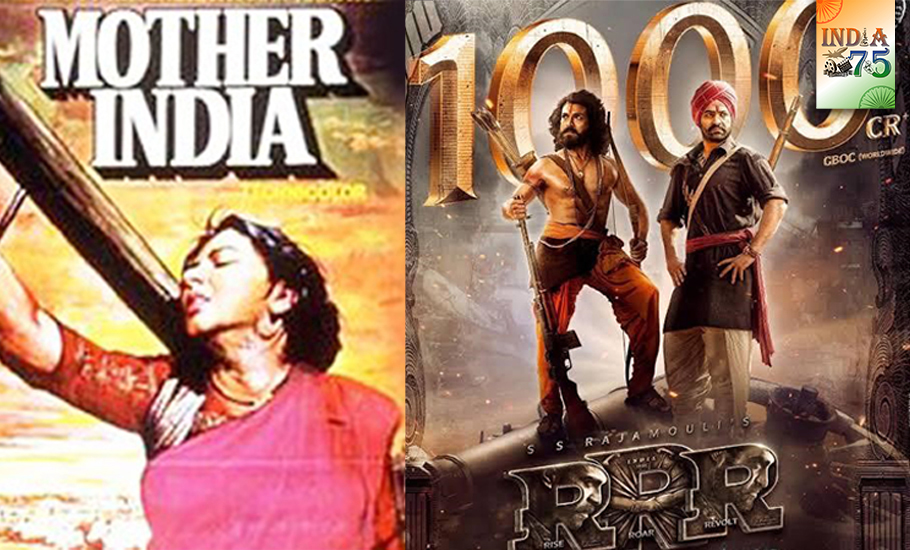

Mother India to RRR, changing texture and political hues of 'patriotic' films

Over the next 25 years, conflict will be between pan Indian Hindu nationalism and regional loyalties; that the two are evenly matched is suggested by South Indian entertainment gaining ground

If every instance of the art has a constituency – a community of like-minded people it addresses – popular art then talks to constituencies large enough to be described as ‘publics’. In cinema, the publics are often national, and popular cinemas therefore exhibit national characteristics wherever the sense of nationhood is strong.

The US and Canada, which are neighbours, may seem similar but the American sense of nationhood is much stronger. Hollywood films exhibit ‘patriotic’ sentiments more conspicuously and the nation is much more strongly inscribed in them. Superheroes wearing blue and red suits – the colours of the flag – are a symptom of this patriotism.

In India, too, after 1947, cinema has tended to be mindful of national concerns. There are, however, different categories of cinema in India. Regional language cinema concurrently addresses a public with local identities and those belonging to the nation – and the two identities can sometimes come into conflict.

In Mani Ratnam’s Tamil film Roja (1992), patriotic sentiments ride on the male protagonist who risks his life quenching the fire on a burning Indian flag, while the heroine collars Hindi-speaking Indian soldiers and screams in Tamil when her kidnapped husband is not rescued. Her insinuation is that someone speaking Tamil does not have much in common with Hindi speakers and that her husband risked his life for ‘them’.

Evidently, this connotation is lost when the whole film is dubbed in Hindi.

We can, therefore, look only at mainstream Hindi cinema for wholehearted portrayals of patriotism since it is pan Indian with a sizable national public. Of course, there is now a regional language, urban-based cinema easily remade in other languages that is also national. A Telugu director’s film Major, for instance, has been simultaneously made in several languages.

Also read: World’s first science-Sanskrit film on Mangalyaan to premier in August

While mainstream Hindi cinema reflected pan Indian concerns even in the colonial era by dealing with ‘reformist’ issues in the 1930s and 1940s. like women’s emancipation (Duniya Na Mane, 1937), it became explicitly nationalist only after 1947. Among the first of these films is Mother India (1956). Nationalism or patriotism (I am not making a distinction) can either be directed inwards or outwards and Mehboob’s film, although the remake of Aurat (1940), introduces a framing sequence situated in the present at the site of an irrigation project, where the heroine recalls the sacrifices of the past.

There are few ‘nationalist’ films from the 1950s – extolling the nation – since what was important was yet to come.

Only with the debacle of the Sino-Indian War – which produced escapism like Waqt (1965) by and large – did nationalism/patriotism make its presence felt in Haqeeqat (1964), which was more like a lament at what had happened.

The hero and heroine die fighting the Chinese, holding hands in the climax of the film. The war with Pakistan in 1965 was more successful for India and Manoj Kumar’s Upkar (1967) was appropriately triumphalist. It is important that the film – once considered the high point of patriotic cinema – deals with several issues together, including family and agrarian ones, and even allegorises Partition, when the misled younger brother demands his share of the family land. And, the war is only one thread.

Indira Gandhi’s period in Indian film history was marked by social conflict since she took a polemical socialist position against the wealthy and there was little sign of nationalist sentiments until well into the 1990s. The anti-western films of Indira’s period, like Purab Aur Paschim (1970), owe to her anti-western rhetoric (while courting the eastern bloc) and are not nationalist.

With the economic liberalisation of 1991 socialist rhetoric became a thing of the past and the conflict between rich and poor (still seen in Damini, 1993) was abandoned. When social conflict of this kind is disallowed, the only conflict that can be portrayed is with external agencies and this led to the patriotism of 1942: A Love Story, Border and Lagaan. Gadar: Ek Prem Katha (2001) can also be called patriotic for the vitriol it pours on Pakistan.

Also read: With sedition law, not easy to criticise govt today: filmmaker Mansore

Hindutva politics era

While this continues well into the new millennium, the most recent phase begins with the Hindutva era in politics. This is politically marked by the polarisation of the public into two camps. Even anti-Pakistani patriotism – because of its associated pro-Hindu jingoism – is making those not politically aligned uncomfortable, even if the cause it serves is unimpeachable, as in The Kashmir Files (2022).

The film – ostensibly only humanist and decrying ethnic cleansing – covertly suggests that all Kashmiri Pandits are patriotic Indians while Kashmir’s Muslims are entirely for Pakistan.

The new patriotic films like Uri: The Surgical Strike are also without the other narrative threads (families, friendships) still in evidence in Border and Lagaan. It can be argued that the polarisation of the Hindi film narrative along these lines has also led to Bollywood’s decline, and the rise of South Indian cinema as national entertainment.

South Indian films are noisy and chaotic but that also means polyphony absent from patriotic Hindi cinema that plays on one note. South Indian entertainment like KGF 2 is by no means sophisticated but audiences may resent – in the long term – being coerced into specific sentiments like patriotic ones.

The next 25 years

The primary issue in this piece is what may happen in the next 25 years to film entertainment in India in terms of its patriotic appeal. If one examines the new South Indian films making national news, they are the very opposite of patriotic.

RRR is even laughable for its anti-British rhetoric although people like it for its digital action sequences, like the tiger hunt and the protagonists beating the British at dancing. Films like Pushpa (2021) play up caste differences and resistance to state authority. But, 25 years is a long time for a prediction of this kind and judging from what has been said, the shape of film entertainment will depend considerably on the socio-political future of the country.

My own view of the socio-political state of the nation is that it will not return to Nehruvian secularism under a national party – just as the country will not return to Nehruvian socialism – and the conflict will be between pan Indian Hindu nationalism and regional loyalties, although the latter are not well organised at present to represent a political alternative.

Also read: Viewing India’s Good, Bad & Ugly through the Bollywood lens

That the two are more evenly matched than it would seem is suggested by South Indian entertainment gaining ground.

Audience sensibilities

Religious conflict will continue but be ‘managed’ since it helps keep up the public excitement that assists political parties electorally. With growing urbanisation, regional loyalty will also not be as in the past when there were larger gaps between the regional sensibilities.

In time, ‘regional’ may simply mean resistance to the subsuming tendencies of the ‘national’. But I also detect a deterioration in the level of popular cinema – national or regional – due to the lowering of educational standards in the humanities and social sciences.

Technical education is vocation oriented and hardly leads students to develop modern worldviews; and the new films (whether RRR or The Kashmir Files), correspondingly, display impressive technical gloss but offer little evidence of praiseworthy thinking. Any pretence at intelligent cinema will perhaps only come from the OTT platforms meant for the educated few.

Jingoist patriotism can be effective in the short term and draw crowds but people seek a variety of situations in narratives where they can emote differently and with different kinds of stimuli. Patriotic films today tend to reduce the variety in such situations/stimuli with the dominance of the heroic.

The unexpected national success of South Indian films already suggests boredom with ‘national’ as the primary draw. While politics itself may continue to be polarised, explicit political motifs will probably lose ground in mass entertainment. There is also the possibility that popular cinema will dissociate itself from national concerns. Nationalism and patriotism are officially promoted but few people among the public – whatever their political persuasions – are open to the official dictate in entertainment.

(MK Raghavendra is a writer on culture and politics)