What ho! With PG Wodehouse’s sensitivity makeover, we’ve gone too far in censoring classics

Why must we scrub and cleanse literature of any semblance of controversy until it is rendered vapid and insipid?

The publisher of P.G. Wodehouse’s wildly popular Jeeves and Wooster series, Penguin Random House (PRH), has taken it upon themselves to play the literary equivalents of plastic surgeons and alter the “unacceptable prose” of one of the greatest humorists of the 20th century.

Apparently, they found the language of Wodehouse’s Thank you, Jeeves (1934) — the first full-length novel to feature the two characters — too “outdated” for the modern-day sensitivity readers. So, they decided to make some “minimal” edits to better reflect current sensibilities.

If you pick this year’s edition of Thank you, Jeeves, a disclaimer, a trigger warning will greet you on the opening pages: “Please be aware that this book was published in the 1930s and contains language, themes and characterizations which you may find outdated. In the present edition we have sought to edit, minimally, words that we regard as unacceptable to present-day readers.”

Also read: Harry Potter, 15 years on: From frenzied anticipation to franchise fatigue

It was necessary, you see, because the good folks at PRH did not want us to be caught off guard by Wodehouse’s shocking and insensitive phrases — racial slurs, et al. Thankfully, we can now all rest easy knowing that the publisher has our best interests at heart and is protecting us from the horrors of the past, and the atrocities of language. Or, to be more precise, from the prejudices and problematic worldview of our literary heroes of the yore, whose works we have revelled in, without so much as raising an eyebrow, for several decades.

Let’s shield ourselves from books

You have got to give it to PRH and their ilk: a few weeks back, it was HarperCollins which made changes to Agatha Christie’s books, removing references to Jews and other minorities that were deemed offensive by sensitivity readers. It’s truly remarkable how considerate they have been of the feelings of sensitivity readers, who transform into ultra-conscious creatures when it comes to consuming culture. One wrong word or insinuation here or there, and it’s like a bomb goes off in their heads.

So what if we’re living in a world where you can’t walk down the street or scroll down your social media handles without being bombarded with graphic images, disturbing news, horrifying coinages: murders, rapes, riots, trolling, atrocities against the marginalised, including people of colour and LGBTQI+. It’s the books that we need to shield ourselves from.

Also read: ‘Beef’ review: A darkly humorous exploration of road-rage-fuelled feud, repressed grief

We learn from literature and litterateurs that life is not meant to be lived in the safety of the familiar, but rather in the wild, untamed expanse of the unknown. Books, we have been told, have the power to expose us to new ideas, to challenge our assumptions, and to push us out of our comfort zones. But if the publishers of such varied authors as Roald Dahl, Ian Fleming, Christie and Wodehouse are hell bent on making books a safe haven, they must have a sublime reason in mind.

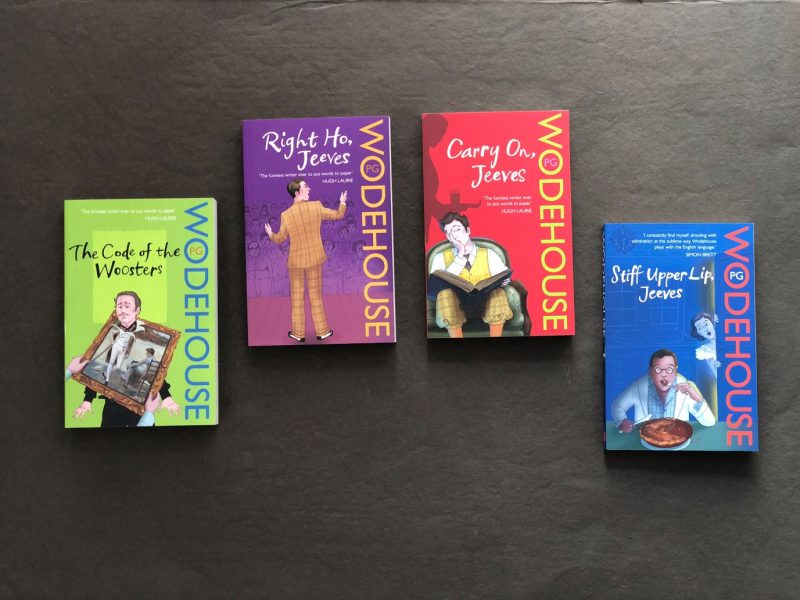

PRH, which has also made changes in Right Ho, Jeeves and Thank You, Jeeves — both written in 1934 — insists that the alterations do not affect the stories in the books. In all these three novels, the publisher has removed or changed numerous racial terms in dialogue and narration, primarily involving the well-meaning but bumbling Bertie Wooster, the quintessential upper-class Englishman, who lives a life of leisure and luxury.

Bertie’s hilarious escapades, and enduring friendship, with his trusty and resourceful valet, Jeeves feature in 35 short stories and 11 novels — each one bursting with the unique blend of humour, wit, and charm that has made Wodehouse one of the most beloved authors of all time.

The Ministry of Hurt Sentiments

As the wheels of the global publishing industry — dominated by giants like PRH and HarperCollins India — spin, and spin some more, they seem to be operating more like the Ministry of Hurt Sentiments, constantly tinkering with texts and excising anything that might cause discomfort or offense. Alas, we’re left with no other option but to endure this literary censorship imposed by the moral police of literature, who seem to be carrying out their duties with reckless abandon. Who will step up and challenge these mighty gatekeepers of the written word?

After the news around Dahl censorship broke, American author Joyce Carol Oates said: “One imagines unpaid interns gleefully censoring prose by renowned/no longer living writers. ‘There, take that! See how it feels.‘” I think about Oates’ response often. It must be some kind of power trip for editors at these publishing houses to gleefully slash out anything that doesn’t conform to their — I daresay — narrow worldview.

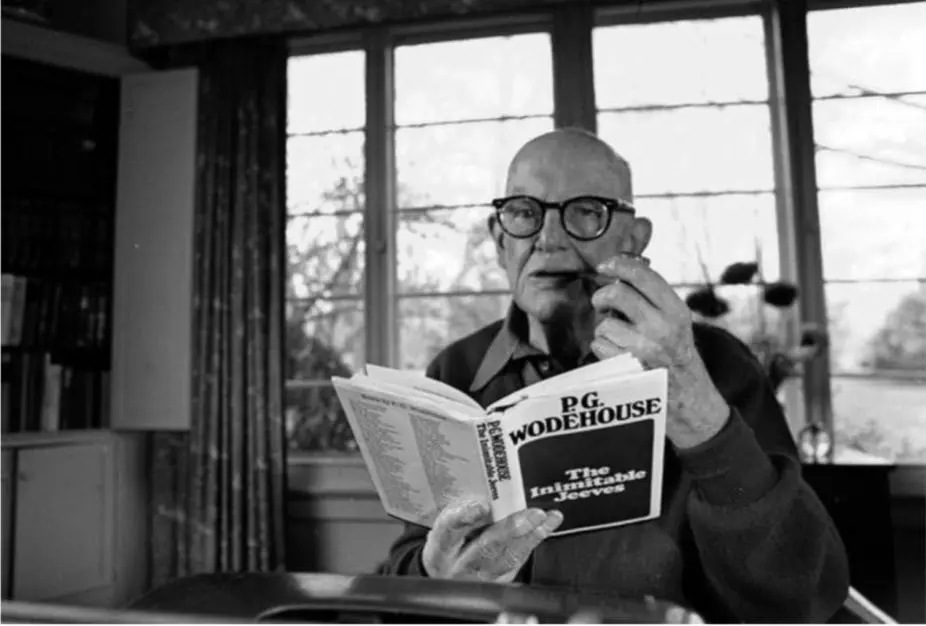

You and I know that these changes are a travesty and that they ruin the original vision of the author. But who cares about that, right? It’s not like Wodehouse was some kind of literary genius or anything even though his oeuvre showcases his astounding literary breadth? Talking of genius, let me tell you a few things about Wodehouse, who wrote nearly 90 books.

It is in the textures of Wodehouse’s sentences that we can see the originality of his mind at work. In his later years, his letters unveiled a love for the works of Honoré de Balzac, Jane Austen, Henry Fielding, Tobias George Smollett, and William Faulkner, a literary breadth that manifested itself throughout his career. Yet, unlike the abstruse erudition found in the works of Ezra Pound or Gertrude Stein, Wodehouse deftly wove together classical references to Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley, Plato and Maurice Maeterlinck with the slang of his time, moving seamlessly between registers, both celebrating and diminishing the world of high art, as a critic wrote once.

Humour, satire, metaphor and simile

Besides humour and satire, it is Wodehouse’s unparalleled mastery of metaphor and simile that truly sets him apart. Each turn of phrase in his novels dazzles with its inventiveness, from “ice formed on the butler’s upper slopes” to a man who “wilts like a salted snail.” In one letter to a friend, he compares the stirring of things to the circulation of blood in a frozen Alpine traveller who has received a shot of brandy from a St. Bernard dog. And upon his return to New York, he humorously notes that it was like reuniting with an old sweetheart who had put on a few extra pounds.

Some of Wodehouse’s metaphors and similes border on the absurd, yet they are always crafted with a sense of playfulness and whimsy. For him, style was a carefully crafted form of release, a means of breaking free from the constraints of convention and revelling in the sheer joy of language.

Though Wodehouse lived through tumultuous times, he remained somewhat detached from the major political events of the 20th century. His writing hardly contains any discernible political undertones. Because of this, his critics have grappled with how to approach a literary corpus that seems so deliberately removed from political discourse. Wodehouse himself claimed that his method of novel-writing involved fashioning a “frankly fairy story” and disregarding the demands of real life altogether, as he notes in one letter.

When reading about the eccentric characters that populate Wodehouse’s novels, as Evelyn Waugh astutely observes, we are not preoccupied with the economic implications of their social standing, nor are we skeptical about their improbable celibacy. We do not expect them to age, as if they were the Forsytes or the Three Musketeers.

We are not concerned with how they might respond to shifting social conditions, as some publishers’ blurbs might suggest we should be with other literary sagas. Wars do not disturb them, and they remain impervious to the passage of time. They exist in a timeless world that cannot become dated because it has never existed in the first place. The only maladies that afflict them are occasional hangovers, as they live out their days in a state of blissful ignorance, seemingly oblivious to the outside world.

But I digress. Despite all these pointers to Wodehouse’s rich legacy, however, we can just change his books to suit our tastes, no problem. In fact, why stop there? Let’s just go ahead and change every classic book ever written. Let’s take out all the offensive language, all the outdated ideas, all the controversial themes and references.

Let’s sanitize everything until it’s so bland and blah that no one will ever be offended by anything ever again. Let’s scrub and cleanse literature of any semblance of controversy until it is rendered so vapid and insipid that no one will ever be hurt, disturbed, moved, challenged, or provoked by it ever again. After all, what’s the point of embracing literature in all its messy, complicated glory?

Text and context

While reading and writing, you and I have come to understand that all writing is unavoidably tied to the era in which it was created, steeped in the zeitgeist of its time. One cannot simply extract a piece of writing from its surroundings and analyze it in isolation.

Also read: Jeyamohan interview: Ezhaam Ulagam, or The Abyss, is a spiritual inquiry into beggars’ lives

But why bother with such tedious considerations? Why can’t we dispense with the frivolous concept of text and context? If a work of literature doesn’t quite suit our modern sensibilities, why not just ignore the historical context altogether and read it through our present-day lens?

Who needs to be mindful of the time and place in which a story is set when we can simply impose our own perspectives on it? After all, it’s not like historical context has any relevance to how we interpret and understand a work of literature, right?

Dahl’s books are filled with all sorts of disturbing themes — child abuse, murder, animal cruelty — and yet he insists on presenting them in a whimsical, almost playful manner. How insensitive! Thankfully, his publishers have realised that there are children reading his books and sanitized the content to make it more palatable for young minds.

As for the stories by Agatha Christie, the so-called “queen of crime,” they are chock-full of violence, deception, and all sorts of unsavoury behaviour. Clearly, she had no regard for the feelings of her readers, who must be protected at all costs. It’s a good thing her books are being edited to remove any offensive material — who knows what kind of damage could be done otherwise?

And, now, it is the turn of Wodehouse, whose harmless stories about bumbling aristocrats and their antics are not quite harmless. The publishers, therefore, must step in and protect us from ourselves by removing any references to outdated social norms or potentially offensive material, lest someone somewhere be triggered by a passing remark.

While Wodehouse’s publisher is at it, I would beseech them to get rid of Jeeves and Wooster altogether. And not publish them at all. I mean, who needs them? It’s not like they were beloved characters that people have been reading about for decades.

PRH can just replace them with more modern, politically correct characters that better reflect our values. They must take political correctness to a whole new level, where anything that might possibly offend someone is banned faster than you and I can say ‘censorship.’