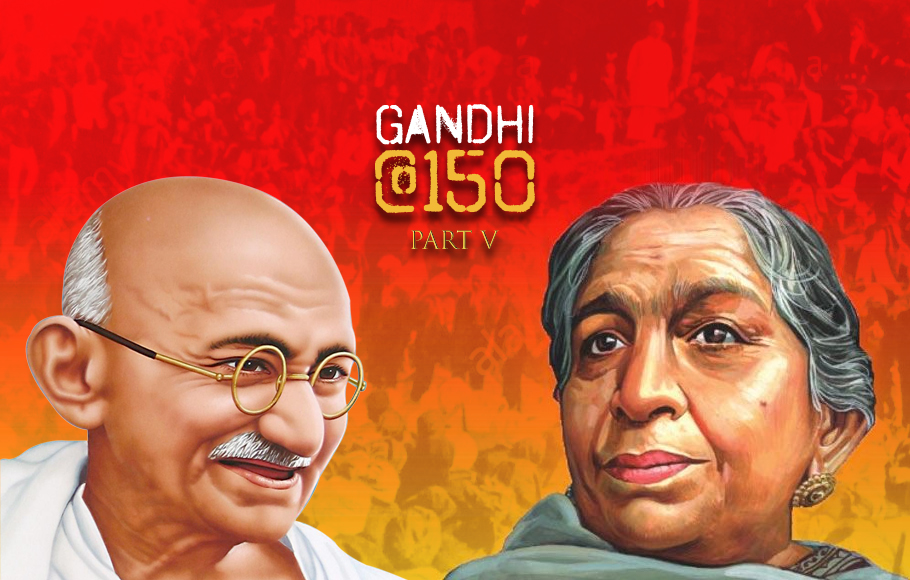

The Nightingale who called Mahatma “Mickey Mouse”

“I went wandering around in search of his lodging in an obscure part of Kensington and climbed up the steep stairs of an old, unfashionable house, to find an open door framing a living picture of a little man with a shaven head seated on the floor on a blank prison blow.

Around him were ranged some battered tine of parched ground-nut and tasteless biscuits of dried plantain flour. I burst instinctively into happy laughter at the amusing and unexpected vision of a famous leader, whose name had already become a household word in our country.

He lifted his eyes and laughed back at me saying: ‘Ah, you must be Mrs. Naidu! Who else dare be so irreverent. ‘Come in, ‘he said, ‘and share my meal’. ‘No thanks. I replied, sniffing, ‘what an abominable mess it is’.”

This was Sarojini Naidu, the poetess from Hyderabad and ‘Nightingale of India’, recalling her first meeting with Mahatma Gandhi in London in 1914.

Thus began a journey of enduring friendship for over three-and-half decades, a friendship that matured with time and influenced each other’s worldview.

She was one of the major influences on Gandhi, particularly on issues of women empowerment. She became one of Gandhi’s key lieutenants in most of his campaigns. She was elected President of the Indian National Congress in 1925, the first Indian woman to occupy the office.

Also read: Former journalist recalls his role in coverage of Gandhi assassination

Sarojini Naidu, poet, feminist and a great orator, was probably the only leader among her contemporaries in the freedom struggle who could tease Mahatma and joke about him. On occasions, she addressed him with nick names like “Chocolate-coloured Mickey Mouse” and “Little Man”, while holding him in utmost reverence.

On several occasions, Gandhi acknowledged the indelible impact that Sarojini Naidu’s reformist ideas had left on him. Mahatma had particularly spoken about how she successfully persuaded the Congress to view women’s emancipation as part of the national struggle for freedom and encouraged women leaders to take the cause of women’s emancipation to the masses.

They shared a special bond, as reflected in the interactions they had on innumerable occasions and their extensive correspondence. Gandhi used to address her as “Mirabai”, “Dear Singer”, “Bulbul-e-Hind”, “Guardian of My Soul” and used to chide her gently for asking him not to fast. There was a great rapport between them based on a deep understanding of each other.

In a moving letter to Naidu on the eve of his fast in 1932, Mahatma wrote:

“It may be that this is my last letter to you. I have always known and treasured your love. I think that I understood you when I first saw you and heard you at the Criterion (in London) in 1914. If I die I shall die in the faith that comrades like you, with whom God has blessed me, will continue the work of the country which is also fully the work of humanity in the same spirit in which it was begun.”

Their scintillating repartees and delightful occasional reproaches were totally free from any trace of malice. Utterly unselfish and transparent, both were endowed with great wit and wisdom.

Struggle for women empowerment

It was Sarojini Naidu’s persuasive skills, prodigious intelligence and indomitable will that convinced Gandhi to make women empowerment an integral part of the freedom movement. She proposed establishment of a women’s section of the Congress to look after the special needs of Indian women. She brought the women’s movement in the country to the centre stage of nationalist politics. She also worked to establish links between the women’s movement in India and international women’s movements.

American historian Geraldine Forbes wrote that Gandhi had initially refused to let women participate in the Dandi March on the grounds that the British would call Indians cowards for “hiding behind women”.

It was on such matters that Sarojini Naidu had arguments with Gandhi and convinced him to change his views.

“You have every right to call upon me to revise my decisions and actions and it is my duty to respond, if I discover the error. And I claim unquestioned ‘obedience’ if I cannot with all the prayerful effort discover any error. You have `manfully’ asserted the right and woman-like offered obedience.

The motherly affection has blinded the poetic vision and prompted you to appeal to my pride to retrace my steps so as to make me cling to life.” Gandhi said in one of his letters to Sarojini Naidu in September, 1932.

She played a key role in planning the Dandi March of 1930. When Gandhi was arrested, she led the march on the Dharsana Salt Works. She was an ambassador of Gandhi and the Indian national movement in her travels at crucial times to South Africa, Britain and the United States.

Also read: In Bengal, everyone wants a piece of Gandhi, but Swaraj is so 1947

Before 1921, Gandhi was against the agitation for female suffrage as a diversion from the main goal of Swaraj while Naidu actively campaigned for acceptance of the principle of female electorates both within Congress (she moved the resolution in support of female suffrage at the 1918 Congress) and in negotiation with the British. Gandhi would later change his mind, embracing the goal of female suffrage as part of Swaraj.

The espousal of causes connected to women’s rights is among the deviations that indicate that Naidu’s ideology was no unthinking following of Gandhi’s.

Despite an unquestionable loyalty to Gandhi, her promotion of his ideas was not so much the wholesale reproduction of Gandhian principles by ‘a celebrity publicist’ but, in Naidu’s own words, ‘the gospel of the Mystic Spinner as interpreted by a Wandering Singer’.

Hindu-Muslim unity

Raised in Hyderabad, the confluence of Hindu-Muslim syncretic culture, Naidu’s commitment to national unity was not just a strategic position but representative of a deeply held cosmopolitan worldview that can be traced to Naidu’s upbringing and early experiences.

Gandhi and the Congress asked her to mediate discussions to heal the developing breach between Congress and the Muslim League in the late 1920s when Mohammad Ali Jinnah broke with Congress.

Again, after independence, Naidu was reluctant when Jawaharlal Nehru offered her the post of Governor of Uttar Pradesh, but Gandhi persuaded her, saying that India needed her long experience in working for Hindu-Muslim unity as Governor of a state where Hindu and Muslim traditions had mixed for several centuries.

She was again called upon to wear the “crown of thorns”, as Gandhi described the Congress Presidentship, over the stormy the Congress session at Calcutta in 1938.

The promotion of Hindu-Muslim unity was a defining theme of Naidu’s nationalist intervention and one that illustrates her unique contribution. Although communal unity was also a key theme for Gandhi, Naidu was devoted to the cause independently and profoundly. She would frequently allude to her upbringing in Hyderabad, ‘the great city which is the true centre of Hindu-Muslim unity and brotherhood.’

Gandhi himself not only recognised Naidu’s importance to the cause of communal unity, but relied on her as a peacemaker. In an article entitled ‘Sarojini, the Singer’, published in Young India in 1924, he issued a public acknowledgement of her role:

“I believe that I can contribute my humble share in the promotion of Hindu-Muslim unity, in many respects she can do much better. She has access to their hearts, which I cannot pretend to.”

Irreverent critic

Sarojini Naidu’s support to Gandhi’s political philosophy was never uncritical or complete. For instance, she did not concur with the aesthetic aspects of Gandhian philosophy as Gandhi himself remarked: “She may deliver an impressive speech on simplicity and voluntary suffering and immediately afterwards do full justice to a sumptuous feast.”

She defied his call to the followers to dress in coarse khadi, “the livery of freedom”, choosing to dress in vibrant south Indian silks. On Mahatma’s life as an ascetic, the poetess had famously joked, “It cost the nation a fortune to keep Gandhi living in poverty.”

Naidu poked fun at ashram food—“boiled unsalted cereals, dog’s food as I called it, only my dogs would never eat such dreadful stuff’

Despite her admiration for Gandhi, she dreaded his diet. “Good heavens, all that grass and goat milk. Never, never, never!”