Why axing Agha Shahid Ali’s poems from Kashmir varsities won’t erase his literary legacy

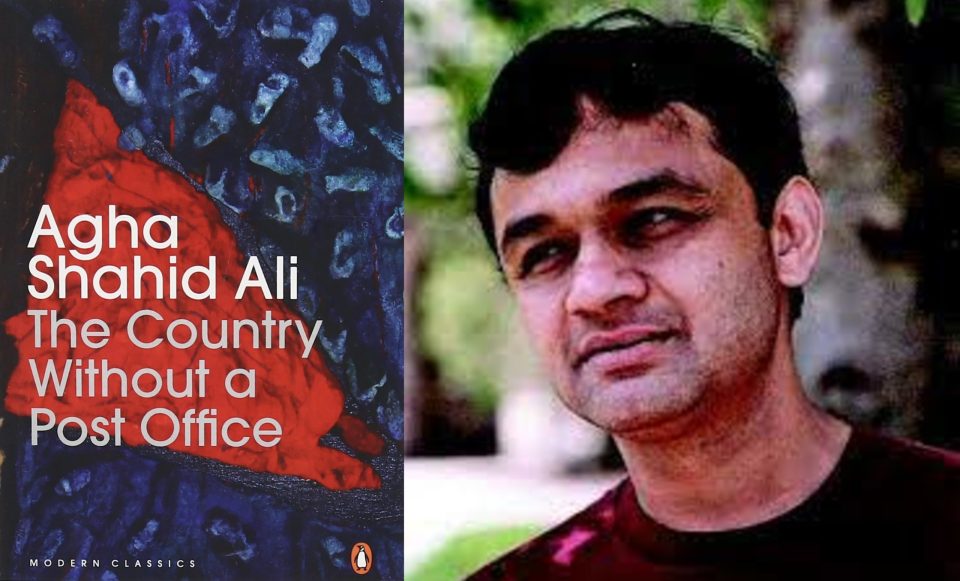

“‘Don’t tell my father I have died,’ he says, and I follow him through blood on the road and hundreds of pairs of shoes the mourners left behind, as they ran from the funeral, victims of the firing. From windows we hear grieving mothers, and snow begins to fall on us, like ash. Black on edges of flames, it cannot extinguish the neighbourhoods, the homes set ablaze by midnight soldiers. Kashmir is burning…” writes celebrated Kashmiri-American poet Agha Shahid Ali (1949-2001) in ‘I See Kashmir from New Delhi at Midnight,’ a poem that figures early in The Country Without A Post Office, his third collection of poetry, which was published in 1997.

The poem has recently been dropped from the post-graduate English curriculum of Kashmir University and Cluster University (Srinagar), along with three of Ali’s other poems: ‘Postcard from Kashmir’, ‘The Last Saffron,’ and ‘Call Me Ishmael Tonight.’ Journalist Basharat Peer’s acclaimed memoir, Curfewed Night (2008), which gets its title from the poem, too, was unceremoniously purged.

No explanation was offered, but you and I can connect the dots and conclude that it is only in line with what the Centre has been up to in recent years: removing any trace of material that doesn’t suit its devious agenda. The recent deletions of chapters on Mughals and Delhi Sultanate from the National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) syllabus, for instance, is a step in the same direction.

Also read: Debasmita Dasgupta’s graphic novel Terminal 3 strikes a note of hope for Kashmiris

Similarly, Urdu poet Allama Iqbal, whose 1904 Tarana-e-Hind — ‘Saare jahaan se accha Hindostan hamara hamara/ Hum bulbule hain is ki/ye gulsitan hamara hamara (Better than the entire world, is our Hindustan/We are its nightingales, and it (is) our garden abode) — became an anthem of opposition against the British Raj, was removed from the political science curriculum of Delhi University in June this year.

Earlier, excerpts of two poems of Faiz Ahmed Faiz were excluded from the Class 10 Social Science textbook in the curriculum of the Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE). These omissions, like shadows cast upon the light, echo a larger tale of a cultural heritage under siege. There should be little doubt that these acts of silencing have to do with the politics of exclusion, which has made its mission to excise everything that is remotely unpalatable to the regime.

Resistance and literature

With its recent decision, the J&K administration, with a decree veiled in the cloak of a new education policy, has attempted to blot out the voice of a poet who turned the ache of the Valley’s troubled history into verses, in the cadence of which throbs the heartbeat of a people caught in the crossfire of violence. Ali’s poems, one can argue, are repositories of Kashmir’s collective memory, and the receptacles of the agony and anguish of Kashmiris.

The advisors on education, however, have branded his songs of pain as ‘resistance literature’ that may fuel minds with dangerous thoughts of secession and aspiration. In doing so, the administration appears to be attempting to rewrite the narrative of Kashmir’s history, suppressing the poetry that chronicled the ground realities of the region. By dismissing Ali’s poetry as fuel for dangerous ideas, they are disregarding the significance of art and literature in addressing — and healing — the wounds of a society; it can only be seen as a bid to erase an essential part of Kashmir’s cultural and emotional identity.

Even if you were to read ‘I See Kashmir from New Delhi at Midnight’ cursorily, you will observe that it is a lament for the countless lives lost and the tremendous suffering endured by the people of Kashmir due to the conflict. Ali begins the poem with a hat tip to WB Yeats: “Now and in time to be/Wherever green is worn, … A terrible beauty is born.”

It encapsulates the paradoxical nature of the region’s struggle, where amidst immense devastation, there remains an enduring sense of resilience. The poem begins with an evocative image: “One must wear jewelled ice in dry plains to will the distant mountains to glass.” This imagery paints a picture of a barren, desolate land where the poet, seeking clarity and connection, attempts to transform the mountains, a symbol of strength and permanence, into glass — a fragile and transparent medium.

Also read: Shame, poverty, myths: A tale of Kashmir’s tribal cloth used by menstruating women

At the heart of the poem is a heart-wrenching encounter between the poet and someone named Rizwan, the son of Molvi Abdul Hai, who crossed over the border during the insurgency in the 1990s and met a tragic fate. Rizwan’s plea, ‘Don’t tell my father I have died,’ hints at the harrowing reality of unexplained disappearances and unaccounted deaths in Kashmir, leaving in its wake a trail of trauma for families and loved ones — a pain made even more unbearable by the uncertainty surrounding the fate of the missing. The restrictions and curfew, enforced by the authorities, shroud the city in darkness, leading to fearsome consequences for those who challenge the oppressive conditions: “The city from where no news can come is now so visible in its curfewed night that the worst is precise.”

A bridge that connects Kashmiri diaspora to their homeland

It would not be an exaggeration to say that Ali’s words transcend time and space, binding together the scattered souls of the Kashmiri diaspora. His poetry becomes a bridge that connects those far away from their homeland to the land they hold in their hearts. He is the voice that laments the loss of a paradise tainted by strife, yet he is also someone who gives solace to the bruised beings in the Valley and beyond. Through his words, he dreams of a future where the fragrance of saffron is not marred by the scent of gunpowder, where the cries of joy replace the echoes of gunfire.

To Kashmir, Agha Shahid Ali is more than a poet. His poetry embodies the spirit of a land that continues to endure, to resist, and to hope. To his admirers, his works serve as a sanctuary, a refuge where they find the strength to cope with the turmoil and the little and big tragedies unfolding around them. In ‘Postcard from Kashmir,’ we hear a lament of exile and a yearning for the lost homeland.

If ‘The Last Saffron’ is a reflection on the fragility of Kashmir’s cultural ethos, ‘In Arabic’ delves into the complexities of language and its power to connect and separate. In ‘Call Me Ishmael Tonight,’ a poignant ghazal dripping with emotion, Ali tries to locate himself in the realm of religion and the conflict in Kashmir. The poem also refers to the destruction of some Hindu temples in the Valley when the conflict broke out.

The pursuit of truth

Literature is meant to stir the soul, to kindle flames of empathy and understanding. Poets, through their verses, navigate the realms of the human condition, offering comfort to the broken-hearted, courage to the downtrodden, and inspiration to the masses. Their words have the potency to unite fragmented societies, to challenge oppressive regimes, and to ignite the spark of revolution. Poets dare to dream, to question, and to challenge the status quo, for their commitment lies not with the fleeting winds of power but with the eternal pursuit of truth and beauty.

From Rumi’s mystic verses to Tagore’s evocative songs, from Maya Angelou’s empowering anthems to Pablo Neruda’s impassioned odes, poets’ words live forever. They can’t be silenced because they are the messengers of the heart; their verses reverberate in the minds of those who read them, across borders and generations, reminding us that the human spirit is limitless and that the pursuit of truth will always find a way to break free. Agha Shahid Ali’s verses may have been removed from the curriculum, but as long as there are those who remember, those who carry the flame of his verses, the story of Kashmir he chronicled will live on — etched not just in books of poetry but in the very heart of the literary community around the world.