeing him in person.”

And the rest of us would, of course, keep reminding everyone with a divisive agenda that India “kisi ke baap ka…”